On March 5, 2025, a third-party resolver contract integrated with the 1inch's Fusion V1 protocol suffered a coordinated exploit that resulted in total losses of over $5 million. The root cause was an unsafe calldata reconstruction in the settlement flow, where an attacker-controlled interaction length triggered a pointer underflow during suffix assembly, allowing forged settlement data to be injected. The exploit was further enabled by a misplaced trust boundary: resolver contracts implicitly trusted all calldata forwarded by the settlement contract based solely on msg.sender, causing attacker-controlled data to inherit settlement-level authority despite passing all access control checks.

This incident stands out as one of the most sophisticated DeFi exploits of 2025 not because of a novel financial primitive, but due to its exploitation of low-level ABI and memory layout assumptions, blurring the line between smart contract vulnerabilities and classical binary exploitation techniques.

Background

1inch's Fusion V1 Protocol

1inch is a decentralized exchange (DEX) aggregator that sources liquidity across multiple DEXs to provide users with optimized swap execution. Built on top of the aggregator’s limit order infrastructure, 1inch Fusion introduces a Dutch auction–based order matching model, allowing users to specify flexible execution parameters such as price ranges and swap time windows.

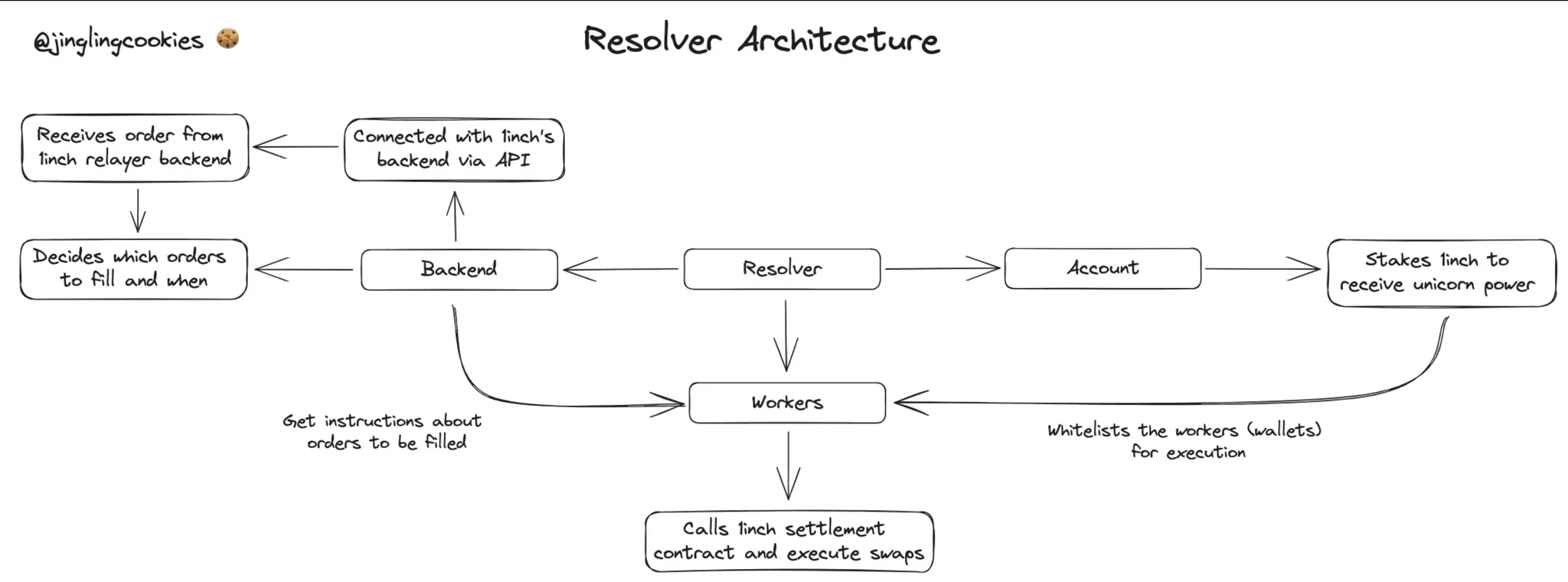

In the Fusion model, user orders are not filled directly by the protocol itself. Instead, they are executed by specialized actors known as resolvers. Resolvers can be viewed as privileged, whitelisted participants: to become eligible, they must stake tokens to obtain sufficient Unicorn Power, which serves as an economic gatekeeping mechanism.

Operationally, resolvers run their own off-chain infrastructure that interfaces with 1inch’s backend APIs to discover user orders and determine whether and when to fill them. Once a resolver decides to execute an order, it submits an on-chain transaction via a dedicated account to the Settlement contract, which performs the actual swap. (While Fusion involves a competitive Dutch auction among resolvers, this mechanism is not essential for understanding the attack and is therefore omitted here; for simplicity, we assume the resolver can directly satisfy the user’s order conditions.)

When executing a swap, a resolver may either source liquidity from external markets to deliver a better execution than the user’s minimum requirements, or directly settle the trade using its own assets. Any surplus value generated in the process accrues to the resolver as profit. The attack discussed in this blog targets such a resolver contract. Specifically, a contract used for on-chain market-making that held assets and had granted approvals to the Settlement contract, which ultimately led to the loss of those assets.

Order Processing and Fulfillment

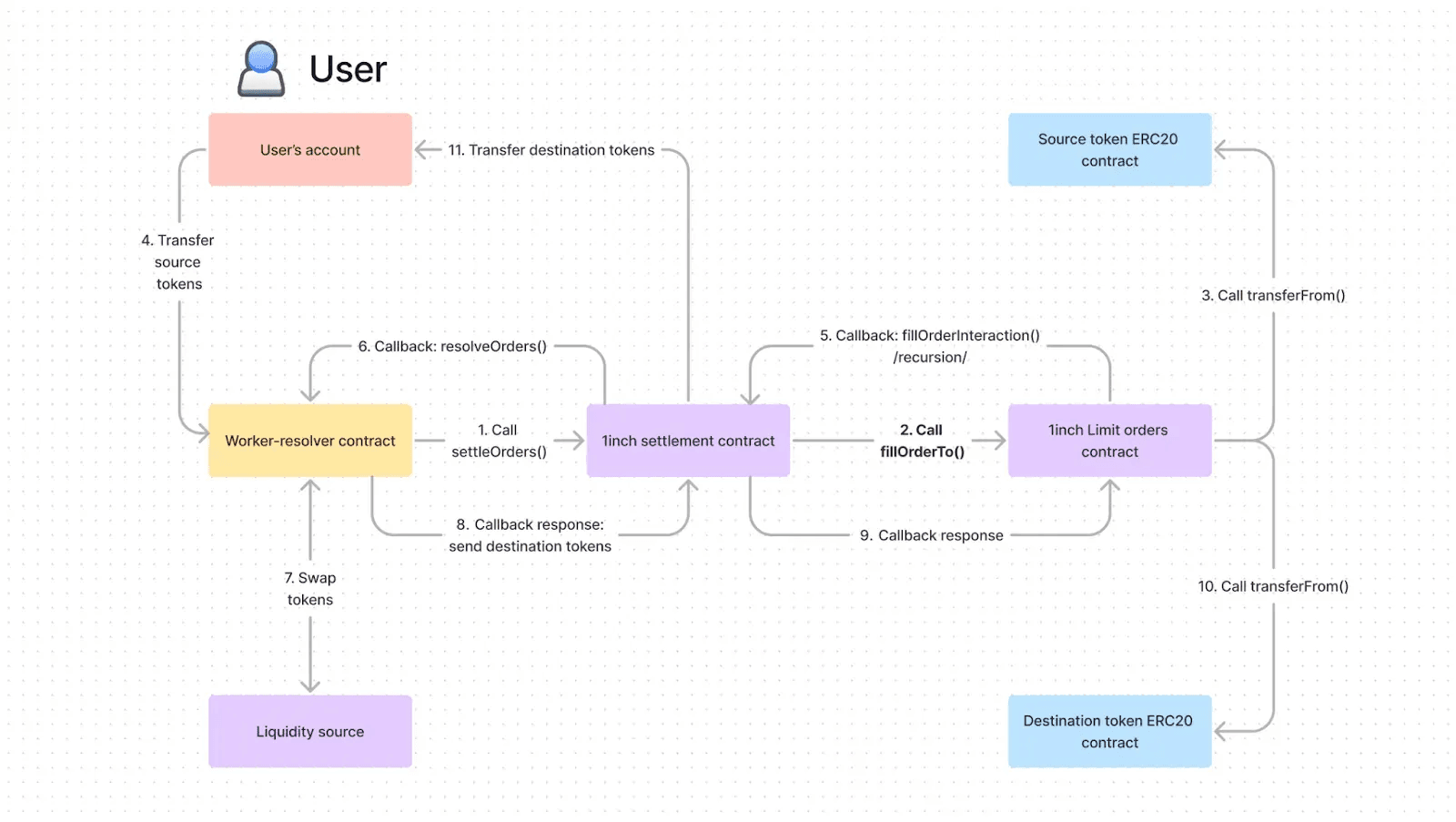

Order execution in 1inch Fusion is coordinated by the Settlement contract and follows a recursive settlement model driven by interaction data rather than a linear execution flow.

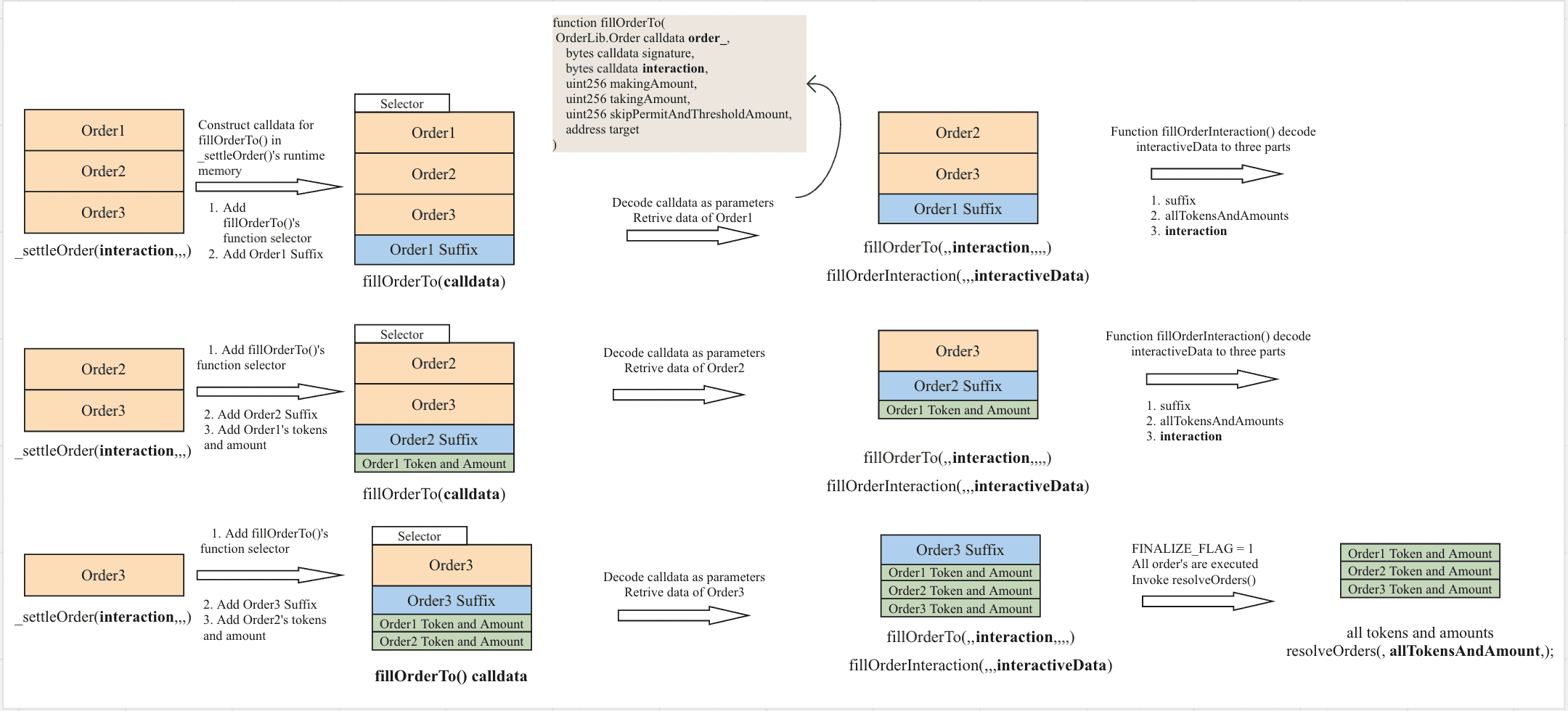

The process starts when a resolver calls the function settleOrders(), passing in calldata that encodes the first order together with an interaction payload. Instead of attempting to settle all orders at once, Settlement processes them incrementally through repeated invocations of the internal _settleOrder() function.

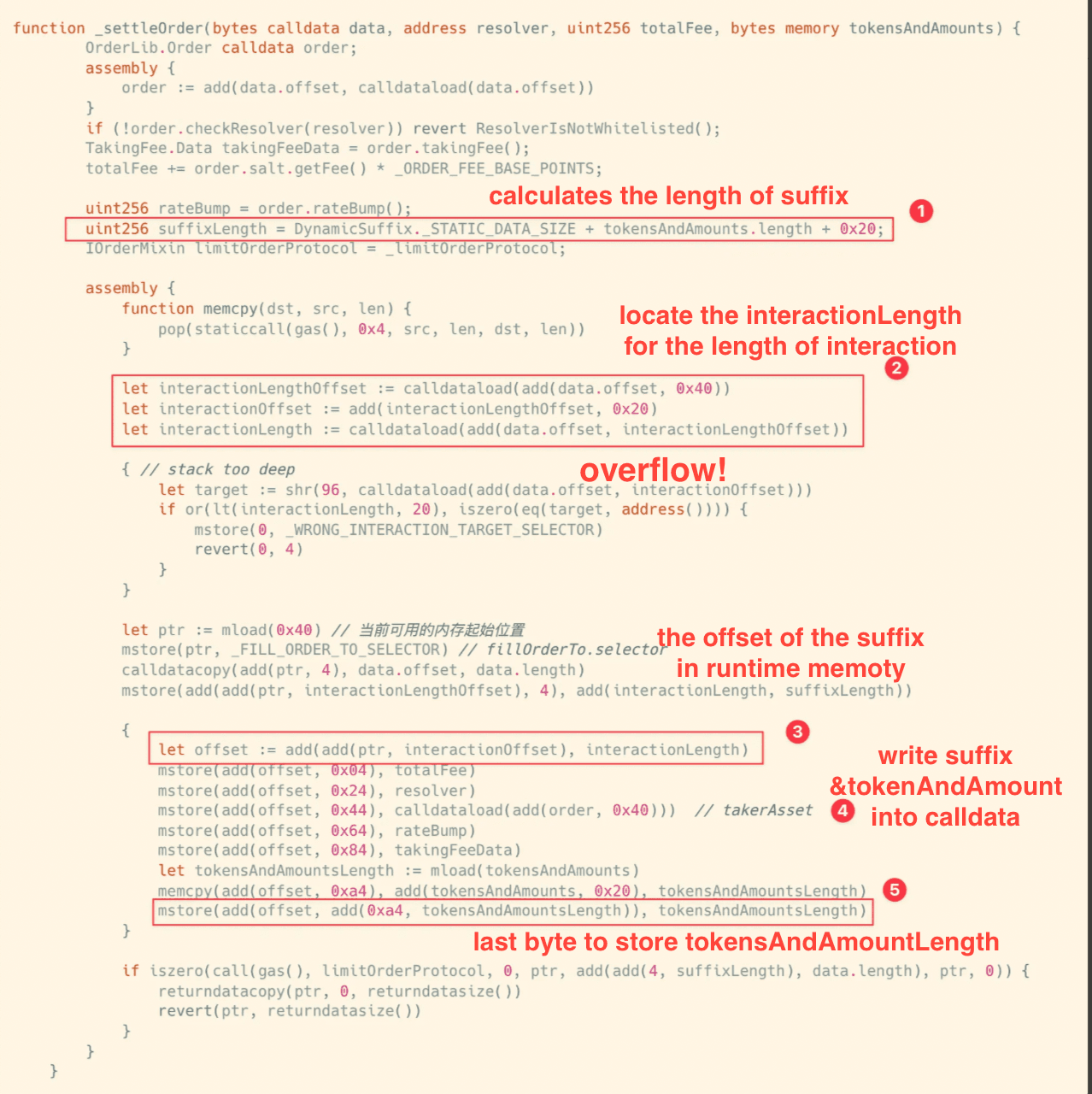

For each order, function _settleOrder() reconstructs a call to the Limit Order Protocol (AggregationRouterV5.fillOrderTo()) in memory. During this reconstruction, Settlement appends additional resolver-related context to the interaction data in the form of a dynamic suffix. This suffix carries execution metadata such as the resolver identity and accumulated fees and is treated as opaque by the Limit Order Protocol. It is forwarded unchanged and later decoded by Settlement itself during the interaction callback.

After the order is filled, control returns to Settlement via function fillOrderInteraction(). Based on the interaction data, Settlement either continues settlement by recursively invoking function _settleOrder() with the remaining interaction payload or transitions into a finalization step. In the final stage, Settlement forwards control to the resolver contract by invoking its resolveOrders() function, passing along the accumulated execution context.

This design allows multiple orders to be settled sequentially within a single transaction while deferring resolver-specific logic until all protocol-level execution steps have completed.

Vulnerability Analysis

The vulnerability arises from unsafe calldata reconstruction logic in the internal _settleOrder() function, specifically during the placement of the dynamic suffix appended to the interaction data.

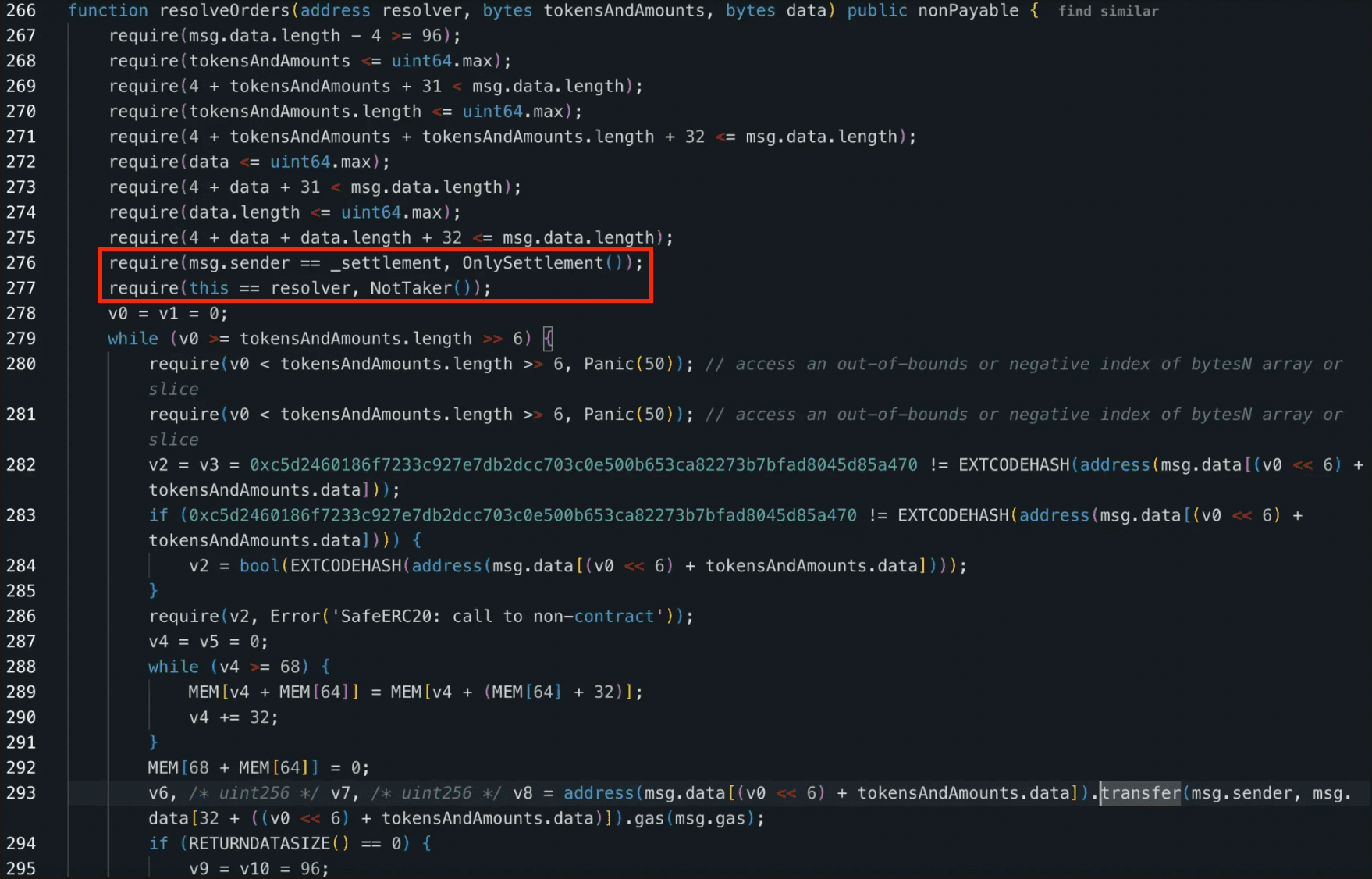

Resolver contracts are protected by explicit access control: they require that calls originate from the Settlement contract and that the resolver address supplied during resolution matches the resolver contract itself. These checks assume that the resolver identity propagated through the settlement process is constructed correctly and remains intact. This assumption depends on the correctness of how resolver-related data is encoded and appended during calldata reconstruction.

Concretely, the resolver's resolveOrders() enforces two guards:

require(msg.sender == _settlement, OnlySettlement());

require(this == resolver, NotTaker());The first check confirms the call originates from the Settlement contract. The second confirms that the resolver parameter (decoded from the suffix) matches the resolver contract's own address. Under normal operation, both fields are set correctly by _settleOrder(). Under the attack, both checks still pass: the attacker operates within the settlement flow (not outside it), so msg.sender is genuinely the Settlement contract; and the resolver field is decoded from the forged suffix, where the attacker has written the victim resolver's address.

During settlement, _settleOrder() reconstructs calldata in memory and appends a dynamic suffix that carries resolver-specific execution context. This suffix includes not only the resolver address, but also order-related information that the resolver relies on to interpret the settlement as legitimate. The suffix is written at a memory location computed as ptr + interactionOffset + interactionLength, where interactionLength is read directly from calldata as a full 32-byte value.

Because this offset calculation is performed without bounds checking, an attacker can control interactionLength to induce arithmetic overflow and manipulate where the suffix is written in memory. By doing so, the attacker can replace the intended suffix with a forged one, supplying an arbitrary resolver address together with attacker-controlled order context.

As a result, when the settlement flow later decodes the suffix, it may interpret the execution as originating from a legitimate resolver and involving valid order data, even though neither assumption holds. The attacker is effectively able to inject their own version of the order suffix while pretending to be the resolver to swap a few wei for millions.

Attack Analysis

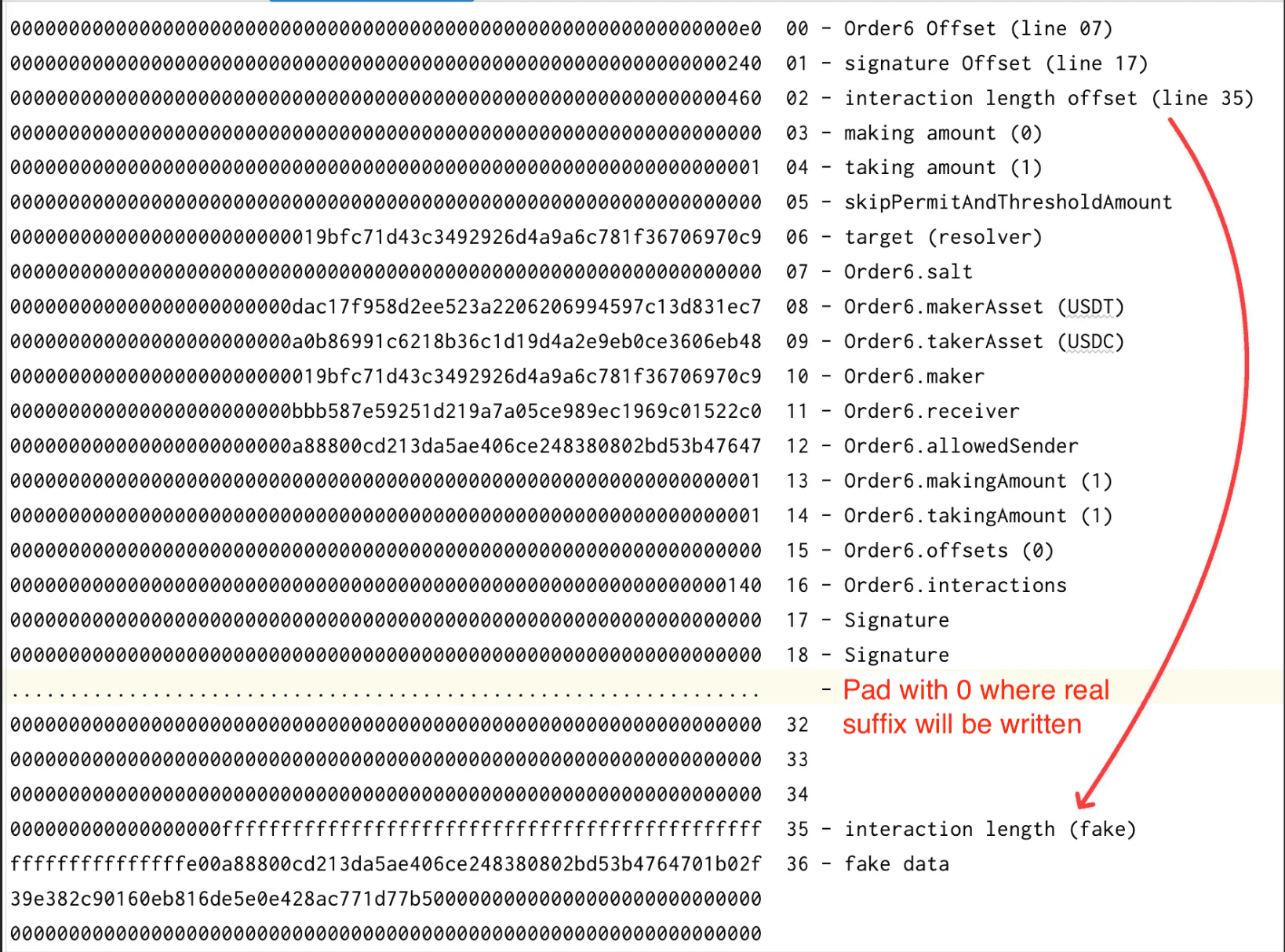

Taking transaction 0x74bc as an example. The attack begins with the creation of five valid orders that swap a negligible amount of tokens (a few wei) for a disproportionately large output amount. These orders are syntactically valid and pass protocol-level checks.

The attacker then pads the order calldata with a large region of null bytes. This padding serves as a controlled memory area that will later be overwritten due to incorrect suffix placement.

Crucially, the attacker specifies an invalid interactionLength value for the final order. The value is chosen as 0xffff…fe00, which corresponds to -512 when interpreted as a signed integer. Because interactionLength is treated as an unsigned 256-bit value and used directly in pointer arithmetic, this causes an arithmetic overflow when computing the suffix write offset.

The malicious interaction structure below is treated as a suffix:

From Forged Suffix to Asset Extraction

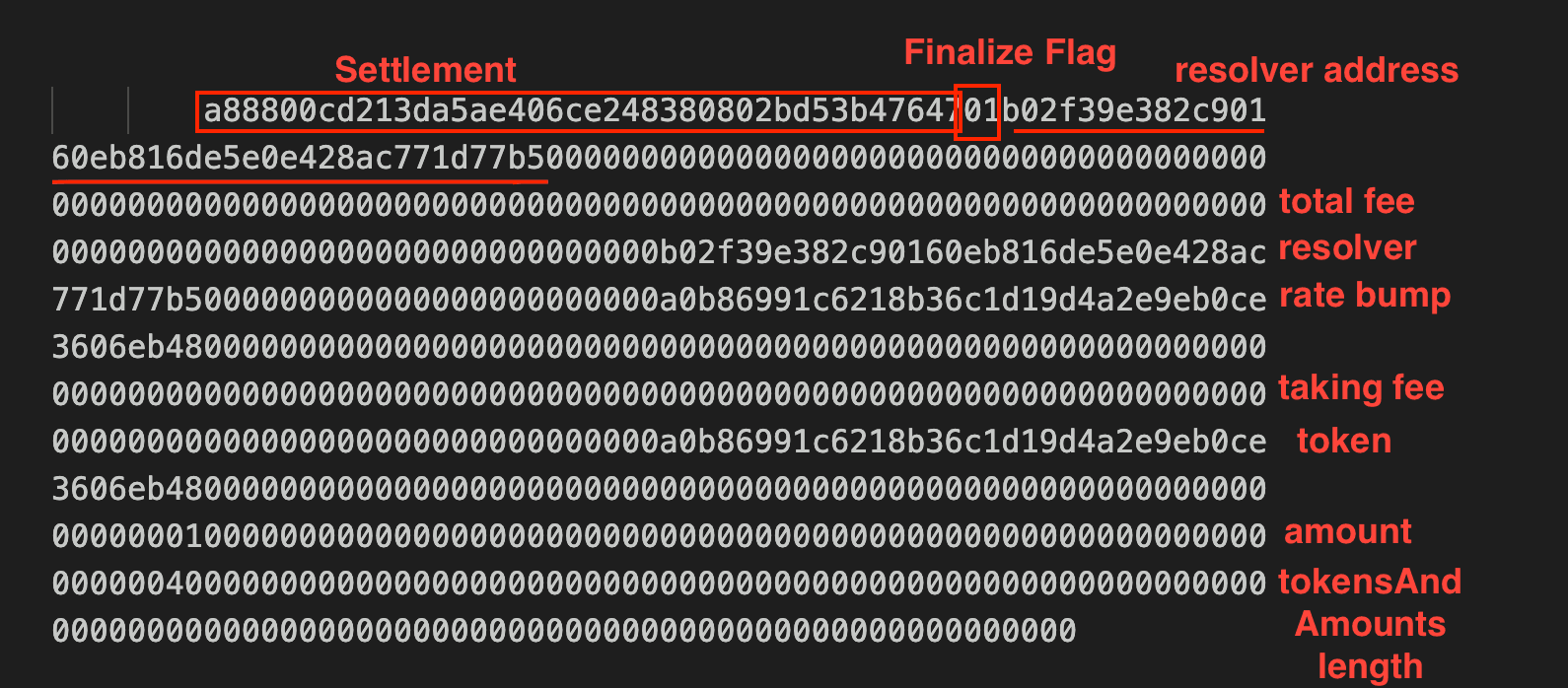

When Settlement processes the final order, the overflow causes the legitimate suffix to be written into the null-padded region, harmlessly overwriting zeros. The forged suffix placed by the attacker at the actual read position is then interpreted as legitimate settlement context.

The forged suffix sets the finalize flag, causing Settlement to transition from recursive order processing into the finalization step. Settlement calls resolveOrders() on the address decoded from the suffix, which is the victim resolver. As described in the Vulnerability Analysis, both access control checks pass: msg.sender is the Settlement contract (the call flows through the legitimate settlement path), and resolver matches the victim's address (written into the forged suffix by the attacker).

The victim resolver then processes the tokensAndAmounts array, which includes the asset addresses and amounts chosen by the attacker. Because the resolver has previously granted token approvals to the Settlement contract for normal operation, the transfer executes. The resolver sends its held assets to fulfill orders that required only a few wei of input, resulting in over $5 million in losses.

Summary

This incident targeted a third-party resolver contract integrated with the 1inch's deprecated Fusion V1 protocol, resulting in substantial losses, which highlights several important lessons.

- Unsafe Data Assumptions: Systems that rely on dynamically constructed input data must not assume lengths, offsets, or structure integrity when any part is user-influenced.

- Implicit Trust Chains: Security checks can be undermined when contracts rely on upstream components to preserve critical context, rather than validating it at each boundary.

- Legacy Surface Area: Supporting outdated components increases attack surface and makes protocols more vulnerable to novel exploitation techniques.

- Cross-Domain Exploitation Patterns: Vulnerabilities common in traditional software can reappear on-chain when low-level memory or data layout logic is involved.

Reference

-

https://blog.decurity.io/yul-calldata-corruption-1inch-postmortem-a7ea7a53bfd9

-

https://paragraph.com/@cookies-research/1inch-fusion-cost-efficient-mev-resistant-swaps

-

https://blog-zh.1inch.com/fusion-swap-resolving-onchain-component/#steps-5-6

About BlockSec

BlockSec is a full-stack blockchain security and crypto compliance provider. We build products and services that help customers to perform code audit (including smart contracts, blockchain and wallets), intercept attacks in real time, analyze incidents, trace illicit funds, and meet AML/CFT obligations, across the full lifecycle of protocols and platforms.

BlockSec has published multiple blockchain security papers in prestigious conferences, reported several zero-day attacks of DeFi applications, blocked multiple hacks to rescue more than 20 million dollars, and secured billions of cryptocurrencies.

-

Official website: https://blocksec.com/

-

Official Twitter account: https://twitter.com/BlockSecTeam