On November 30, 2025, Yearn Finance's yETH Weighted Stable Pool was exploited for over $9 million [1]. The root causes were unsafe arithmetic in the invariant solver _calc_supply() and a non-disabled bootstrap path that allowed re-entry into initialization logic. The official post-mortem [2] lists five items as root causes; we reclassify them as two defects (the vulnerabilities above) and two architectural preconditions that became exploitable only in the presence of these defects. Other available analyses focus on step-by-step attack transaction details. Between high-level summaries and transaction-level details, a gap remains: why and how did the attack actually work? This post fills that gap, using Foundry and Python simulations to trace how key values evolve step by step and where the calculations break.

This analysis primarily makes the following three contributions:

- Loss breakdown by vulnerability. The two vulnerabilities are not co-dependent: unsafe arithmetic alone caused ~$8.1M in losses (90% of the total), while the bootstrap path enabled an additional ~$0.9M. This clarifies which vulnerability was primary.

- Reclassification of root causes. The official report's five root causes are better understood as two implementation defects (consolidating three of the five items) plus two architectural preconditions that became exploitable only in combination with the defects.

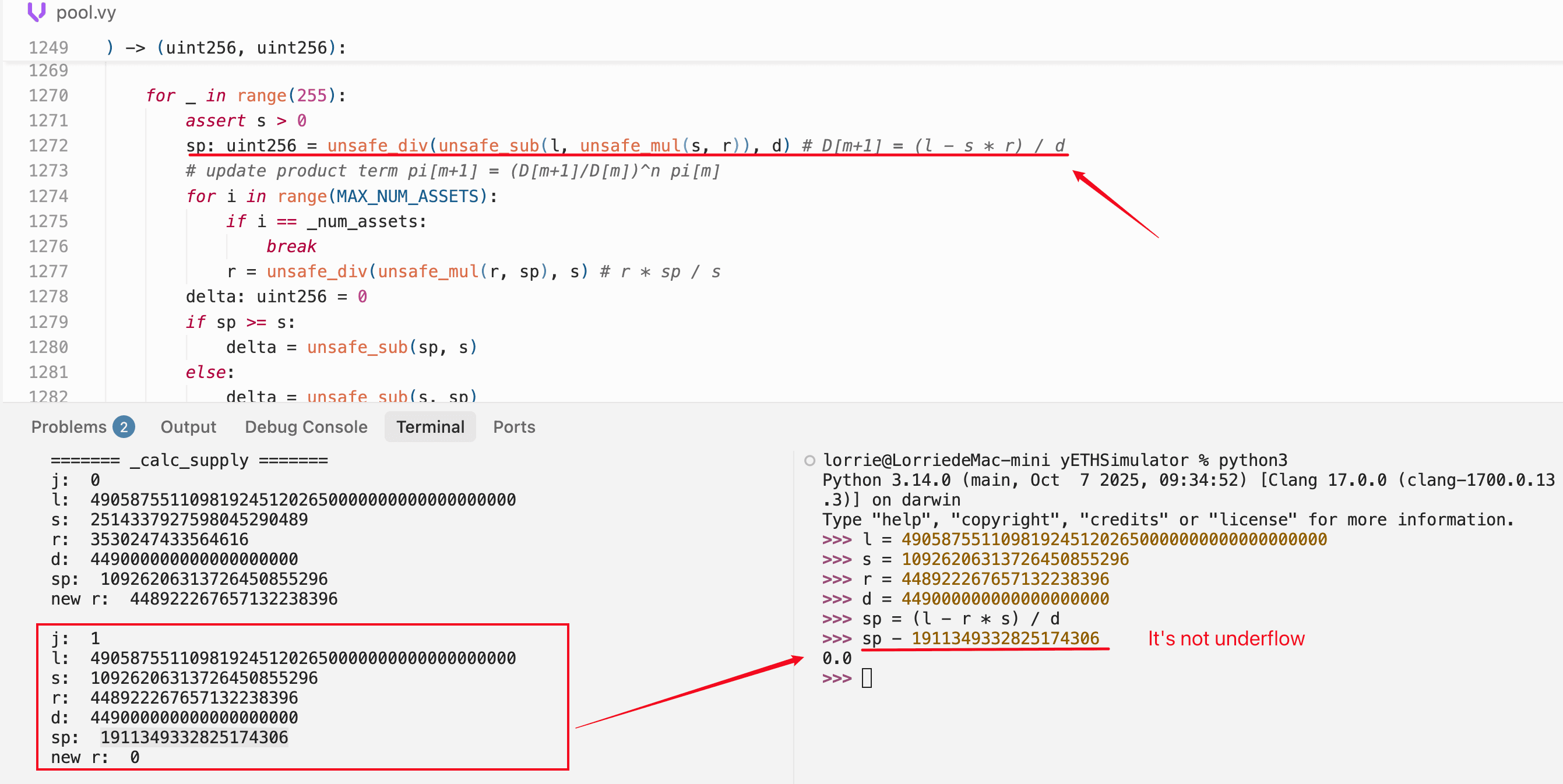

- Correction of technical misunderstandings. The claim that "an underflow in the second iteration zeros the product term" does not hold: our simulations show the product zeros through rounding in division, not underflow, and the profit-generating underflow occurs in a different phase entirely.

The remainder of this post is organized as follows. Section 0x1 provides background on yETH's weighted stable pool and its invariant solver. Section 0x2 analyzes the two root causes and their failure modes. Section 0x3 traces the three-phase attack in detail. Section 0x4 corrects two common misunderstandings with simulation evidence. Section 0x5 concludes with recommendations.

TL;DR

Root causes: Two vulnerabilities were exploited, but with asymmetric impact:

- Unsafe arithmetic in

_calc_supply()(primary, ~$8.1M). The function that recomputes yETH supply from pool state contains two arithmetic failures: rounding-down inunsafe_div()can zero the internal product term, and underflow inunsafe_sub()can wrap an intermediate value to an enormous positive integer. This vulnerability alone was sufficient to drain the yETH weighted stableswap pool. - Non-disabled bootstrap path (secondary, ~$0.9M). The

prev_supply == 0initialization branch was never permanently gated after deployment. After the first vulnerability drained supply to zero, this path became reachable, enabling additional profit from the yETH/WETH Curve pool.

Within the unsafe arithmetic vulnerability, only the rounding-down failure (Failure Mode A) was used in Phase 2; the underflow failure (Failure Mode B) is co-dependent with the bootstrap path and together they enabled Phase 3.

The attacker executed a three-phase sequence:

- Preparation: Skew the pool's asset distribution through repeated add/remove cycles, creating extreme imbalance in virtual balances.

- Supply manipulation: Exploit rounding-down in

_calc_supply()to collapse the product term to zero, then drain total supply to zero through a series of mint/burn operations. All LSTs of the pool were withdrawn and swapped to WETH afterwards, leading to ~$8.1M in losses. - Profit extraction: Trigger the bootstrap path (

prev_supply == 0) with dust deposits, exploiting the underflow in_calc_supply()to mint ~2.35×10⁵⁶ yETH, which were used to drain the yETH/WETH Curve pool, leading to ~$0.9M in losses.

Two common misunderstandings corrected:

- "The invariant breaks because

pow_up()andpow_down()round differently." We verified by replacingpow_up()withpow_down()in a Foundry simulation: the exploit still works. Rounding mismatch is not a root cause. - "An underflow in the second iteration makes an intermediate term collapse to zero." Our Foundry and Python simulations show no underflow occurs in the second iteration. The actual value is ~1.91e19 (not ~1.94e18 as claimed), a legitimate result of a correct subtraction. What zeroes the product is the subsequent rounding-down in the division, not an underflow.

0x1 Background

Two pools lost assets in this incident: the yETH weighted stableswap pool (a Yearn pool holding LSTs, ~$8.1M lost) and the yETH/WETH Curve pool (a Curve stableswap pool, ~$0.9M lost). The yETH weighted stableswap pool is where the core vulnerability lies. This section provides background necessary to understand the vulnerability and exploit.

0x1.1 Virtual Balances and the Invariant

The yETH protocol is an Automated Market Maker (AMM) for Ethereum Liquid Staking Tokens (LSTs) [3]. The affected yETH weighted stableswap pool aggregates multiple LSTs into a single pool: users deposit LSTs and receive yETH as pool share tokens.

Because each LST represents staked ETH that accrues rewards over time, its exchange rate relative to base ETH changes. To unify accounting, the pool defines a virtual balance for each asset: on-chain balance × exchange rate. This normalizes all assets into beacon-chain ETH units. The sum of all virtual balances is denoted .

The pool contains 8 assets (indexed 0–7), each with a designated weight :

The pool's state is governed by a weighted StableSwap-style invariant [4]:

where:

- is the invariant scale, which directly equals the total yETH supply of this pool. When the pool is perfectly balanced, .

- is the weighted product term, defined as , where is the weight of asset i and .

- is the amplification factor, a single protocol parameter (not ). denotes this factor raised to the power , where is the number of assets (8 in this pool). It controls the curve shape between constant-sum (near equilibrium) and constant-product (at extremes).

The key property: does not have a closed-form solution. It must be solved numerically. That solver, _calc_supply(), is where the arithmetic vulnerability lives.

0x1.2 The Invariant Solver

The protocol recomputes through a fixed-point iteration capped at 256 rounds. This algorithm is implemented as _calc_supply() in code (detailed in Section 0x2.1). Each round performs three steps:

Step 1: Update the supply estimate.

Step 2: Update the product term to match the new supply.

Step 3: Check convergence.

If , return ; otherwise repeat from Step 1.

The initial values , , and influence the early iterations; while theoretically irrelevant to final convergence, they affect results in practice due to finite iteration and fixed-precision arithmetic.

The implementation uses fixed-precision integer operations: division rounds down, and subtraction does not guard against underflow. Under normal pool conditions, intermediate values stay within safe ranges. Under extreme pool states, they do not. Section 0x2.1 analyzes these failure modes in detail.

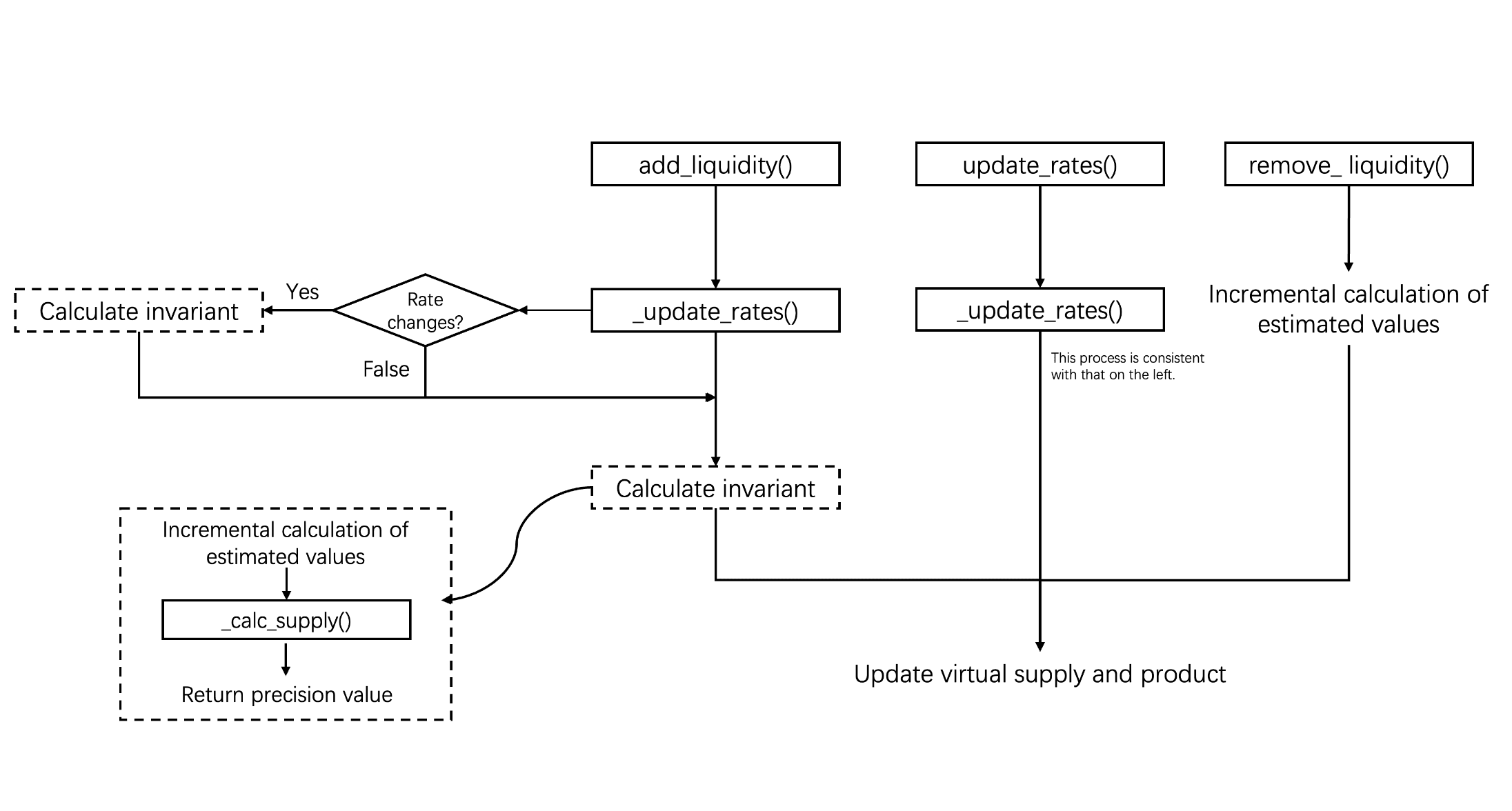

0x1.3 The Three Interfaces and the Invariant Solver

The protocol exposes three entry points that affect pool state by updating the weighted product term (stored as vb_prod in code):

| Interface | What it does | Triggers _calc_supply()? |

|---|---|---|

add_liquidity() |

Deposits assets in arbitrary proportions | Yes |

update_rates() |

Updates external exchange rates | Yes |

remove_liquidity() |

Withdraws assets proportionally by weight | No (uses proportional scaling) |

The asymmetry matters: add_liquidity() allows arbitrary-proportion deposits (it can massively skew the pool), while remove_liquidity() always withdraws proportionally. Repeated cycles of add/remove can therefore ratchet the pool into increasingly unbalanced states.

The Mechanism to Update Rates

As discussed above, virtual balances () are computed based on the exchange rates of LSTs. Hence it is important to understand the way to update rates.

Specifically, add_liquidity() and update_rates() functions can update rates via the internal function _update_rates(), while the remove_liquidity() function does not perform rate synchronization.

add_liquidity()invokes_update_rates()before executing critical operations to ensure that asset exchange rates are synchronized to the latest state.update_rates()allows manual rate updates.

The _update_rates() function checks whether the exchange rates recorded within the contract are consistent with the external rates. If a discrepancy is detected, it triggers a recomputation of the virtual balances and subsequently updates the invariant; otherwise, the update process is skipped.

How Each Interface Handles π

Based on how they affect the invariant, these three functions can be classified into two categories. Specifically, add_liquidity() and update_rates() allow non-proportional changes in the virtual balances, and therefore require iterative recomputation of the supply and the product . In contrast, remove_liquidity() withdraws liquidity proportionally and does not require iterative calculation.

The base formula for computing the product from scratch is:

where is the supply, is the weight of asset , is its virtual balance (stored as vb[i] in code), and n is the number of assets. This form is algebraically equivalent to the definition in Section 0x1.1, with distributed into the product.

add_liquidity()has two paths (code shown in Section 0x2.2):

- Bootstrap path (when

prev_supply == 0): Computesvb_prodfrom scratch using equation (4). This path remaining accessible after deployment is the state management vulnerability discussed in Section 0x2.2. - Normal path (when

prev_supply > 0): The computation process is divided into two steps:-

a) Uses an incremental update based on the ratio of old to new virtual balances:

where and are the virtual balances before and after the deposit.

-

b) Iteratively calibrate the precise value by calling

_calc_supply()with this estimate as input, recomputing the invariant and the exact value of .

-

-

update_rates()is triggered when exchange rates change, causing the virtual balances of the corresponding assets to be updated. Its subsequent computation flow follows the normal path ofadd_liquidity(), i.e., the invariant is recomputed iteratively. In addition, based on the newly calculated supply, the contract mints or burns yETH to ensure that the liquidity supply remains consistent with the updated virtual balance state. -

remove_liquidity()always computesvb_prodfrom scratch using equation (4), after proportionally reducing each virtual balance.

0x2 Root Cause Analysis

Two vulnerabilities were exploited, with different roles and impact. The primary root cause was a computation flaw in the invariant solver _calc_supply(), which had two failure modes: (A) rounding down could zero the product term, degenerating the invariant into a constant-sum model and leading to excess LP minting (supply inflation); and (B) an underflow condition could also inflate supply. Only Failure Mode A was used in Phase 2 (~$8.1M). Failure Mode B was co-dependent on the secondary vulnerability.

The secondary root cause was a state-management defect: the pool’s initialization branch remained reachable. After Phase 2 drove supply to zero, Failure Mode B combined with the bootstrap path to enable an additional ~$0.9M in losses (Phase 3).

0x2.1 Unsafe Arithmetic in `_calc_supply()` (Primary)

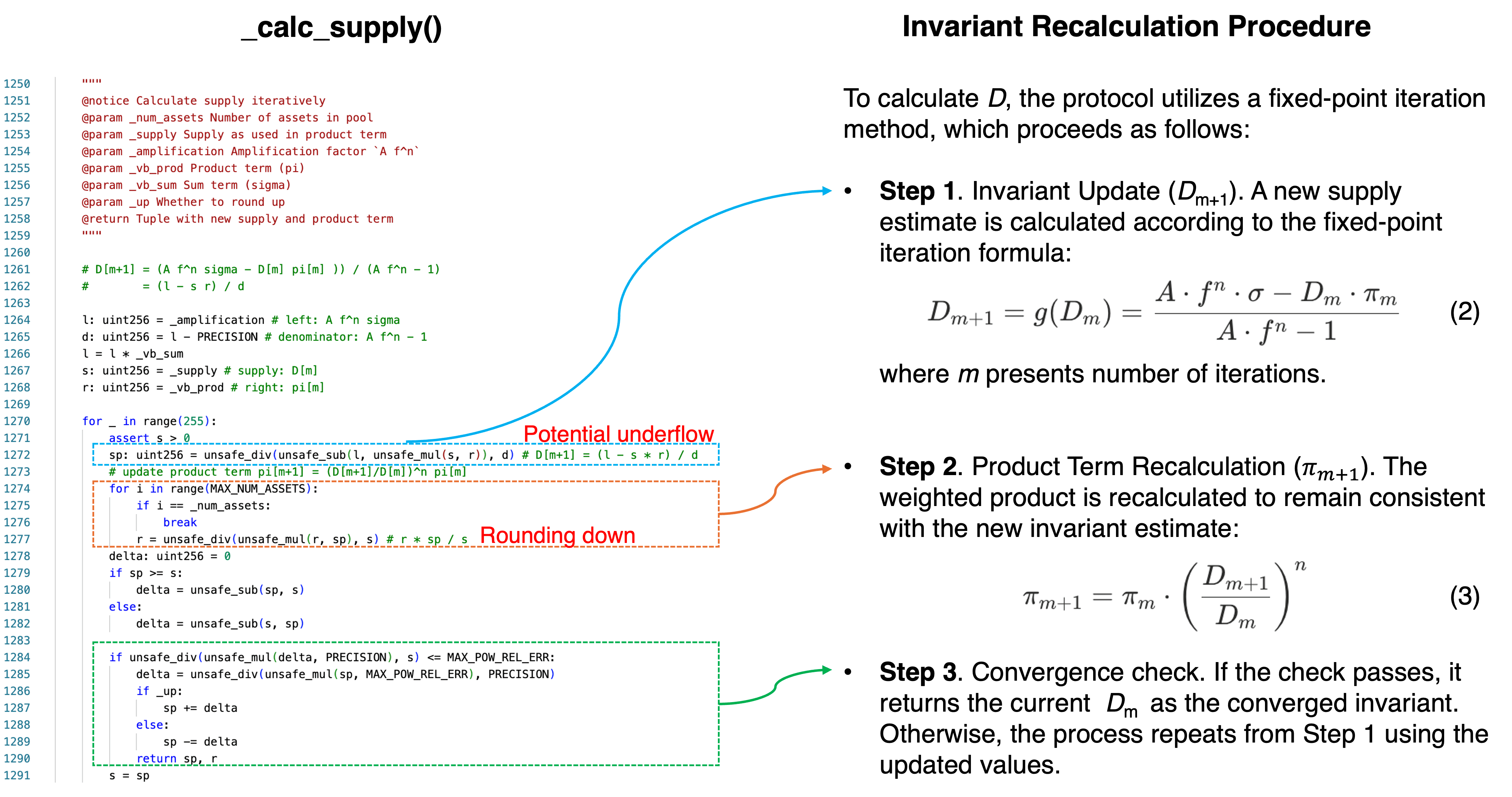

Figure 2 maps the _calc_supply() implementation to the mathematical procedure from Section 0x1.2, annotating the two arithmetic failure sites analyzed below:

The code variables map to mathematical terms as follows:

| Code variable | Mathematical role |

|---|---|

s |

Current supply estimate |

r |

Product term |

sp |

Next supply estimate |

l |

Numerator constant: |

d |

Denominator constant: |

The critical expressions are:

sp = unsafe_div(unsafe_sub(l, unsafe_mul(s, r)), d) # Step 1: D[m+1]

r = unsafe_div(unsafe_mul(r, sp), s) # Step 2: π update (per asset)Two arithmetic failure modes exist inside this function, targeting different lines and producing different effects. Both require the pool to be in an extreme state to trigger.

Under normal conditions, the iteration behaves correctly: l - s * r is a modest positive value, and the iteration converges in a few rounds.

1. Failure Mode A: Rounding-Down Zeros the Product

In Step 2, the product is updated per-asset as:

r = unsafe_div(unsafe_mul(r, sp), s) # r = r * sp / sSince unsafe_div() performs integer division, it always rounds down. When the pool is severely imbalanced and sp is much smaller than s (as happens after a manipulated large deposit), the numerator r * sp can become smaller than the denominator s. Integer division then yields r = 0.

Once r is zero, it stays zero for all subsequent iterations. The product term has permanently collapsed.

A common misattribution claims this failure stems from rounding mismatch between pow_up() and pow_down(). Section 0x4 presents evidence that this is incorrect.

2. Failure Mode B: Underflow Inflates the Supply

In Step 1, the new supply estimate is computed as:

sp = unsafe_div(unsafe_sub(l, unsafe_mul(s, r)), d) # sp = (l - s*r) / dThe subtraction l - s*r in equation 2. Under normal conditions, this is positive. However, when the pool reaches a degenerate state with zero supply, the initialization branch in add_liquidity() (detailed in Section 0x2.2) recomputes the product term from scratch, and the relative magnitudes can invert.

Specifically, when add_liquidity() is called on a zero-supply pool with dust amounts, the initialization branch calls _calc_vb_prod_sum() to compute fresh values using equation (4) (Section 0x1.3). With tiny deposits, vb_sum is minuscule (e.g., 16), but dividing by near-zero balances and raising to high powers amplifies the product to a disproportionately large value (e.g., ~9.13e20). When s * r exceeds l, the subtraction yields a negative mathematical result.

Since unsafe_sub() performs subtraction in unchecked uint256 arithmetic, a negative result wraps around to an enormous positive integer (close to ). This wrapped value propagates through the division and subsequent iterations, producing an absurdly large supply estimate, which the protocol then mints as real yETH tokens.

A common claim asserts that such an underflow occurs in the second iteration of a specific supply manipulation step. Section 0x4 shows this claim is incorrect: the actual underflow that inflates supply occurs in a completely different context (Phase 3 of the attack).

3. How These Failures Enable the Attack

These two failure modes operate in different phases of the exploit, with different profit contributions:

-

Failure Mode A (Phase 2, ~$8.1M): When the attacker deposits into a severely imbalanced pool, the product term zeros out, causing

_calc_supply()to return an inflated supply. The protocol over-mints yETH to the attacker. This failure mode alone, without any involvement of the bootstrap path, enabled the attacker to drain the yETH weighted stableswap pool of its LST assets. -

Failure Mode B (Phase 3, ~$0.9M): After supply has been drained to zero, the bootstrap path recomputes a large product term from dust deposits, causing the subtraction to underflow. The protocol mints an astronomically large amount of yETH, which the attacker uses to drain the separate yETH/WETH Curve pool.

The dependency is one-directional: Failure Mode A is independently exploitable and caused 90% of the losses, while Failure Mode B requires Failure Mode A to first drive supply to zero.

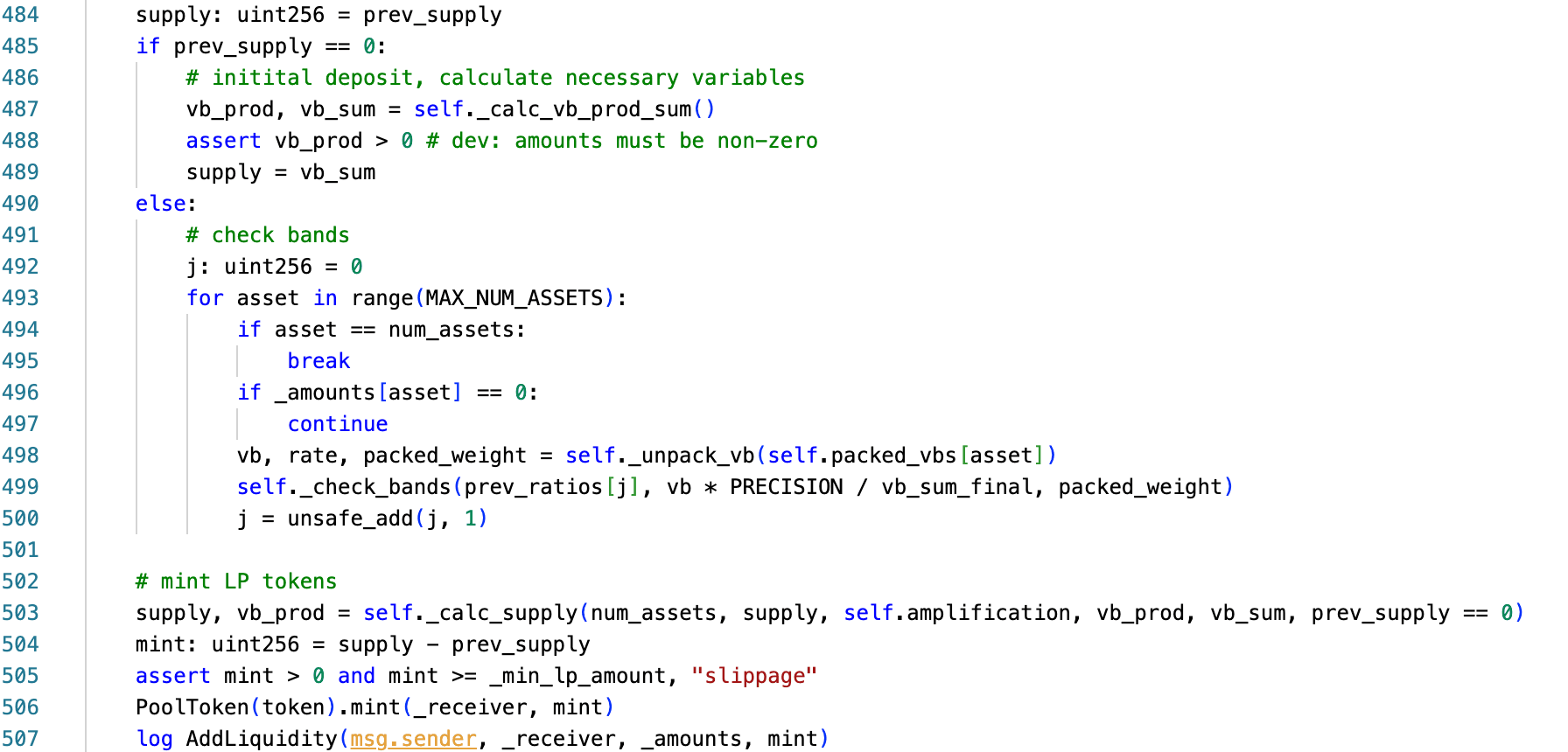

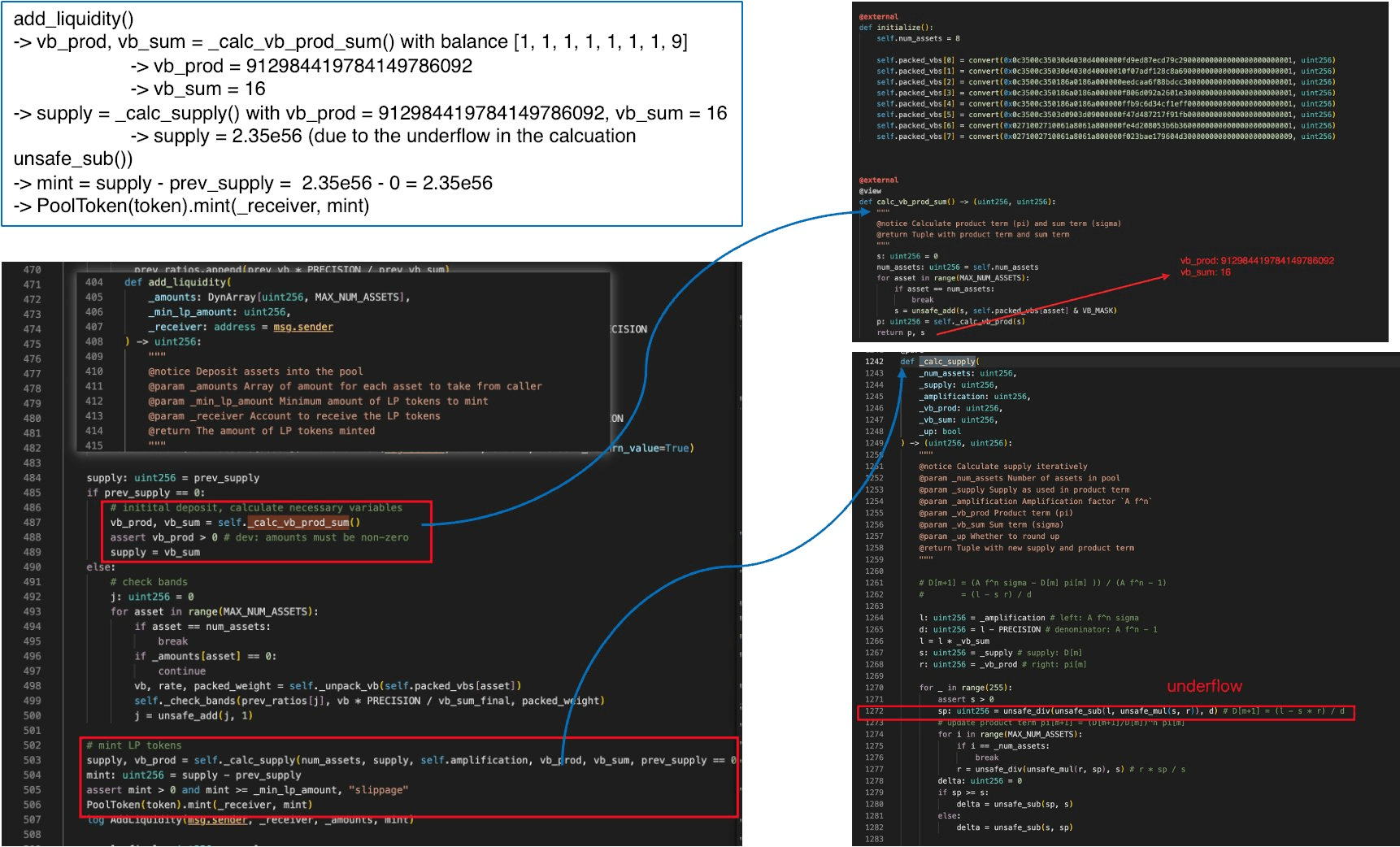

0x2.2 Non-Disabled Bootstrap Path (Secondary)

The add_liquidity() function contains a branch for the pool's initial deposit:

The logic can be abstracted as follows:

if prev_supply == 0:

# Bootstrap path — compute vb_prod and vb_sum from scratch

vb_prod, vb_sum = _calc_vb_prod_sum(balances, rates, weights, ...)

supply = vb_sum

else:

# Normal path — use stored vb_prod, perform incremental checks

...

# Called after both branches, with prev_supply == 0 as a flag

supply, vb_prod = _calc_supply(num_assets, supply, amplification, vb_prod, vb_sum, prev_supply == 0)When prev_supply == 0, the function bypasses stored state and recomputes vb_prod and vb_sum from scratch via _calc_vb_prod_sum(), using equation (4) (Section 0x1.3). This bootstrap branch was intended for one-time use during pool initialization but was never permanently gated after the first deposit.

If total supply can be driven to zero (through any combination of burns and withdrawals), the branch becomes reachable again. An attacker who re-enters this path controls the initial conditions passed to _calc_supply(), potentially triggering the arithmetic failures described above under parameters that would never arise during normal pool operation.

This is a known vulnerability pattern. In August 2023, the Balancer V2 incident similarly depended on driving supply to zero to reset internal rates, enabling the attacker to re-enter initialization logic at artificially favorable parameters [6]. Whether a deployed pool can be driven back to its initial state, and what invariants hold when it does, is a question protocol designers must explicitly address.

0x3 Attack Analysis

The exploit unfolds across a coordinated sequence of the attack transaction [5], organized into three phases. Each phase builds on the state established by the previous one.

0x3.1 Phase 1: Skewing the Pool (Preparation)

Goal: Create extreme imbalance in virtual balances across assets.

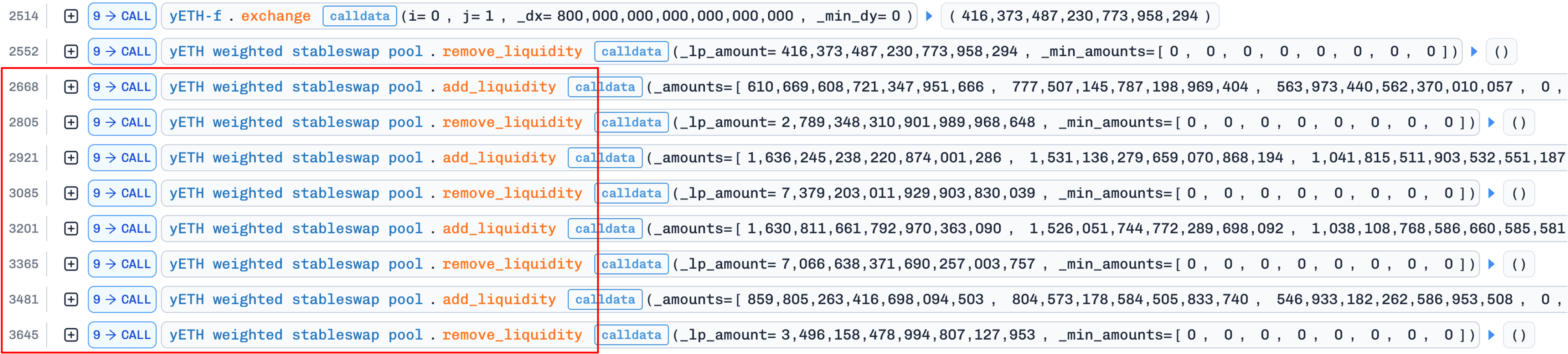

The figure below illustrates the transaction trace for this phase (the flash-loan step is omitted due to space constraints):

The attacker first borrows large amounts of LST assets via flash loans from Balancer and Aave, specifically 5,500e18 wstETH, 3,100e18 WETH, 1,800e18 rETH, 2,000e18 ETHx, and 200e18 cbETH.

Next, the attacker swaps approximately 800e18 WETH for about 416e18 yETH in the yETH/WETH Curve pool, and then uses the acquired yETH to remove liquidity from the pool.

The core manipulation leverages the interface asymmetry described in Section 0x1 (Background): add_liquidity() allows arbitrary-proportion deposits, whereas remove_liquidity() withdraws assets proportionally by pool weights (highlighted in the red rectangle in the above Figure). By repeatedly cycling add → remove operations, depositing only selected assets while withdrawing all assets proportionally, the attacker progressively drives the pool into a severely imbalanced state:

| Asset | Weight | Before | After | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (sfrxETH) | 20% | 628,097,482,908,289,585,170 | 684,908,495,923,316,419,717 | +9.04% |

| 1 (wstETH) | 20% | 376,569,216,105,249,117,091 | 684,906,088,027,654,432,883 | +81.88% |

| 2 (ETHx) | 10% | 187,473,530,249,048,974,586 | 410,441,661,092,336,995,160 | +118.93% |

| 3 (cbETH) | 10% | 267,387,722,745,796,900,349 | 3,532,430,695,689,175,233 | -98.68% |

| 4 (rETH) | 10% | 201,828,029,369,446,137,136 | 410,441,659,865,060,509,563 | +103.36% |

| 5 (apxETH) | 25% | 753,792,636,209,697,936,333 | 549,134,446,963,315,842,411 | -27.15% |

| 6 (WOETH) | 2.5% | 49,640,000,870,620,479,267 | 655,788,758,768,556,847 | -98.68% |

| 7 (mETH) | 2.5% | 47,667,894,211,903,277,629 | 629,735,467,970,876,930 | -98.68% |

Assets 3 (cbETH), 6 (WOETH), and 7 (mETH) have been depleted by over 98%. This imbalance does not extract profit directly. It creates the numerical preconditions for the next phase.

0x3.2 Phase 2: Collapsing Supply to Zero (~$8.1M)

Goal: Drive the invariant product to zero, then drain the yETH supply to zero. This phase exploits only the primary vulnerability (unsafe arithmetic) and caused ~90% of total losses.

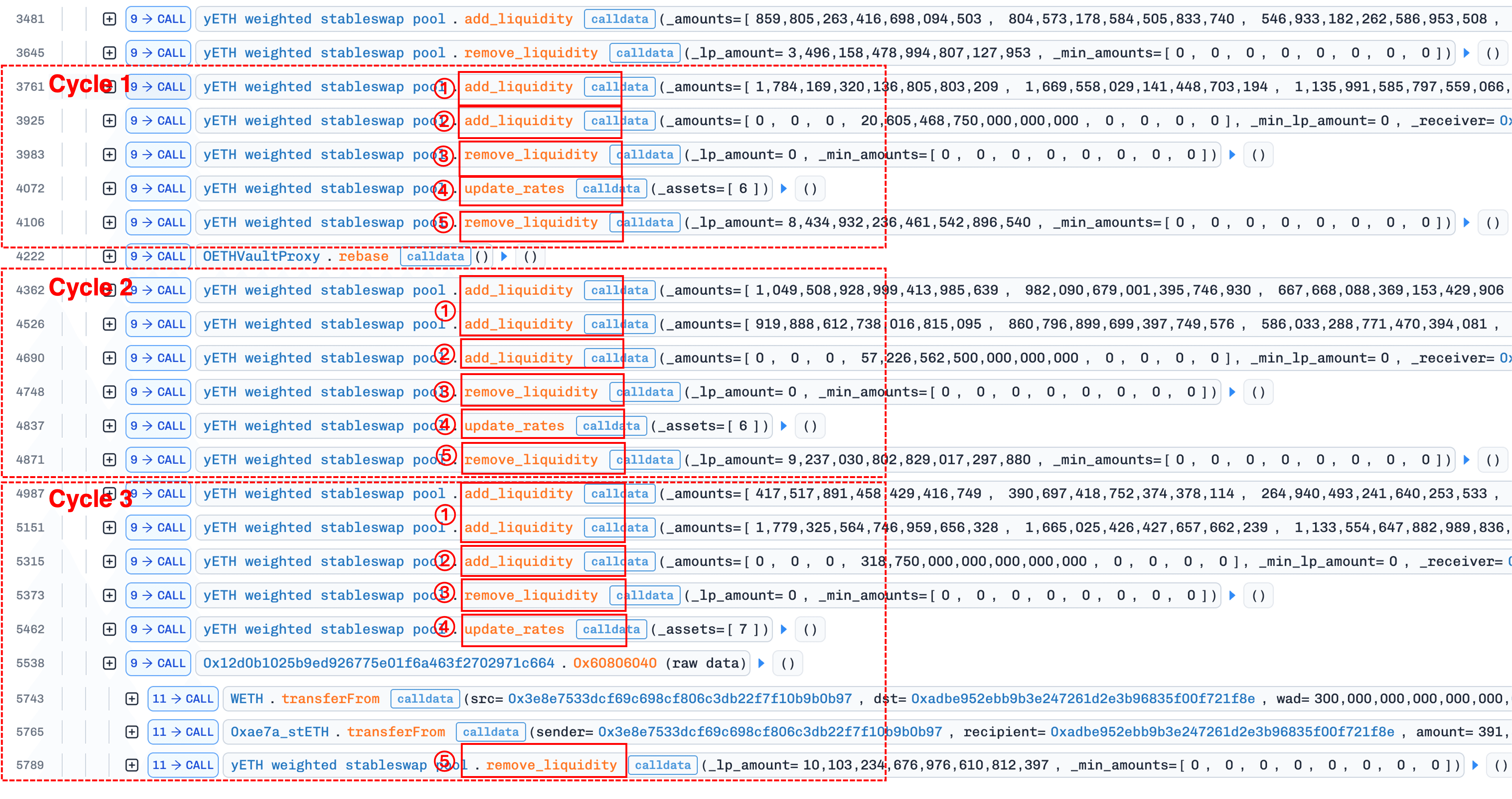

This phase uses a repeating five-step cycle, executed three times:

- Corrupt the product via

add_liquidity(); - Establish precondition for correction via

add_liquidity(); - Reset the product via

remove_liquidity()with 0 yETH; - Correct the supply via

update_rates(); - Withdraw assets via

remove_liquidity().

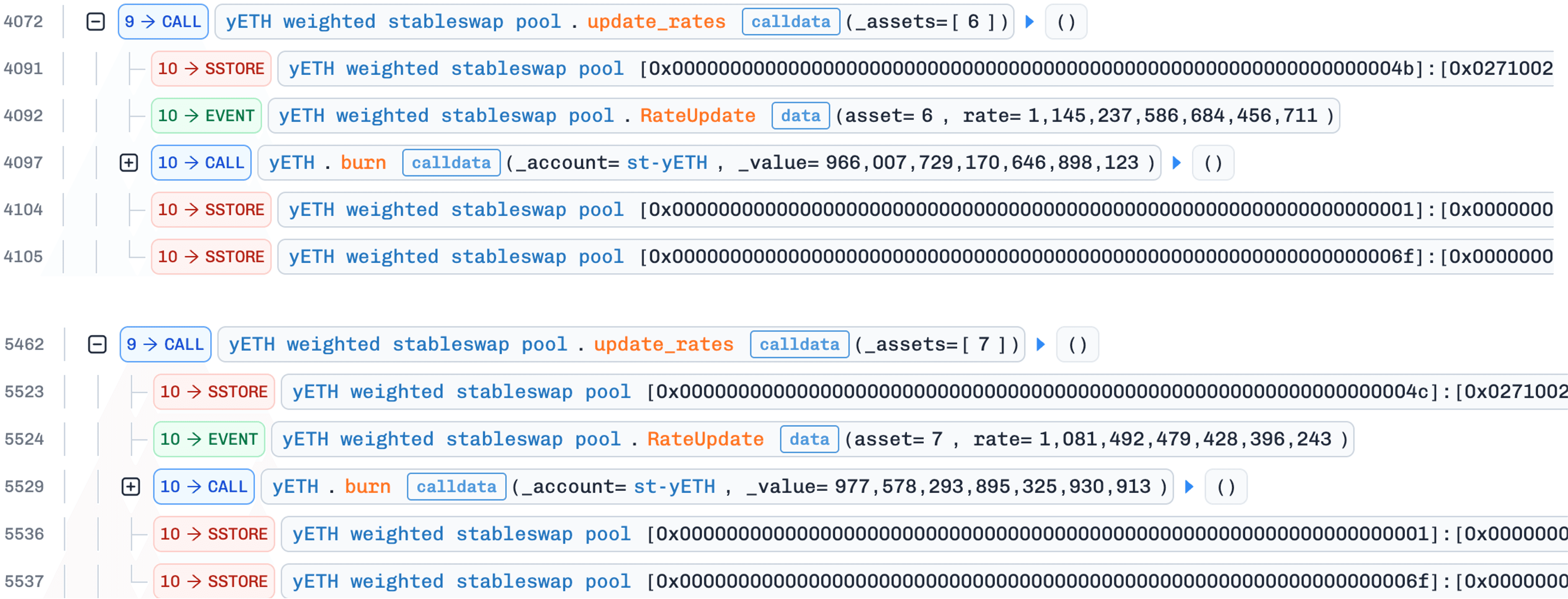

The figure below shows the transaction trace, where three repetitions of the five-step cycle are clearly visible:

1. Corrupt the product via `add_liquidity()`

The attacker deposits large amounts of high-weight assets (indices 0, 1, 2, 4, 5: sfrxETH, wstETH, ETHx, rETH, apxETH), each roughly three times its current virtual balance.

add_liquidity() estimates the new product term via the incremental update in equation (5) (Section 0x1.3). Since for high-weight assets, the ratios are all fractions well below 1, raised to large powers. This drives from ~42e18 down to ~0.00353e18, a near-zero estimated product.

This tiny product enters _calc_supply(). In the iteration, the product update r = r * sp / s encounters the rounding-down condition described in Section 0x2 (Root Cause Analysis): the numerator falls below the denominator, and integer division floors r to zero. The function returns a zero product and an inflated supply (~vb_sum), causing the protocol to over-mint yETH.

2. Establish precondition for correction via `add_liquidity()`

The attacker adds single-sided liquidity for asset index 3 (cbETH, a depleted, low-weight asset), depositing ~6.5x the asset's current pool balance. This receives only a few yETH tokens, but rebalances the pool enough that the next iteration won't oscillate wildly.

Without this step, even after resetting the product to non-zero in Step 3, the iteration in Step 4 would still produce a zero product due to violent oscillations from the extreme imbalance. Our Foundry simulation confirms this: skipping Step 2 causes the correction in Step 4 to fail.

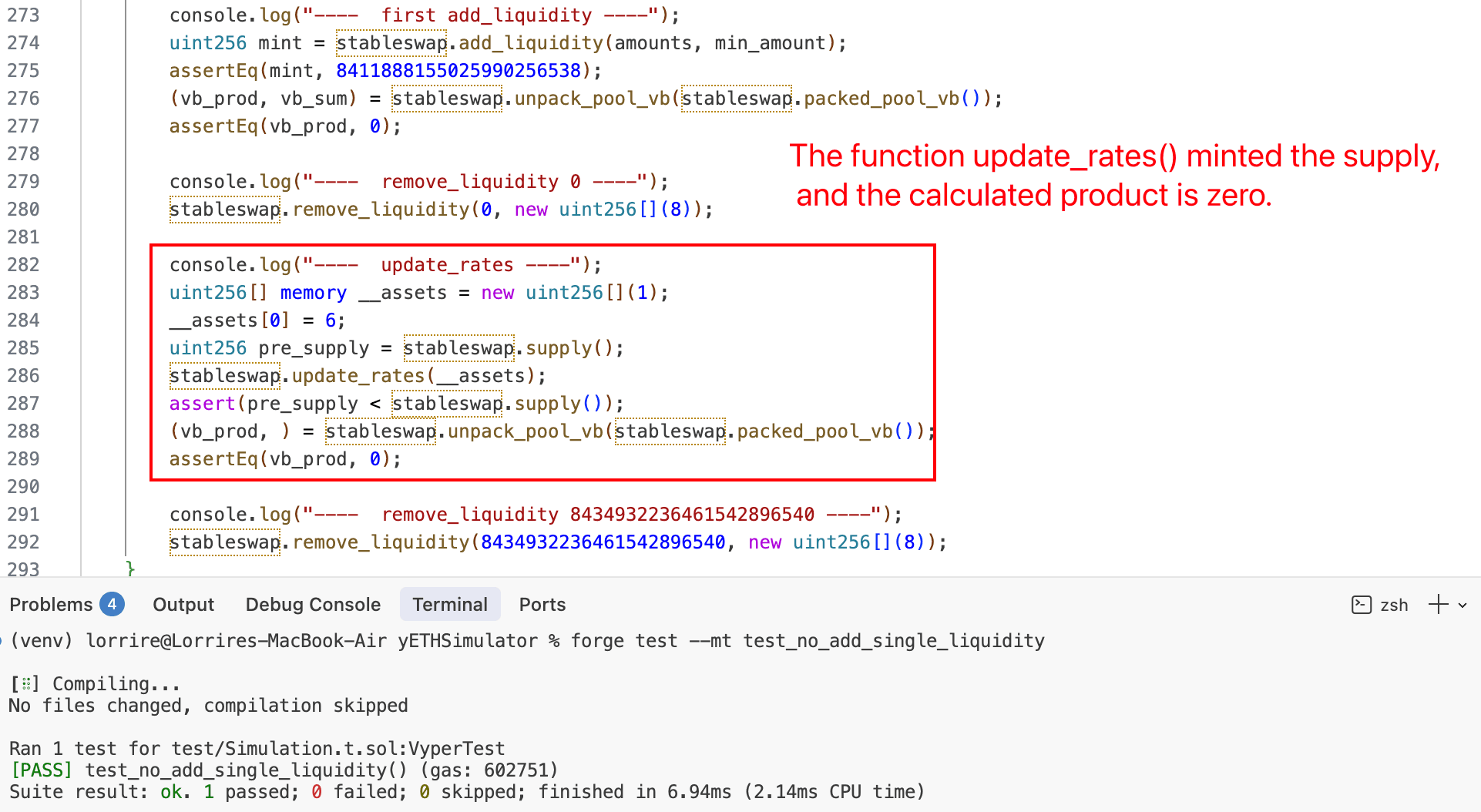

3. Reset the product via `remove_liquidity()` with 0 yETH

The attacker calls remove_liquidity() with amount 0. No tokens are withdrawn, but the function recalculates vb_prod from the current pool state using equation (4) (Section 0x1.3). Since the virtual balances are non-zero, this produces a non-zero product (~9.09e19), overwriting the corrupted zero value.

4. Correct the supply via `update_rates()`

The attacker calls update_rates() for asset index 6 (WOETH) or 7 (mETH). If the exchange rate has changed since the last update, the function triggers _calc_supply() with the restored (non-zero) product. This time, the iteration converges correctly and produces a supply value much lower than the current inflated one. The difference is burned from the yETH staking contract. According to the official post-mortem [2], this constitutes Protocol-Owned Liquidity (POL), meaning the burns reduce the protocol's position rather than the attacker's holdings. This asymmetry is critical: each cycle reduces total supply while the attacker's yETH balance remains intact.

The rate discrepancy itself is not a source of profit; it serves purely as a trigger mechanism. Among the three pool interfaces, only add_liquidity() and update_rates() invoke _calc_supply(); remove_liquidity() uses proportional scaling and does not. After Step 3 restores a non-zero product, the attacker needs to trigger _calc_supply() without depositing additional assets. Calling update_rates() with a stale rate accomplishes exactly this: the rate change triggers supply recalculation at zero cost to the attacker.

This explains a subtle aspect of the attack: during the preparation phase (Phase 1), the attacker deliberately avoided adding liquidity for WOETH and mETH. If those rates had been updated during add_liquidity(), no rate discrepancy would exist, and update_rates() in this step would not trigger _calc_supply().

5. Withdraw assets via `remove_liquidity()`

At the end of each cycle, the attacker withdraws assets via remove_liquidity().

How Profit Is Extracted

The profit mechanism works as follows: in Step 1, the attacker deposits LSTs and receives over-minted yETH (due to the corrupted product). In Step 4, when supply is corrected, the excess yETH is burned from the POL (staking contract), not from the attacker. In Step 5, the attacker withdraws LSTs proportional to their yETH holdings. Because POL absorbed the burn while the attacker's yETH balance remained intact, the attacker ends up withdrawing more LSTs than they deposited. This difference, extracted over three cycles, totals ~$8.1M.

Purpose of Rebase

The trace (between the first and the second cycle) also shows a call to OETHVaultProxy.rebase(), which triggers an OETH rebase: the OETH balance held by the WOETH contract increases, raising WOETH's effective exchange rate. This "saved" rate discrepancy is what makes Step 4 of the second cycle possible again: when update_rates() is eventually called, it detects the discrepancy and triggers _calc_supply().

Draining to zero

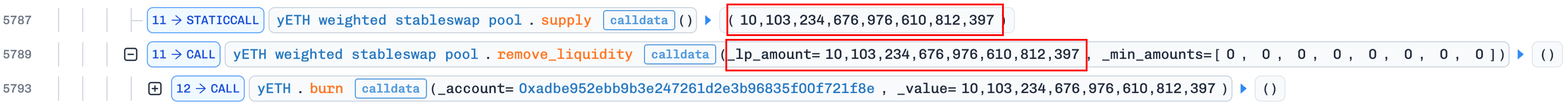

After repeating this five-step cycle three times, the attacker has reduced the pool's total supply below the amount of yETH they hold. A final remove_liquidity() call with the remaining supply drains it to ZERO.

The pool now holds zero supply, zero product, and zero vb_sum. This degenerate state violates the implicit design assumption that a pool with prior deposits would never return to its uninitialized state.

0x3.3 Phase 3: Exploiting Zero Supply for Additional Profit (~$0.9M)

Goal: Mint an enormous amount of yETH from the degenerate pool state, then swap it for real assets. This phase exploits the co-dependent combination of the secondary vulnerability (non-disabled bootstrap path) and Failure Mode B (underflow), together contributing ~10% of total losses.

1. Minting via underflow

With total supply at zero, the attacker calls add_liquidity() with dust amounts (balance [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 9]).

Since prev_supply == 0, the code enters the bootstrap path described in Section 0x2 (Root Cause Analysis): it bypasses stored state and recomputes vb_prod and vb_sum from scratch via _calc_vb_prod_sum(), then passes these into _calc_supply(). This is the second vulnerability in action: the attacker has driven the pool back to its uninitialized state, gaining control over the initial conditions fed to the solver.

With all virtual balances at dust levels (exchange rates close to 1e18), the computed values are:

vb_sum= 16vb_prod≈ 9.13e20_supply=vb_sum= 16

Inside _calc_supply(), the variables are initialized as:

l=_amplification * _vb_sum≈ 4.5e20 × 16 ≈ 7.2e21d=_amplification - PRECISION≈ 4.49e20s=_supply= 16r=_vb_prod≈ 9.13e20

Now the subtraction l - s * r:

This is negative. In unchecked uint256 arithmetic, unsafe_sub wraps this to approximately , an astronomically large value. After division by d (~4.49e20), the resulting supply estimate is ~2.35e56, and the protocol mints this entire amount to the attacker. This underflow is only possible because total supply was driven to zero in Phase 2; under any non-degenerate pool state, l > s * r holds and the subtraction is safe.

2. Swapping for real assets

The attacker swaps part of the over-minted yETH for ~1,097e18 WETH in the yETH–WETH Curve pool, draining its WETH reserves. After accounting for the 800e18 WETH spent in Phase 1, the net profit was ~$0.9M.

Combined with the ~$8.1M in LST assets extracted during Phase 2, the attacker nets approximately $9 million in total profit after repaying flash loans.

Detailed fund flow analysis, including source of funds and destination addresses, has been covered in other published analyses (e.g., [2]) and is outside the scope of this article.

0x4 Correcting Misunderstandings

Most published analyses of this incident focus on the arithmetic symptoms without fully explaining how the attacker sets up the preconditions. Two specific claims deserve correction.

0x4.1 Claim: "Rounding mismatch between `pow_up()` and `pow_down()` corrupts the invariant"

A common interpretation attributes the root cause to the use of pow_up() in some code paths and pow_down() in others, arguing that the directional mismatch introduces exploitable inconsistencies.

We tested this directly: we modified the contract to use pow_down() uniformly (replacing all pow_up() calls) and re-ran the full attack simulation in Foundry. The exploit succeeded identically. The product still collapses to zero, the supply still drains, and the underflow still produces an inflated mint.

The rounding that enables the zero-product state is the floor division in r = unsafe_div(unsafe_mul(r, sp), s) inside the iteration loop, not the direction of rounding in the power functions used to estimate initial product values.

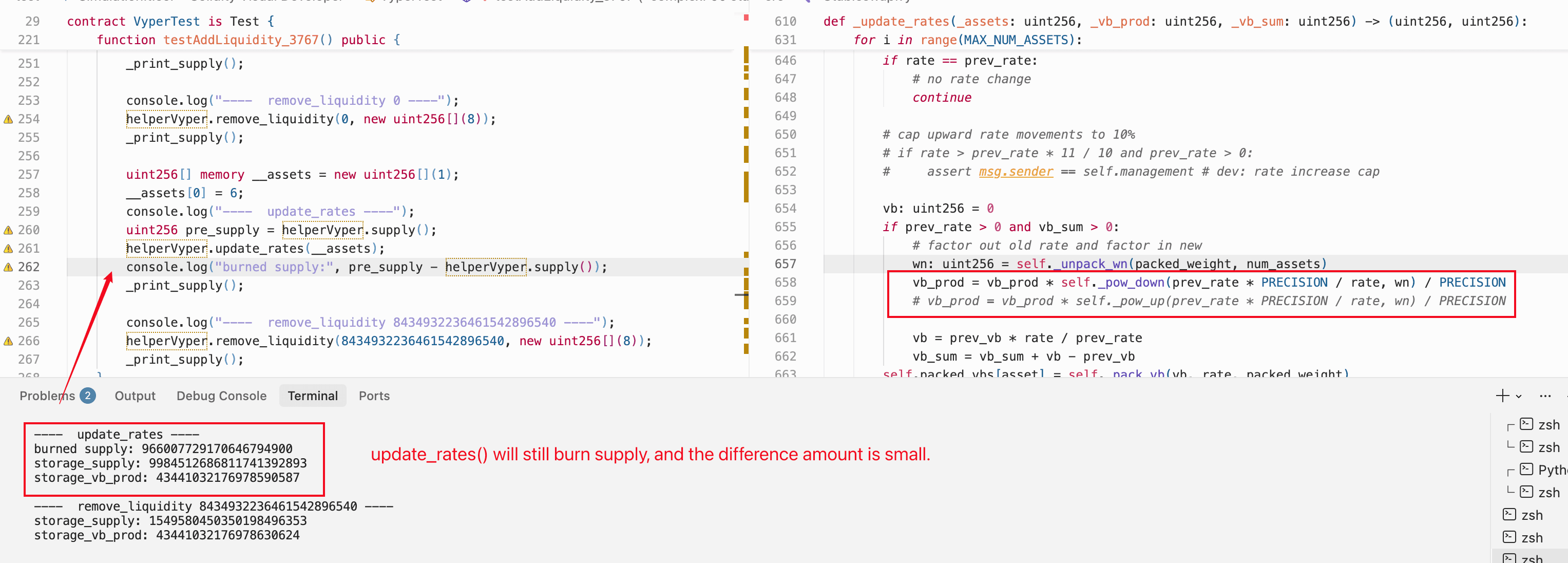

0x4.2 Claim: "Underflow in the second iteration zeros the intermediate term"

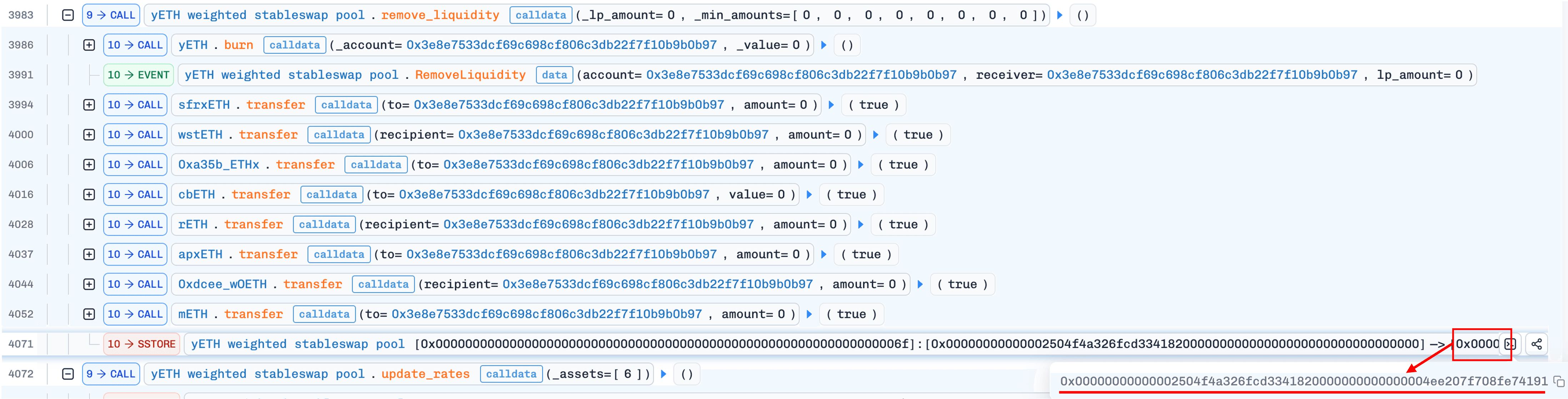

A widely-cited explanation holds that during the second iteration of _calc_supply(), an underflow in unsafe_sub produces sp ≈ 1.94e18, which then causes r to round down to zero.

We reproduced the exact intermediate values using both Foundry (on-chain replay) and Python (mathematical verification). The Foundry simulation traces _calc_supply() iteration by iteration:

======= _calc_supply iteration 0 =======

l = 4905875511098192451202650000000000000000

s = 2514373972590845290489 ← initial supply

r = 3538247433646816 ← initial product (very small)

d = 4490000000000000000000

sp = (l - s*r) / d ≈ 1.093e22 ← new supply jumps ~4x

new r ≈ 4.49e22 ← product inflates dramatically

======= _calc_supply iteration 1 =======

s = 10926206313726454855296 ← from previous sp

r = 44892226765713223838396 ← from previous inner loop

sp = 19113493328251743069 ← ≈ 1.91e19, legitimately small

new r = 0 ← rounds to zero!The critical observation: in iteration 1, sp evaluates to ~1.91e19. This is a legitimately small positive value, not an underflow artifact. The subtraction l - s*r produces a small positive result because the amplification-weighted sum l and the supply-product term s*r are close in magnitude at this iteration.

What zeros the product is what happens next: the inner loop computes r = r * sp / s, where sp (~1.91e19) is far smaller than s (~1.09e22). The numerator r * sp falls below the denominator s, and integer division floors the result to zero.

We verified this independently in Python, computing the same values with arbitrary-precision integers and confirming the subtraction does not underflow:

The product zeros out through rounding in division, not through underflow in subtraction. The unsafe_sub underflow that inflates supply occurs in a completely different context: Phase 3 of the attack, when dust liquidity is added to a pool that has been drained to zero supply.

0x5 Conclusion

The yETH exploit involved two vulnerabilities with asymmetric impact. Unsafe arithmetic in _calc_supply() was the primary root cause: its rounding-down failure (Failure Mode A) independently enabled ~$8.1M in losses through Phase 2 alone. The non-disabled bootstrap path was a secondary vulnerability; combined with the underflow failure (Failure Mode B), it enabled an additional ~$0.9M in Phase 3, but only after Phase 2 had already drained supply to zero. This loss breakdown distinguishes the present analysis from other published reports, which do not separate Phase 2 and Phase 3 profits.

The official post-mortem [2] identifies five root causes. We reclassify them as two defects (unsafe arithmetic consolidating official #1 and #5; non-disabled bootstrap path as #4) and two architectural preconditions (#2 asymmetric Π handling; #3 POL-enabled zero-supply state). The distinction: defects are implementation bugs that violate the design intent (the solver should not produce zero products or underflow), while preconditions are design choices that function as intended but create exploitable attack surface when combined with defects.

Recommendations

- Checked arithmetic in invariant solvers. Use

safe_divandsafe_subwith explicit revert on underflow/overflow, even at the cost of gas efficiency. The solver runs at most 256 iterations, and the gas overhead is negligible compared to the security risk. - Bound checks on intermediate values. Validate that the product term remains within a sane range between iterations. A product that drops to zero or a supply estimate that increases by orders of magnitude between iterations signals a degenerate state.

- Imbalance limits. Enforce maximum deviation between any asset's virtual balance and its target weight-proportional balance. This would prevent Phase 1 from creating the preconditions.

- Invariant monotonicity checks. After

_calc_supply()returns, verify that the new supply is consistent with the direction of change (liquidity addition should never decrease supply, rate updates should not produce 10x changes, etc.). - Permanently disable initialization paths. After the pool's first deposit, gate the

prev_supply == 0bootstrap branch so it cannot be re-entered. This would prevent Phase 3 entirely. - Prevent zero-supply states. Ensure that protocol-level burns (from POL or staking contracts) cannot reduce total supply to zero while the pool holds non-zero balances. A minimum supply floor would block the transition to the degenerate state that enables bootstrap re-entry.

- Real-time anomaly detection. Monitor for abnormal state transitions (such as product terms dropping to zero, supply changing by orders of magnitude, or repeated add/remove cycles in short timeframes) and trigger alerts or circuit breakers before losses compound.

References

- Yearn Finance incident announcement

- Yearn Security post-mortem

- yETH documentation

- yETH whitepaper: invariant derivation

- Attack transaction on BlockSec Explorer

- BlockSec: Analysis of the Balancer boosted pool incident (August 2023)

About BlockSec

BlockSec is a full-stack blockchain security and crypto compliance provider. We build products and services that help customers to perform code audit (including smart contracts, blockchain and wallets), intercept attacks in real time, analyze incidents, trace illicit funds, and meet AML/CFT obligations, across the full lifecycle of protocols and platforms.

BlockSec has published multiple blockchain security papers in prestigious conferences, reported several zero-day attacks of DeFi applications, blocked multiple hacks to rescue more than 20 million dollars, and secured billions of cryptocurrencies.

-

Official website: https://blocksec.com/

-

Official Twitter account: https://twitter.com/BlockSecTeam