On August 25, 2025, with the assistance of Cantina and Seal911, Panoptic conducted a white hat rescue operation, securing approximately $400K in at-risk funds [1]. The root cause was a flaw in the construction of s_positionsHash: the protocol used XOR to aggregate Keccak256 hashes of position IDs into a single fingerprint. While individual Keccak256 hashes remain collision-resistant, XOR's mathematical linearity makes the composite fingerprint insecure. An attacker can generate a set of forged position IDs whose XOR-aggregated hash matches any target fingerprint, bypassing the protocol's position verification and withdrawing collateral without repaying debt.

Background

Panoptic is a decentralized perpetual options trading protocol built on Ethereum that enables users to trade put and call options.

The function withdraw() has an input parameter positionList, which consists of a set of tokenIds. Each tokenId represents a position. The function withdraw() checks the debt status of each position based on s_positionsHash and then retrieves the user's collateral.

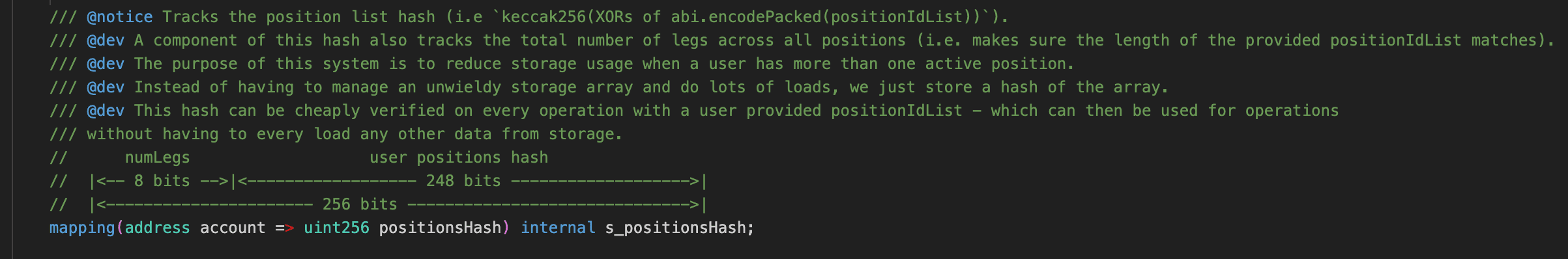

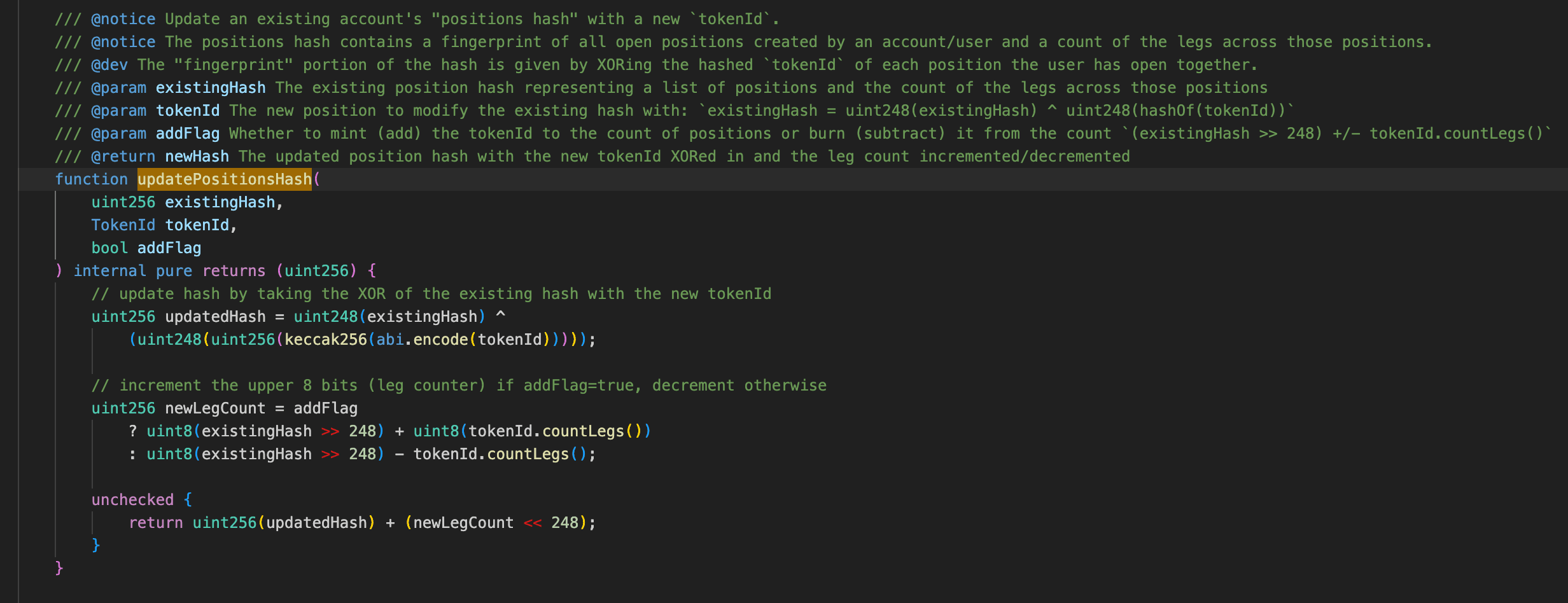

To save gas, the protocol does not store every position (i.e., tokenId) of the user. Instead, it calculates a fingerprint based on all the user's tokenIds and records it in s_positionsHash. The most significant 8 bits of each s_positionsHash represent numLegs, while the lower 248 bits represent the user position hash.

For each passed tokenId, the protocol calculates its hash, takes the lower 248 bits, and updates the user position hash by performing a bitwise XOR with the lower 248 bits of the current s_positionsHash.

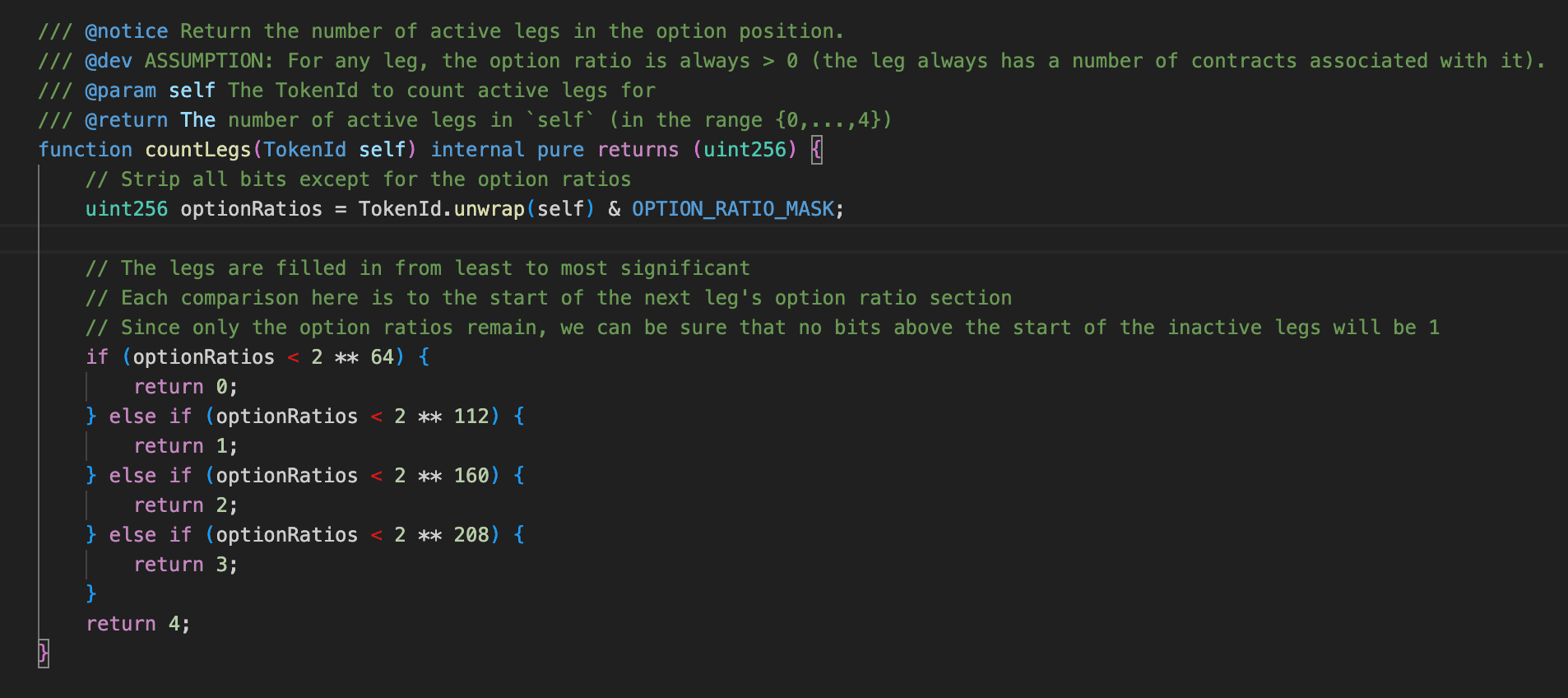

Simultaneously, countLegs is adjusted based on the numerical range of the tokenId: it remains unchanged when tokenId is below , and increases by 1, 2, or 3 when in the ranges , , and respectively. This is finally written to the top 8 bits of s_positionsHash to update numLegs.

Vulnerability Analysis

The root cause is a flaw in the contract's algorithm for constructing s_positionsHash, specifically the use of the XOR operation to aggregate Keccak256 hash results. While a single hash function remains secure, the mathematical linearity of the XOR operation renders the overall fingerprint algorithm (i.e., the XOR sum of hashes) insecure [2].

Linearity implies that an attacker does not need to break the hash function itself (i.e., reversing the tokenId from the hash). Instead, they can employ a combinatorial strategy: generating a large number of random tokenIds, calculating their Keccak256(tokenId), and from these hash values, selecting a specific subset such that the XOR sum of these tokenId hashes exactly matches the victim's target fingerprint.

This allows an attacker to pass a set of forged tokenIds when calling withdraw() to pass the health check and retrieve all collateral corresponding to s_positionsHash.

Theory

Assume the user's position fingerprint s_positionsHash has a user position hash of and numLegs of , with user tokenIds . Thus:

Here, each 248-bit hash value can be viewed as a 248-dimensional vector.

Therefore, resides in a 248-dimensional space composed of 0s and 1s (). In this space, the XOR operation is equivalent to vector addition (Appendix I).

The attacker's goal is to find 248-dimensional vectors from all of the available vectors such that the lower 248 bits of their XOR sum equal . Thus, we can formulate the attacker's objective as a system of linear equations:

Specifically, we do not need to try to construct directly. Instead, we select linearly independent hash vectors (where equals the dimension 248) and use them as column vectors to construct an matrix :

The problem then transforms into finding a coefficient vector such that:

Where , and .

According to linear algebra theory, as long as matrix is full rank, it spans the entire -dimensional space. This means that for any target , the system of equations has a unique solution. After solving for , we simply retain those vectors for which ; their XOR sum is .

Example

To facilitate understanding, we demonstrate this construction process with a case study. Assume the vectors are 3-dimensional, with each dimension consisting only of 0 or 1, and the target hash value is 101, i.e., .

Next, we randomly generate 3 hash values:

We construct matrix using these three vectors as columns and set up the equation :

Solving via Gaussian elimination, we obtain . This means we need to select and (corresponding to ), and their XOR sum exactly equals the target .

Selecting n Linearly Independent Vectors

As previously mentioned, to solve , we need to construct a full-rank matrix . Given that we are dealing with an extremely large vector space (), the core question is: How do we quickly select linearly independent vectors from this vast space?

Consider the simplest method: randomly generating tokenIds and selecting their hash results as vectors.

Over , the probability that randomly selected -dimensional vectors form a full-rank matrix is:

When is large (in this example, ), this probability converges to a constant (Appendix II):

This means each random attempt has approximately a 28.9% probability of success. On average, an attacker only needs about 3.5 attempts to find a set of linearly independent vectors. Therefore, the computational cost is extremely low, and the attacker can quickly construct a matrix that satisfies the conditions.

To control the countLegs in the top 8 bits, we only need to adjust the range of the randomly generated tokenId values based on the target countLegs.

For example, if we want the numLegs in the forged fingerprint to be 0, we simply ensure that the randomly generated tokenIds are all less than . Since the leg increment for tokenIds in this range is 0, regardless of which vectors the Gaussian elimination solution selects, the final accumulated numLegs will inevitably be 0.

Attack Analysis

The white hat rescuer initiated multiple rescue transactions. For simplicity, the following discussion is based on just one of these transactions [3].

The core logic consists of the following 5 steps:

- Borrow 0.23e8 WBTC and 28e18 WETH via flash loan from Aave.

- Deposit 0.23e8 WBTC and 28e18 WETH into the poWBTC contract and the 0x1f8d_poWETH contract.

- Call

mintOptions()of thePanopticPoolcontract with a normalpositionIdListto borrow funds and open a leveraged position. - Call

withdraw(), passing the forgedtokenIds. Because these forged positions have apositionSizeof 0, the function returnstokenRequiredas 0, meaning the total collateral required for all positions is erroneously calculated as zero. Meanwhile, thes_positionsHashgenerated by thesetokenIds is exactly the same as the one generated in step 3, allowing the rescuer to retrieve all collateral without repaying any debt. - Repay the flash loan and execute the next round.

Summary

This incident highlights two compounding flaws that together enabled unauthorized collateral withdrawal.

- XOR is not a secure aggregation function for hashes. Keccak256 is collision-resistant, but XOR's linearity means the XOR sum of multiple hashes does not inherit that property. Constructing a set of inputs whose hashes XOR to any target value reduces to solving a system of linear equations over , which is computationally trivial. Hash composition requires operations that preserve collision resistance, such as concatenation followed by re-hashing.

- Missing validation of position IDs. The protocol did not verify whether passed

positionIds corresponded to valid option positions. Values below carry acountLegsof 0 and apositionSizeof 0, meaning the forged positions incur no debt. This allowed the attacker to pass the health check with zero collateral requirement while matching the target fingerprint.

Reference

Appendix

The following two appendices provide a mathematical explanation and proof of the statements in the main text, namely that the XOR operation is equivalent to vector addition (Appendix I) and the probability that a random matrix is full rank (Appendix II).

Appendix I

In the finite field , addition is defined as addition modulo 2:

Observation shows this is identical to the Exclusive OR (XOR, symbol ) logic operation.

For the -dimensional vector space (in this case ), the addition of two vectors and is defined as component-wise modulo 2 addition:

Therefore, in the vector space, vector addition is equivalent to bitwise XOR operation on vector components.

Appendix II

To make the matrix full rank, these vectors must be linearly independent.

The first vector can be any vector in except the zero vector, providing choices; the second vector must not reside in the subspace spanned by , which contains vectors, leaving choices; following this logic, the -th vector cannot be in the subspace spanned by the previous vectors, resulting in possible choices.

The total number of such matrices (i.e., the order of ) is:

And the total number of all possible matrices is .

Thus, the probability is:

Letting , we can rewrite this expression as:

As , this product converges to a constant:

This means that for large , the probability that a random matrix is full rank is approximately 28.9%.

About BlockSec

BlockSec is a full-stack blockchain security and crypto compliance provider. We build products and services that help customers to perform code audit (including smart contracts, blockchain and wallets), intercept attacks in real time, analyze incidents, trace illicit funds, and meet AML/CFT obligations, across the full lifecycle of protocols and platforms.

BlockSec has published multiple blockchain security papers in prestigious conferences, reported several zero-day attacks of DeFi applications, blocked multiple hacks to rescue more than 20 million dollars, and secured billions of cryptocurrencies.

-

Official website: https://blocksec.com/

-

Official Twitter account: https://twitter.com/BlockSecTeam