During the past week (Feb 2–Feb 8, 2026), BlockSec detected and analyzed six attack incidents, with total estimated losses of ~$3.8M. The table below summarizes these incidents, and detailed analyses for each case are provided in the following subsections.

| Date | Incident | Type | Estimated Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2026/02/02 | CrossCurve Incident | Access control | ~$2.8M |

| 2026/02/03 | GYD Incident | Improper input validation | ~$700K |

| 2026/02/05 | SOFI Token Incident | Token design flaw | ~$29.6K |

| 2026/02/05 | Unknown Staking Protocol Incident | Improper input validation | ~$71.6K |

| 2026/02/07 | LZMultiCall Protocol Incident | Arbitrary call | ~$142K |

| 2026/02/08 | Unknown Protocol Incident | Improper input validation | ~$63K |

1. CrossCurve Incident

Brief Summary

On February 2, 2026, the CrossCurve protocol was exploited, resulting in a loss of approximately $2.8 million. The root cause was that the ReceiverAxelar contract exposed a permissionless expressExecute() function, which bypassed the standard Axelar Gateway validation process. The receiver only performed peer address checks based on externally provided data. Consequently, the attacker constructed a malicious cross-chain call to trigger the burn and unlock mechanism, leading to the unauthorized release of 999,787,453e18 EYWA tokens to the attacker.

Background

CrossCurve is a cross-chain bridge protocol developed by Eywa.Fi, built on top of the Axelar cross-chain messaging framework.

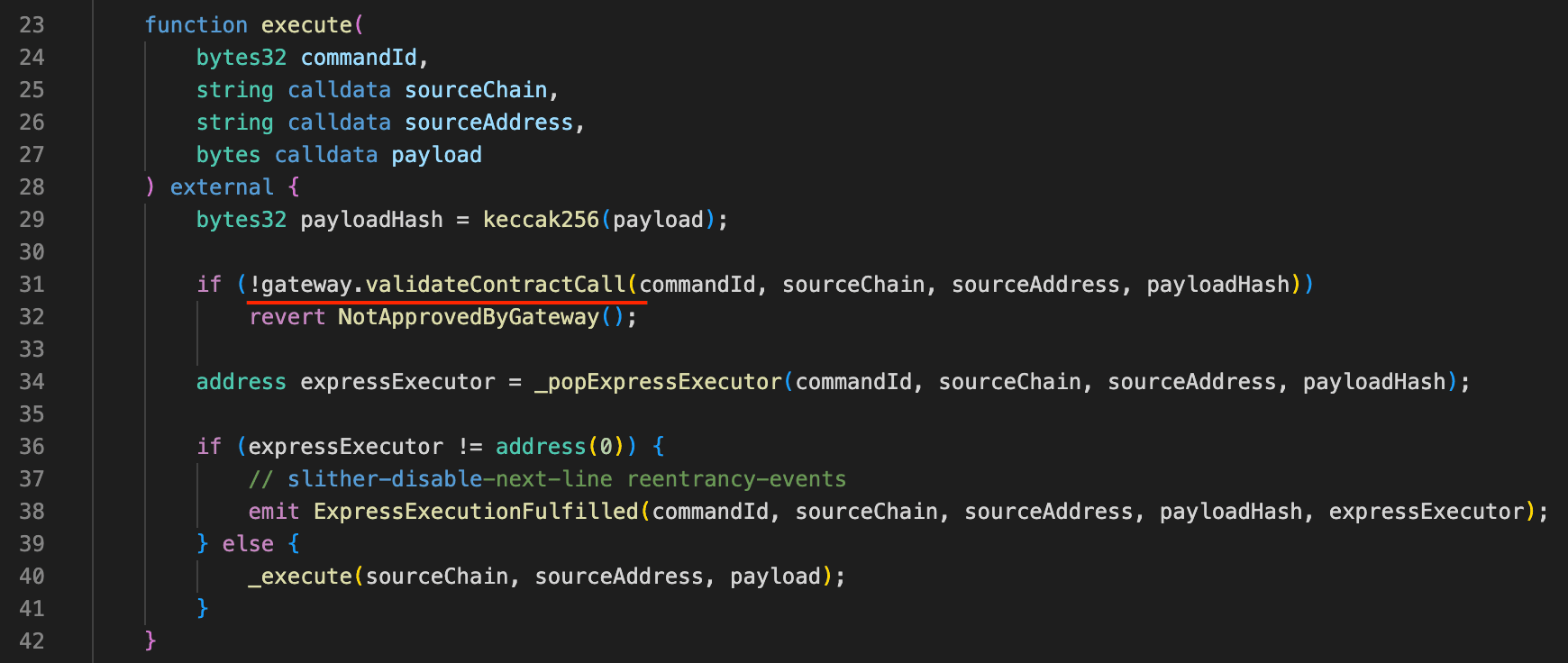

In Axelar's intended security model, cross-chain messages are relayed by the Axelar Gateway and must be explicitly validated on the destination chain via validateContractCall(). Only messages that have been cryptographically approved by the Gateway are allowed to proceed to execution.

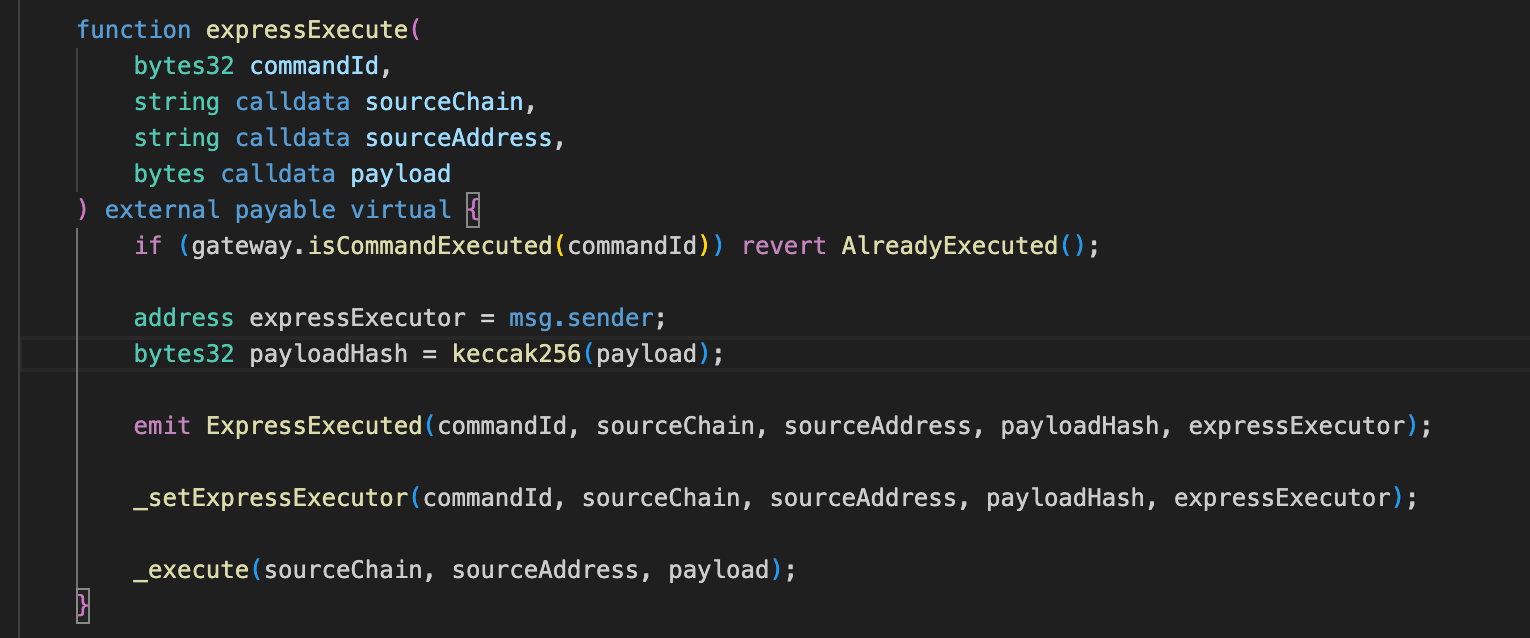

To reduce latency, Axelar also provides an express execution mechanism, where a receiver contract may optimistically execute a message before the Gateway finalizes validation. This design requires strict access control to ensure that only trusted executors can invoke express execution paths; otherwise, unvalidated cross-chain messages may be processed prematurely.

Vulnerability Analysis

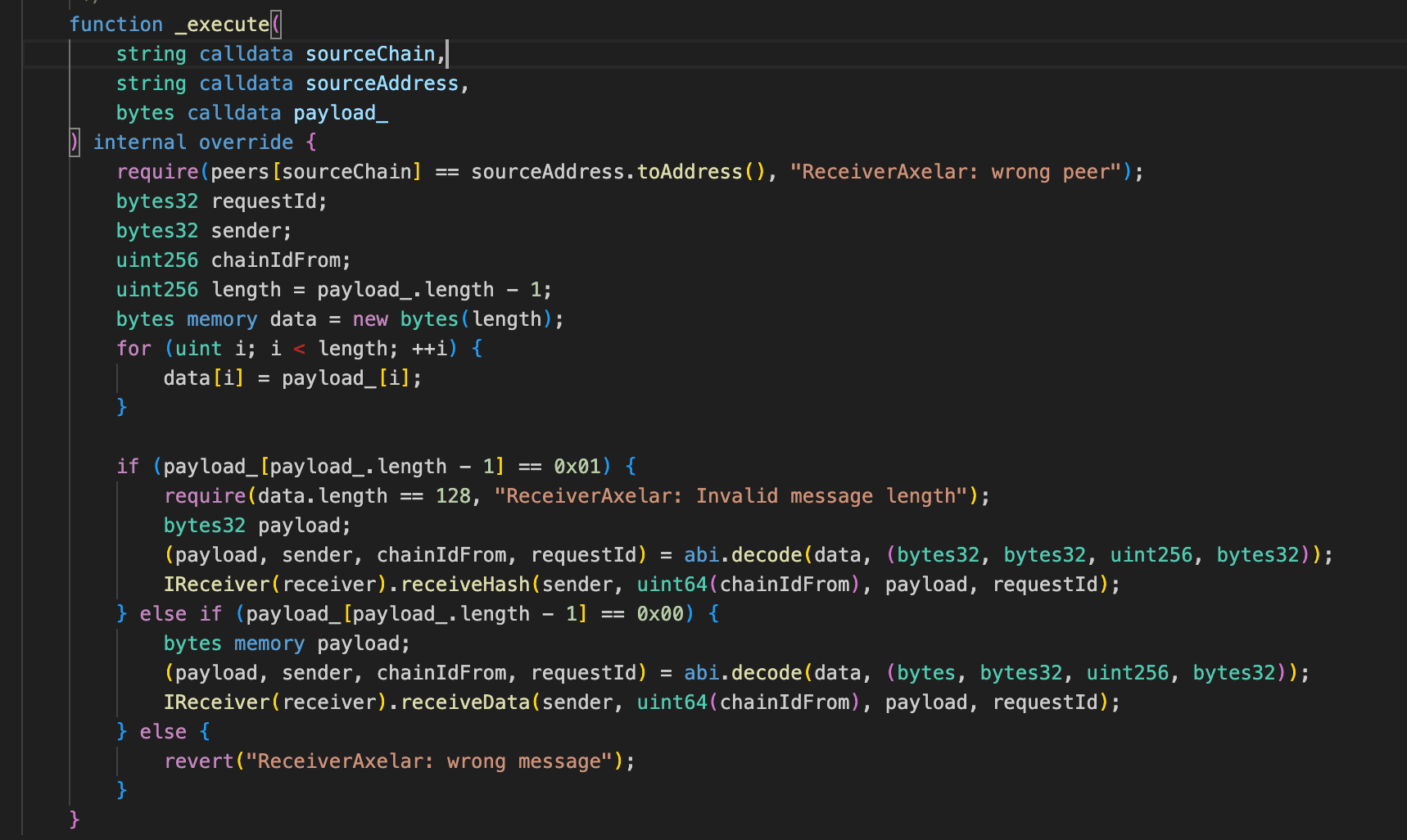

The root cause was that ReceiverAxelar exposed a permissionless expressExecute() function that could directly reach the privileged _execute() path without Axelar Gateway authorization.

In Axelar's correct security model, cross-chain messages must first be approved by the Gateway via proof-backed execution and then validated on the destination chain through validateContractCall(), which binds (commandId, sourceChain, sourceAddress, contractAddress, payloadHash) to a single authorized execution.

However, the expressExecute() path skipped this validation entirely. It relied only on a peer check using sourceChain and sourceAddress, both of which were attacker-controlled, and therefore provided no real security. This allowed the attacker to supply a spoofed message, force the receiveData branch, and execute an arbitrary payload that ultimately triggered unlock() on the Eywa CLP Portal, resulting in the unauthorized release of cross-chain assets.

Attack Analysis

-

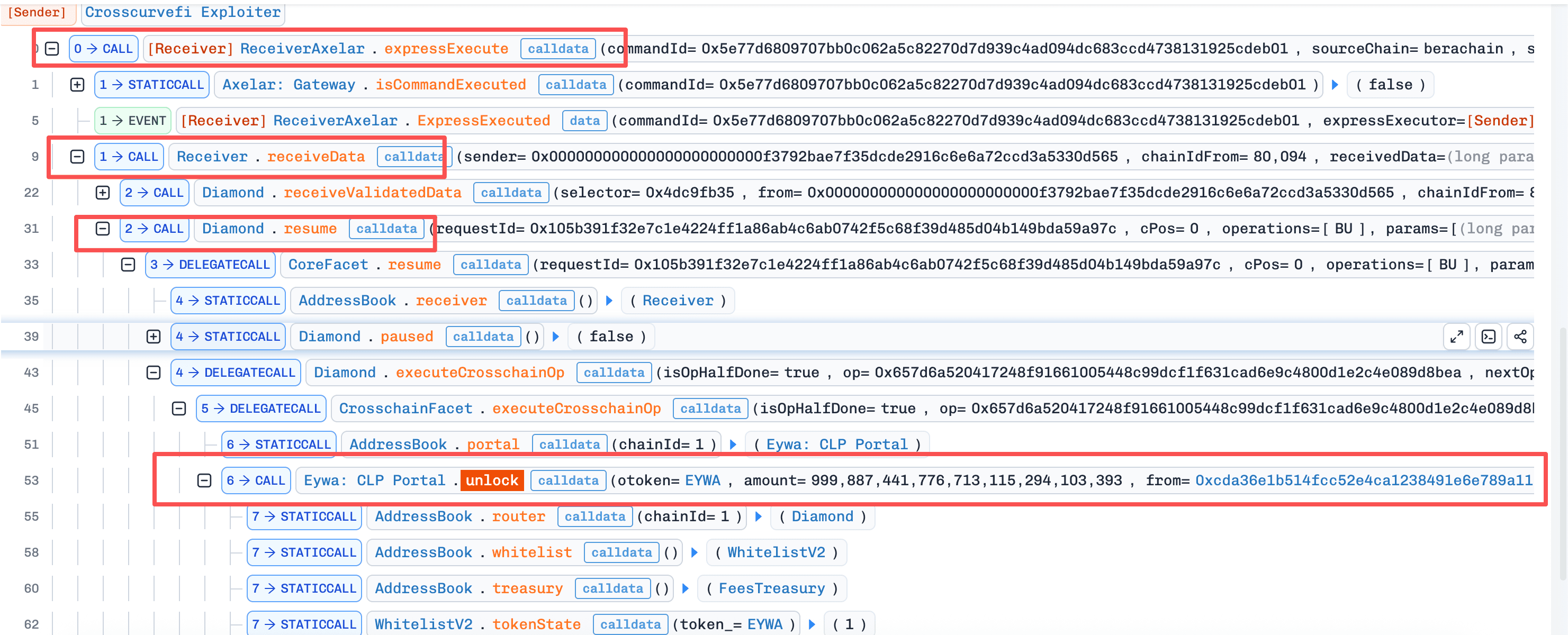

Step 1: The attacker directly invoked

expressExecute(), spoofing thesourceChain,sourceAddress, andpayload. SinceexpressExecute()bypasses Gateway validation and proceeds directly to_execute(), the only remaining security measure was a peer-address whitelist check:require(peers[sourceChain] == sourceAddress.toAddress()). This check was insufficient because bothsourceChainandsourceAddresswere externally supplied. By providing the correct whitelisted peer address, the attacker bypassed it. -

Step 2: The forged

payloadwas then forwarded to theReceiver.receiveData()branch. Theresume()function executed the cross-chain operationPortalV2.unlock()based on the malicious payload, resulting in the unauthorized unlocking of funds to the attacker.

Conclusion

This incident was fundamentally caused by insufficient access control on an accelerated execution path within a cross-chain receiver contract. By exposing expressExecute() as a permissionless function and relying solely on externally supplied peer information, CrossCurve effectively allowed attackers to bypass Axelar Gateway's security guarantees and execute arbitrary cross-chain payloads.

To mitigate similar risks in the future, cross-chain protocols integrating express or optimistic execution mechanisms should:

-

Enforce strict caller authentication on fast-path execution functions, ensuring only trusted relayers or gateways can invoke them.

-

Avoid relying on attacker-controlled metadata (such as source chain or address) as the sole basis for authorization.

-

Treat express execution as a privileged operation and apply defense-in-depth checks equivalent to standard validated execution paths.

Careful adherence to these principles is critical when designing cross-chain systems, where a single validation bypass can result in systemic asset loss across multiple networks.

2. GYD Incident

Brief Summary

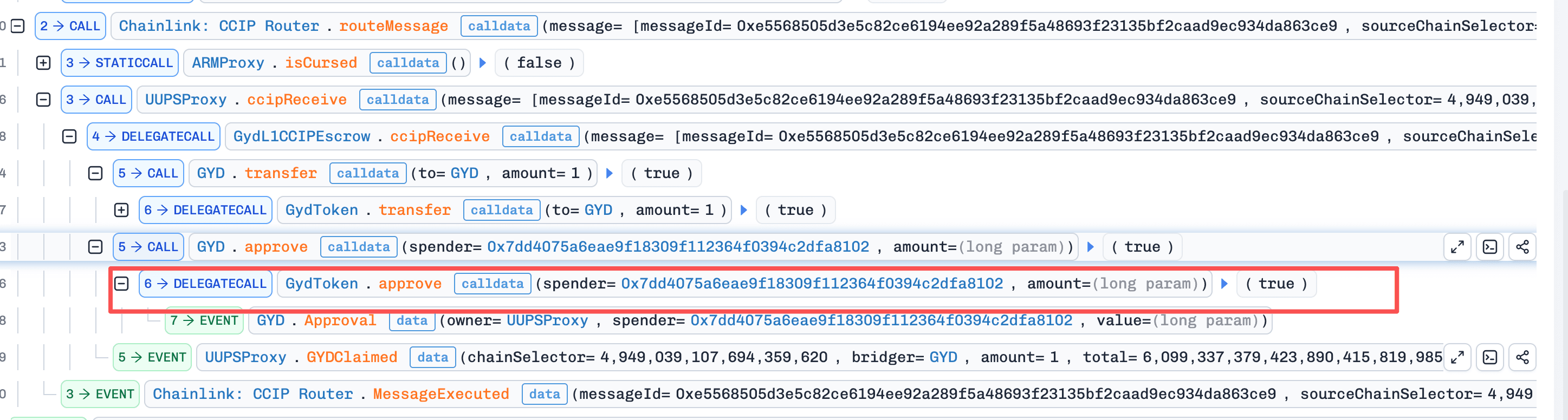

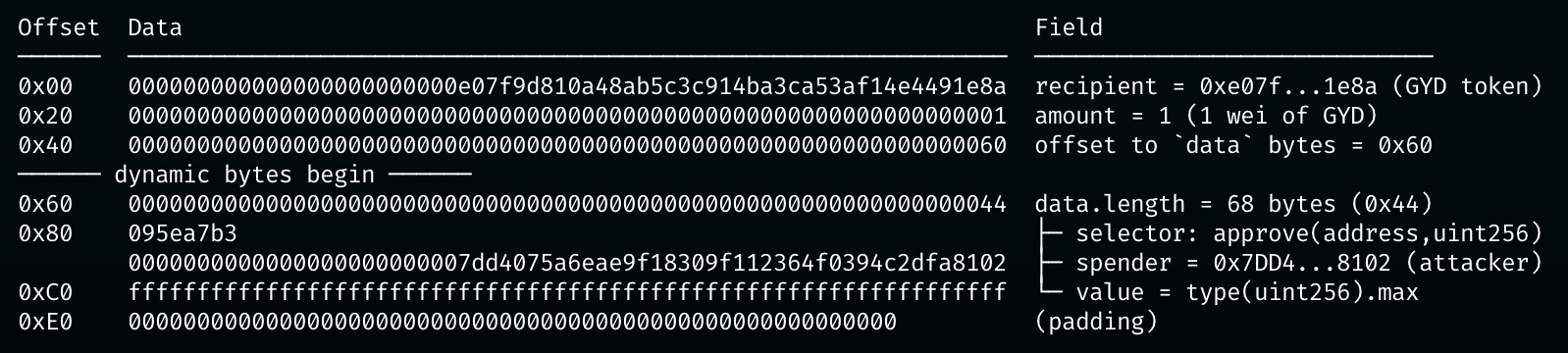

On February 3, 2026, the GYD Protocol was exploited, resulting in approximately $700K in losses. The root cause was that its CCIP receiver trusted attacker-controlled message data as execution context. The exploit was triggered by a CCIP message sent from Arbitrum, which was correctly authenticated at the messaging layer, but whose decoded payload was later used to perform arbitrary external calls in _ccipReceive(). By setting the decoded recipient to the GYD token contract and supplying calldata for approve(attacker, type(uint256).max), the escrow unintentionally granted unlimited allowance over its GYD balance. The attacker subsequently drained the funds via transferFrom().

Background

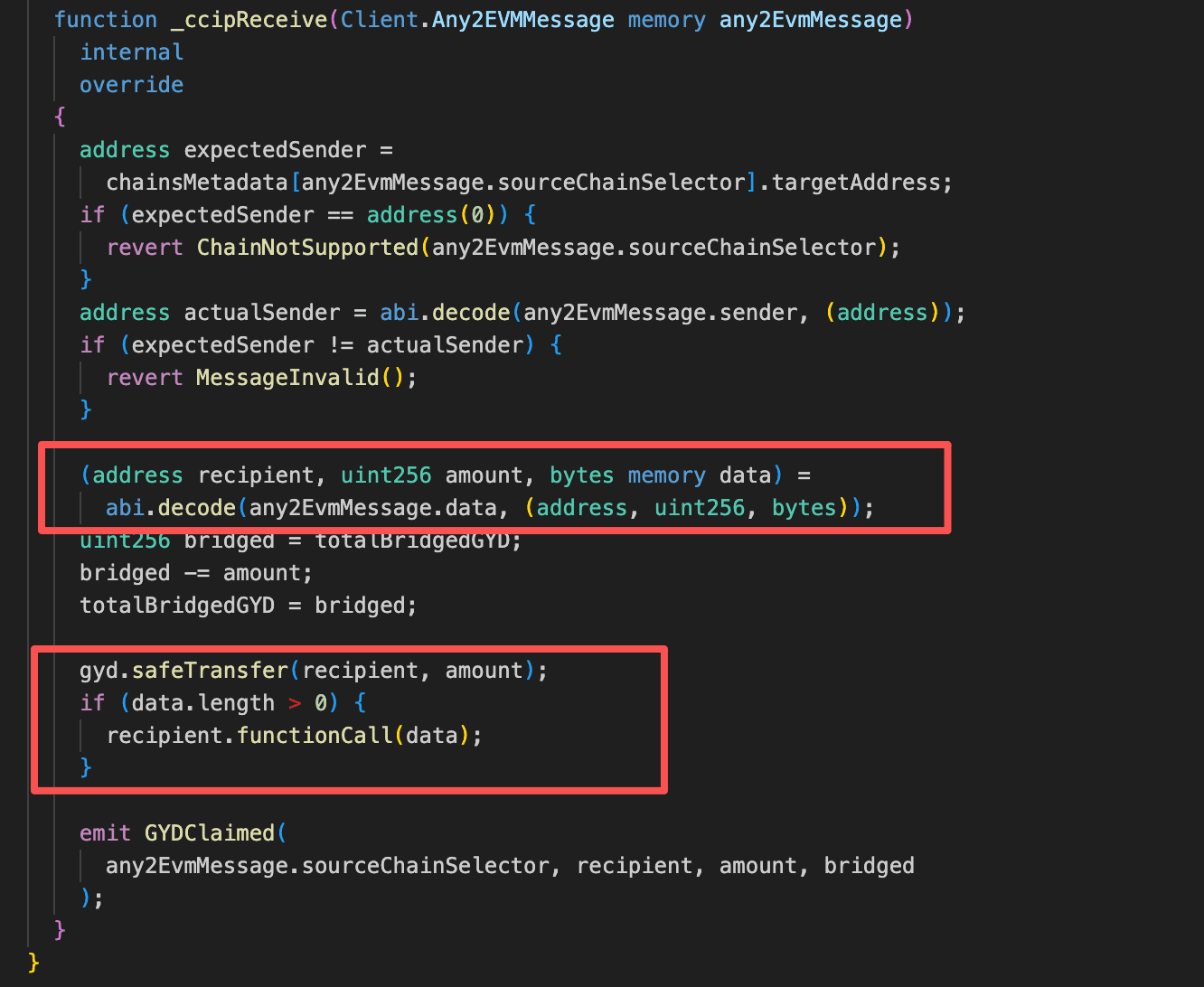

The GydL1CCipEscrow contract is a cross-chain asset escrow contract built on the Chainlink CCIP standard. Users lock GYD tokens in this contract on L1, which then sends a cross-chain message via CCIP to the destination chain. Conversely, when a cross-chain message arrives at the escrow, CCIP validates its authenticity and triggers _ccipReceive(). This function parses the incoming calldata to extract tx.recipient and data, executes GYD transfer or unlocking logic based on the parsed parameters (amount and recipient), and, if data is not empty, performs an arbitrary external call via recipient.functionCall(data).

Vulnerability Analysis

The core vulnerability is that GydL1CCipEscrow does not validate the tx.recipient address decoded from cross-chain messages. An attacker can set tx.recipient to the GYD token contract address and craft data as approve(attacker, type(uint256).max). Since the escrow contract holds a large amount of locked GYD tokens, this unrestricted external call causes the escrow to grant full allowance of its GYD tokens to the attacker, who can then drain all funds via transferFrom().

Attack Analysis

-

Step 1: The attacker initiated a malicious CCIP message on Arbitrum, specifying

tx.recipientas the GYD token contract address on Ethereum andtx.dataas the encoded calldata forapprove(attacker, type(uint256).max). -

Step 2: When the message was processed on Ethereum, the

_ccipReceive()function of theGydL1CCipEscrowcontract executed the approval on the GYD token contract without validatingtx.recipient. The attacker then calledtransferFrom()on the GYD token to drain all escrowed funds.

Conclusion

The root cause of this incident is that the GydL1CCipEscrow contract failed to validate the decoded payload when processing cross-chain messages, allowing an attacker to construct a malicious cross-chain call. For cross-chain bridge messaging, developers should:

-

Prohibit direct calls to token contracts from the escrow: Ensure that cross-chain message payloads cannot trigger calls to the escrowed token contract.

-

Implement an execution target whitelist: Restrict

tx.recipient(ortx.target) to a well-defined set of trusted addresses.

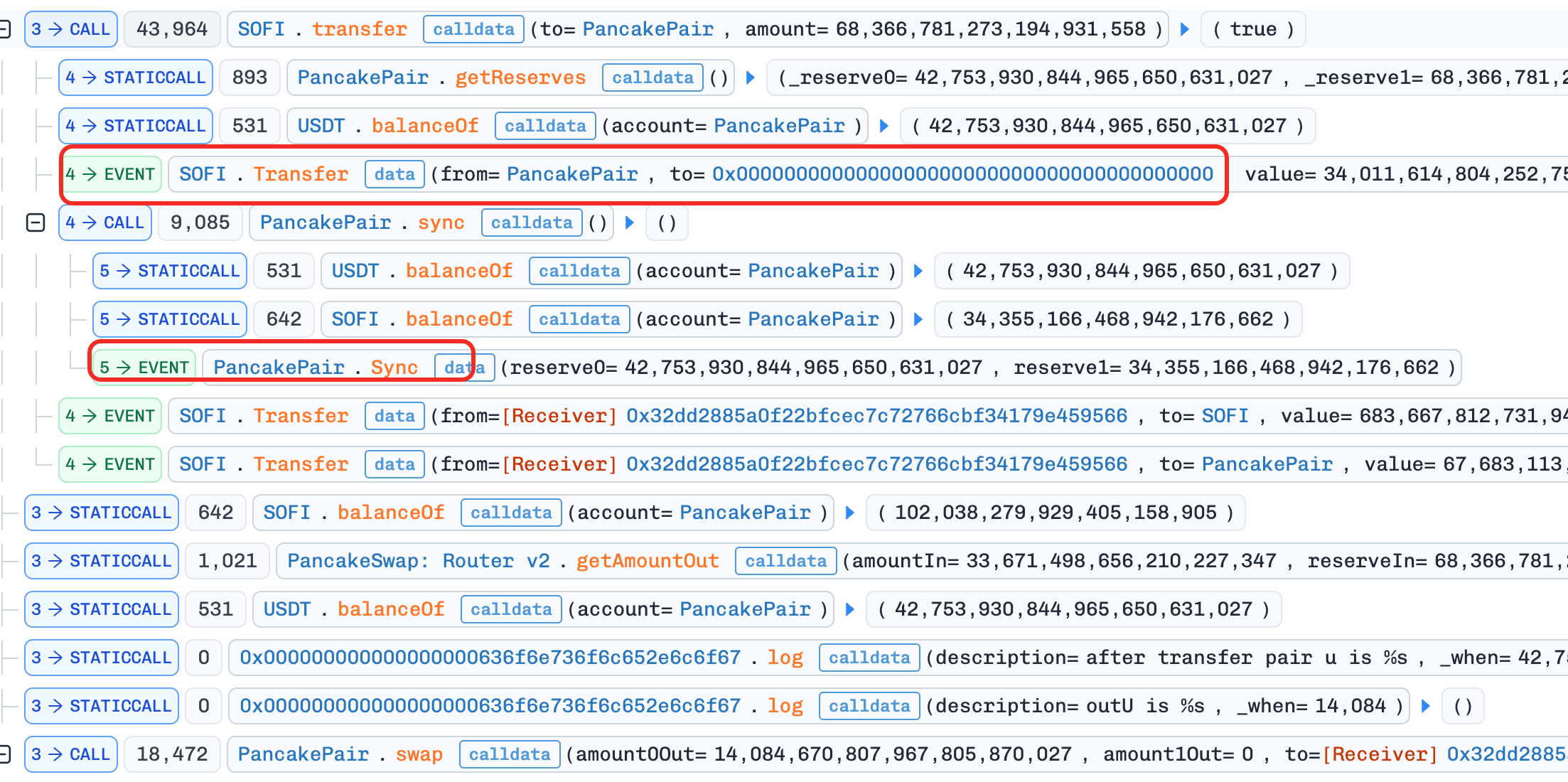

3. SOFI Token Incident

Brief Summary

On February 5, 2026, the SOFI token on the BNB Chain was exploited, resulting in approximately $29.6K in losses.

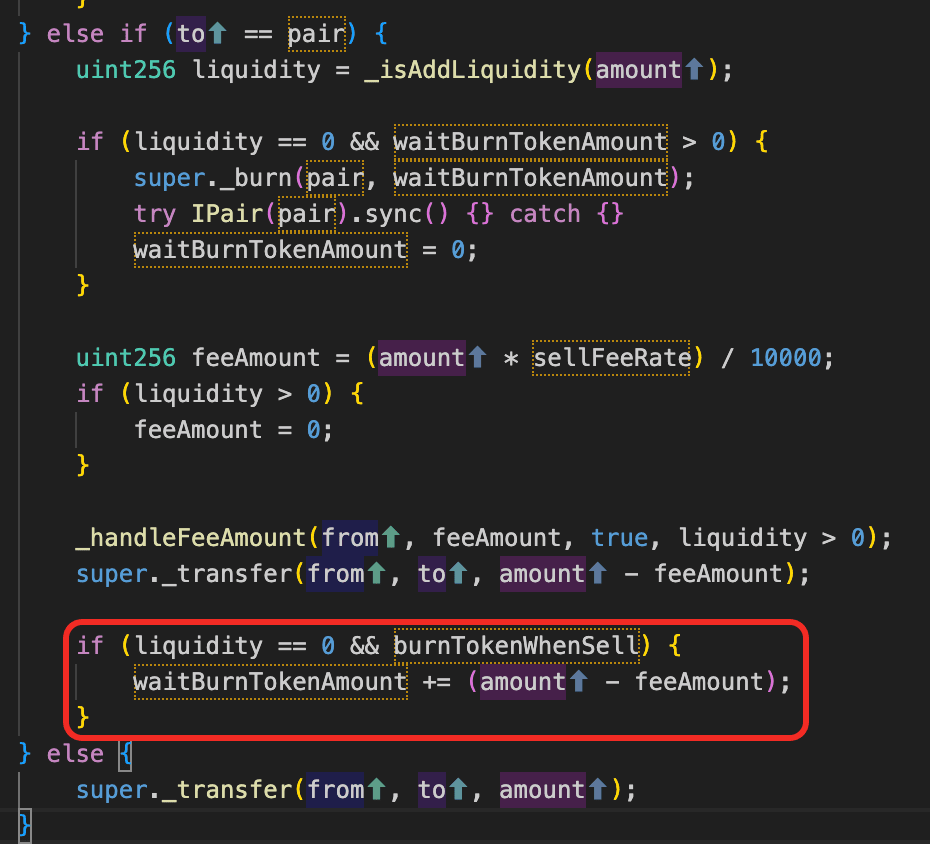

The root cause was a flawed burn mechanism implemented inside the token's overridden _transfer() function. By abusing the delayed burn logic that removed tokens directly from the PancakeSwap liquidity pool and triggered a subsequent sync(), the attacker was able to artificially inflate the SOFI price. Through repeated transfers and swaps, the attacker extracted excess USDT liquidity from the pool and repaid the flash loan with profit.

Background

SOFI is a custom ERC-20 token deployed on BNB Chain. Unlike a standard ERC-20 implementation, the SOFI token overrides the internal _transfer() function to embed additional logic related to burning tokens during sell operations.

The token is traded in a PancakeSwap-style constant-product AMM pool (SOFI–USDT). In such pools, the token price is derived from the ratio of token reserves. Any unexpected change to pool balances, especially those not caused by swaps, can directly manipulate the price.

In this design, the token contract itself interacts with the liquidity pool during transfers, making the pool's reserve accounting dependent on token-side logic rather than purely AMM mechanics.

Vulnerability Analysis

The vulnerability lies in SOFI's burn mechanism coupled with pool interaction inside _transfer().

When SOFI tokens are transferred to the liquidity pool address, the contract interprets the transfer as a sell and increments an internal accumulator variable waitBurnTokenAmount. However, the accumulated amount is not burned immediately. Instead, it is burned from the pool's balance on a subsequent transfer to the pool, after which the pool's sync() function is called.

This design introduces two critical issues:

-

Direct pool balance manipulation Burning tokens directly from the pool reduces the SOFI reserve without a corresponding USDT outflow, violating the AMM invariant and artificially increasing the SOFI price.

-

Delayed and attacker-controllable execution Because the burn only occurs on a future transfer, an attacker can precisely control when the burn and

sync()happen, allowing them to position themselves to profit from the price distortion.

As a result, the pool price no longer reflects genuine supply–demand dynamics, enabling extractable arbitrage.

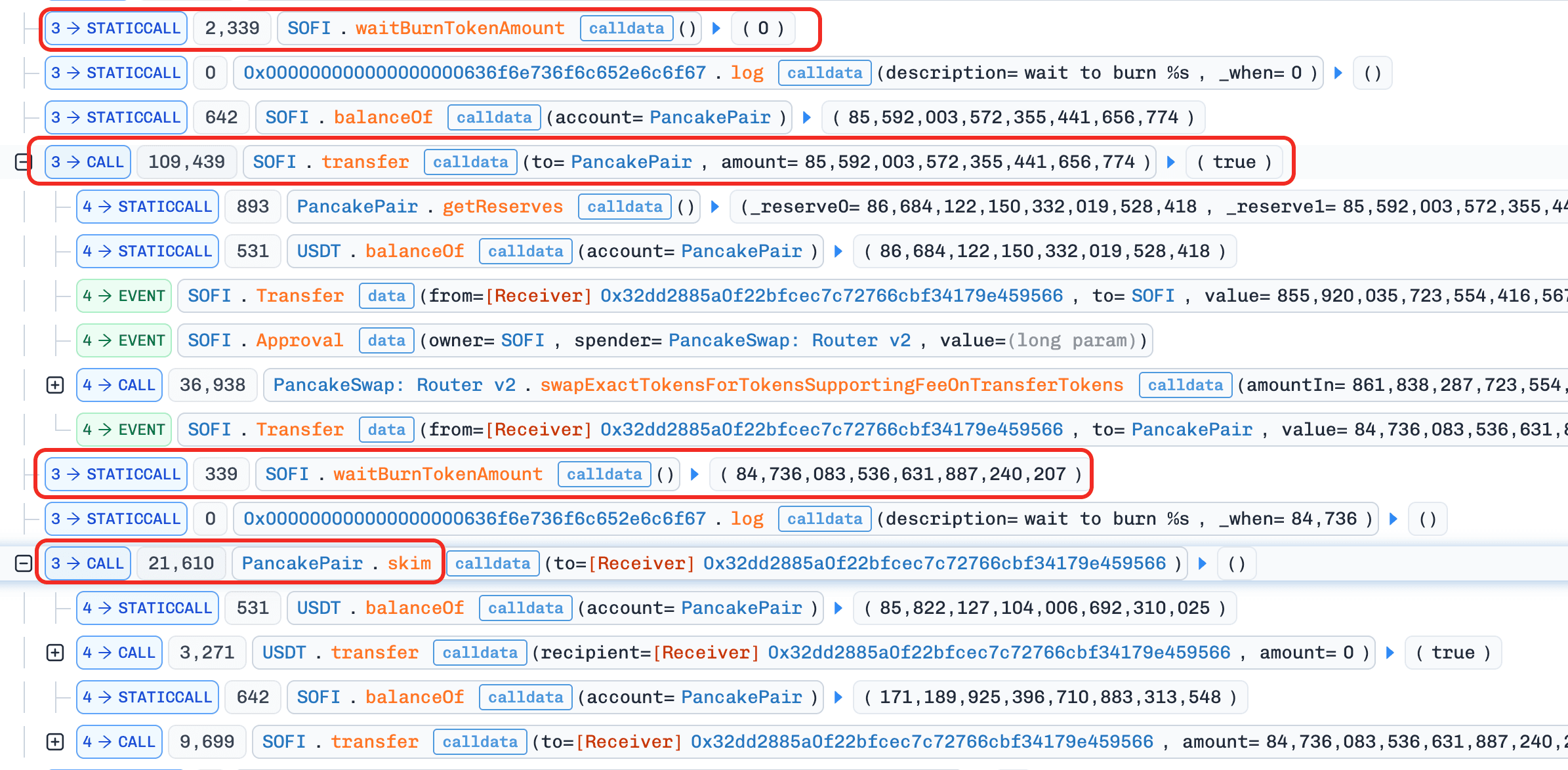

Attack Analysis

-

Step 1: Borrow

USDTvia a flash loan. -

Step 2: Swap

USDTforSOFIin theSOFI–USDTpool. -

Step 3: Transfer

SOFIinto the pool and invokeskim()to increasewaitBurnTokenAmountwith minimal loss. -

Step 4: Transfer

SOFIto the pool again to trigger burn +sync(), pushing theSOFIprice up, then swapSOFIforUSDT. -

Step 5: Repeat Step 4. The newly accumulated

waitBurnTokenAmountis only burned on the next transfer, so multiple iterations are required. -

Step 6: Drain

USDTfrom the pool, then repay the flash loan.

Conclusion

This incident was ultimately caused by an unsafe token-side burn mechanism that directly manipulated AMM pool balances. By embedding delayed burn logic inside _transfer() and executing burns from the liquidity pool itself, the SOFI token broke the fundamental assumptions of constant-product AMMs and enabled deterministic price manipulation.

For ERC-20 tokens that override _transfer(), developers should take special care to avoid:

-

Burning tokens directly from liquidity pools

-

Introducing delayed or stateful mechanisms that affect pool reserves

-

Coupling token logic too tightly with AMM internals

In general, tokenomics-related logic should never be allowed to arbitrarily alter pool balances, as even small deviations can be repeatedly exploited to drain liquidity.

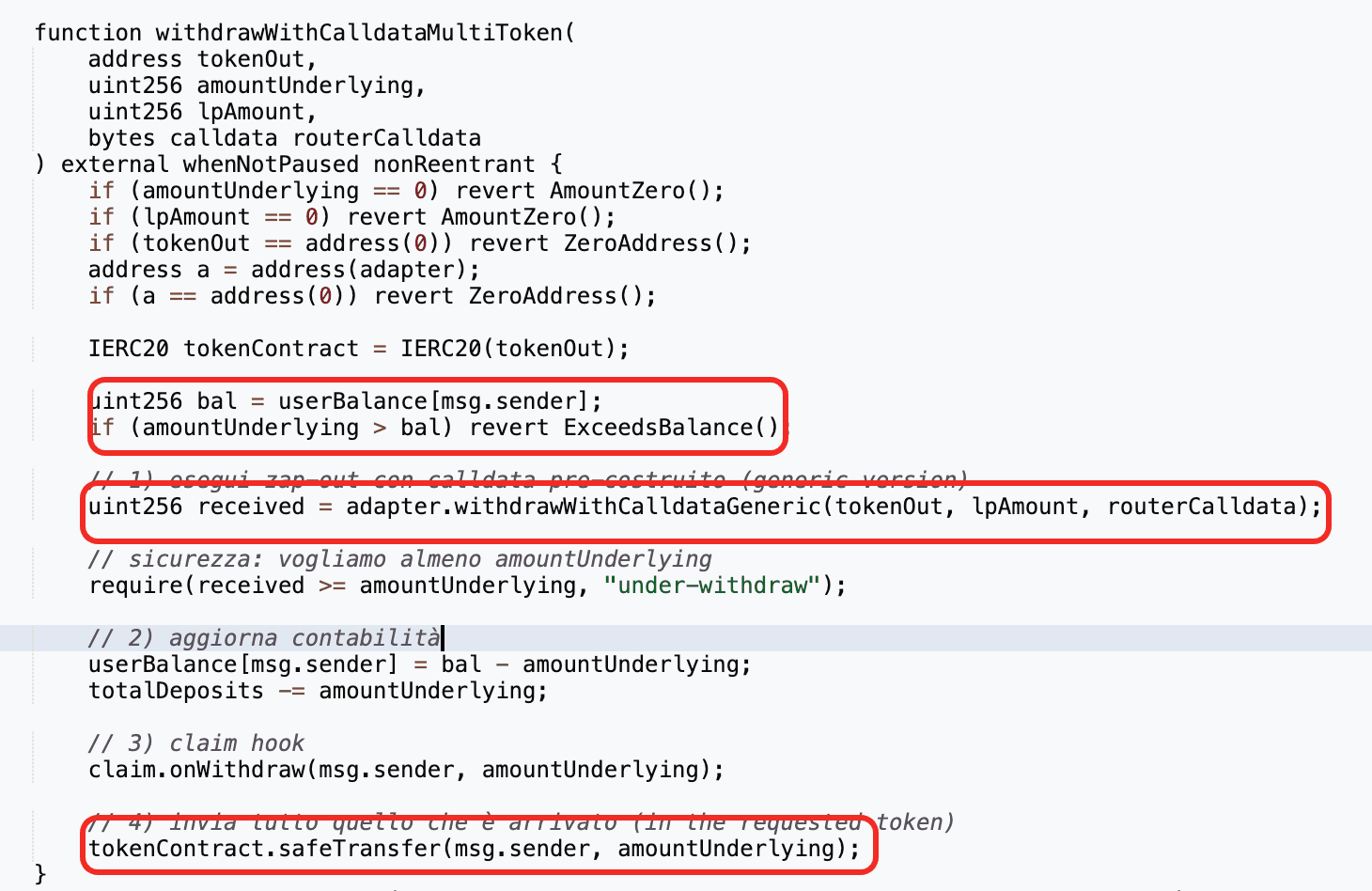

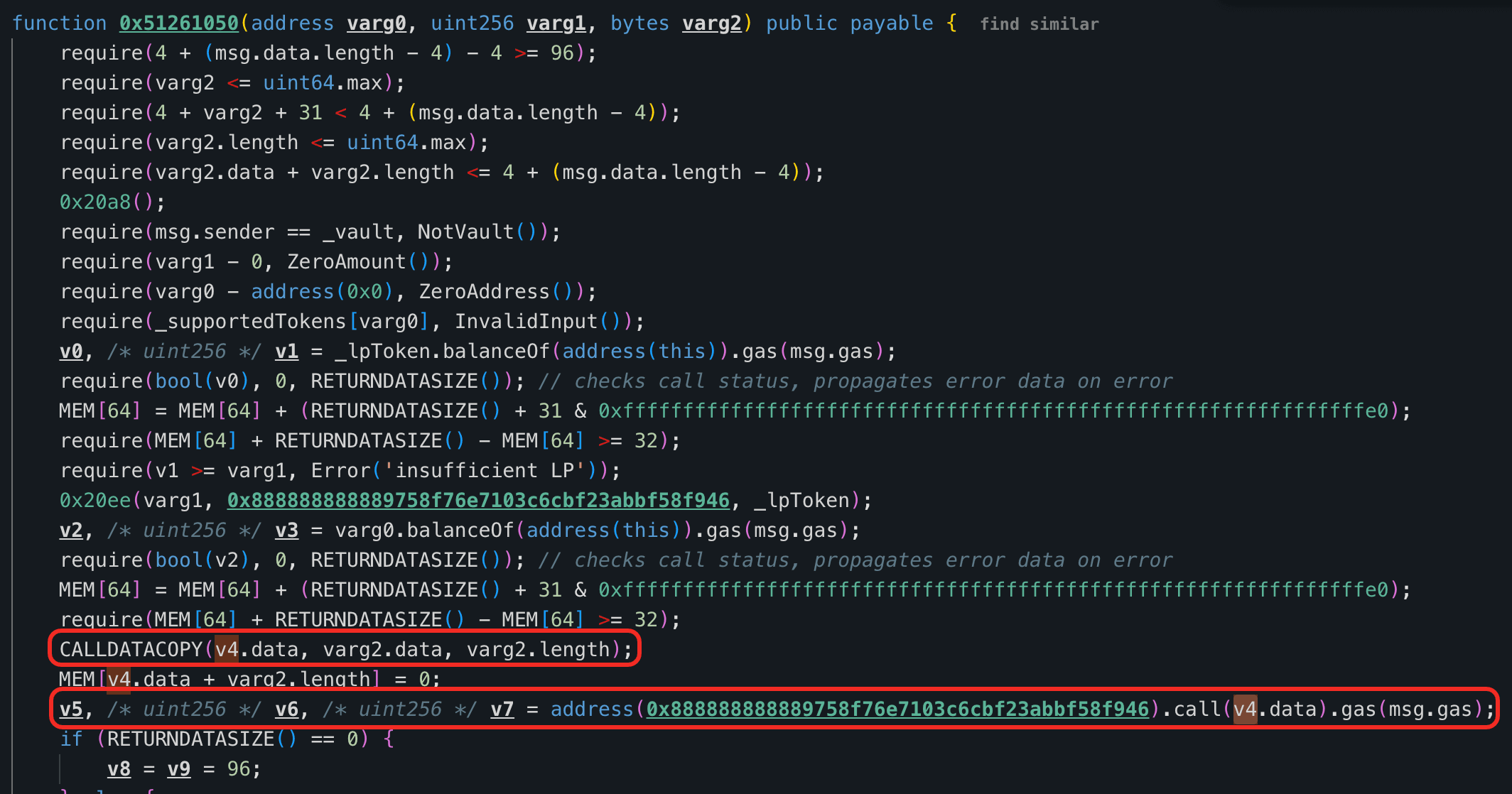

4. Unknown Staking Protocol Incident (Feb 5, 2026)

Brief Summary

On February 5, 2026, the Unknown Staking Protocol on Ethereum was exploited, resulting in approximately $71.6K in losses.

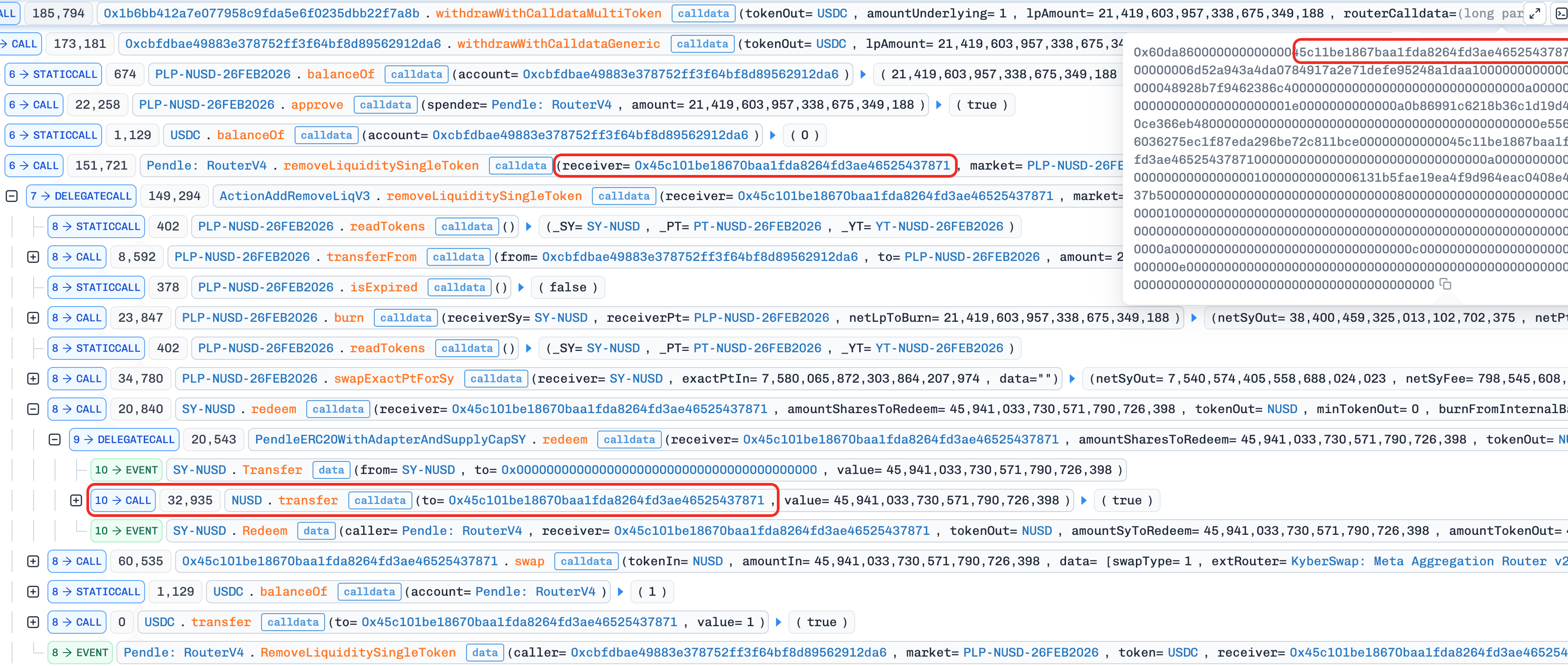

The root cause was the protocol's reliance on unverified, user-supplied input data during withdrawals. Specifically, the protocol forwarded attacker-controlled routerCalldata and LP amounts to the Pendle Router without validation. By crafting calldata that removed the protocol's entire LP position and setting themselves as the receiver, the attacker was able to drain all assets held by the vault.

Background

The Unknown Staking Protocol is a simple yield vault built on top of Pendle Finance. Users deposit assets into the vault, which then routes those assets through the Pendle Router to mint yield-bearing positions. Internally, deposits are converted into SY, split into PT and YT, and combined to form Pendle LP tokens.

The protocol custody-holds all LP tokens and maintains internal accounting of each user's deposited underlying amount. When users withdraw, the vault redeems LP tokens via the Pendle Router and returns the corresponding assets to the user.

Vulnerability Analysis

The root cause is unvalidated input data. The function withdrawWithCalldataMultiToken() takes four parameters: the underlying token, the underlying amount, the LP amount, and routerCalldata. It only checks whether the user's recorded underlying balance is sufficient, but does not validate the LP amount or the contents of routerCalldata. When removing liquidity via the Pendle Router, the contract relies entirely on parameters embedded in routerCalldata. As a result, an attacker could pass the protocol's full LP balance and set themselves as the receiver, draining all assets held by the protocol.

Attack Analysis

-

Step 1: Take a

USDCflash loan. -

Step 2: Deposit a small amount of

USDCinto the protocol, which routes funds through thePendle Routerto add liquidity and mint LP. -

Step 3: Invoke

withdrawWithCalldataMultiToken()with a craftedrouterCalldatathat sets thereceiverto the attacker and thelpAmountto the protocol's entire LP balance. -

Step 4: The protocol removes liquidity via the

Pendle Routerusing the attacker-controlled parameters and sends all assets to the attacker. -

Step 5: Swap the received assets back to

USDC, repay the flash loan, and keep the remainder as profit.

Conclusion

This incident was ultimately caused by blind trust in attacker-controlled external input within a critical withdrawal path. By forwarding arbitrary calldata and LP amounts to an external router without validation, the protocol allowed users to execute withdrawals far exceeding their entitled share, leading to complete drainage of the vault's Pendle position.

For production vaults and yield strategies, especially those integrating complex external routers, developers should:

-

Treat all user-supplied input, including calldata, as untrusted and validate it rigorously.

-

Derive sensitive parameters (such as LP amounts and receivers) internally, rather than accepting them from users.

-

Apply defense-in-depth by enforcing consistency between internal accounting and external execution results.

Failure to do so can allow even a single withdrawal call to compromise all assets held by the protocol.

5. LZMultiCall Protocol Incident

Brief Summary

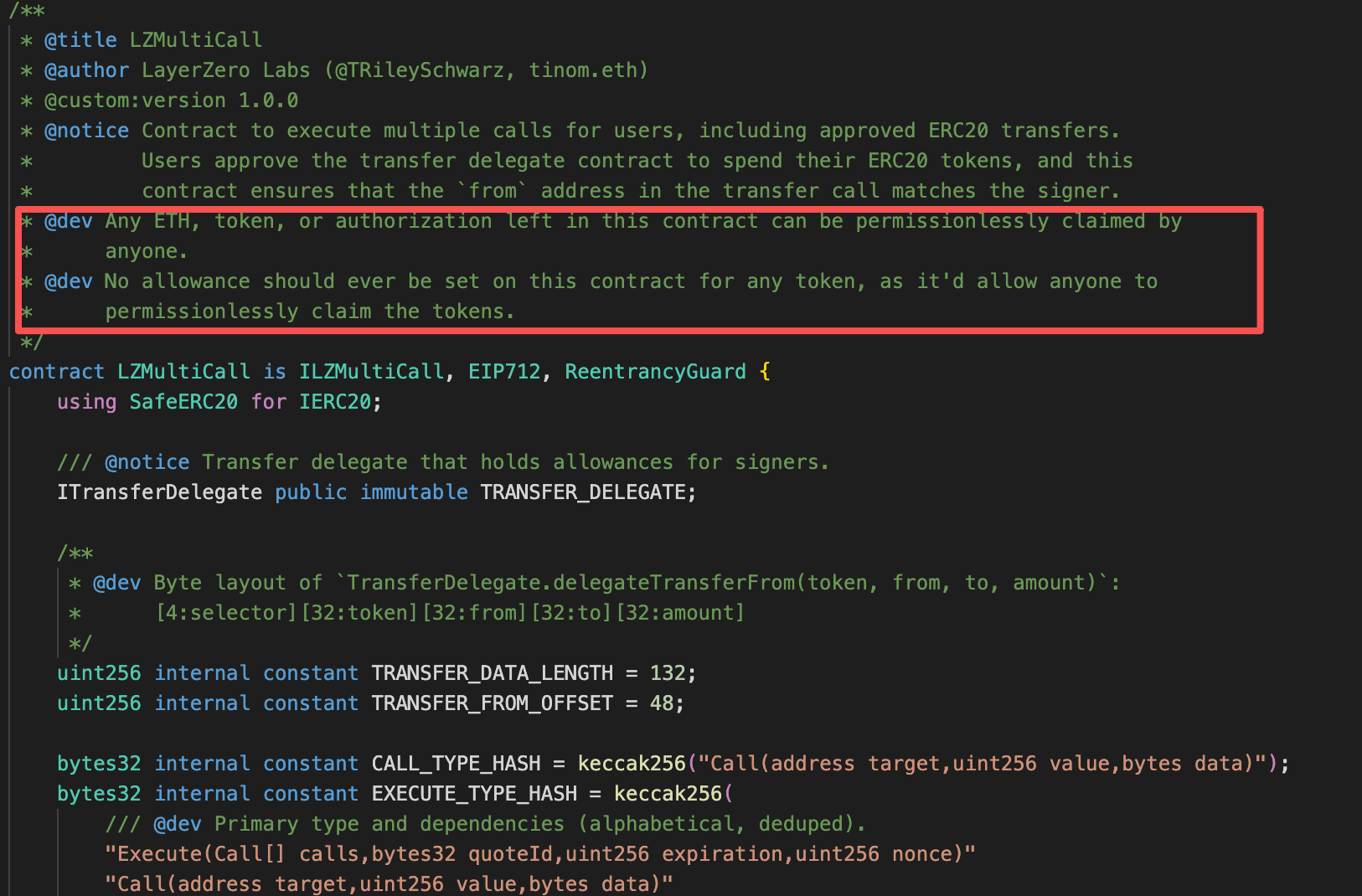

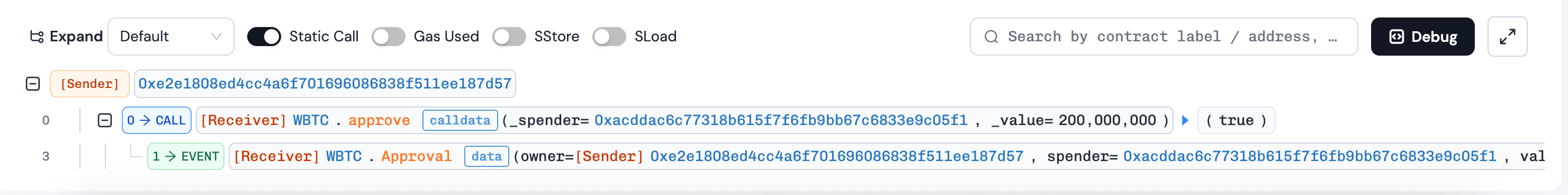

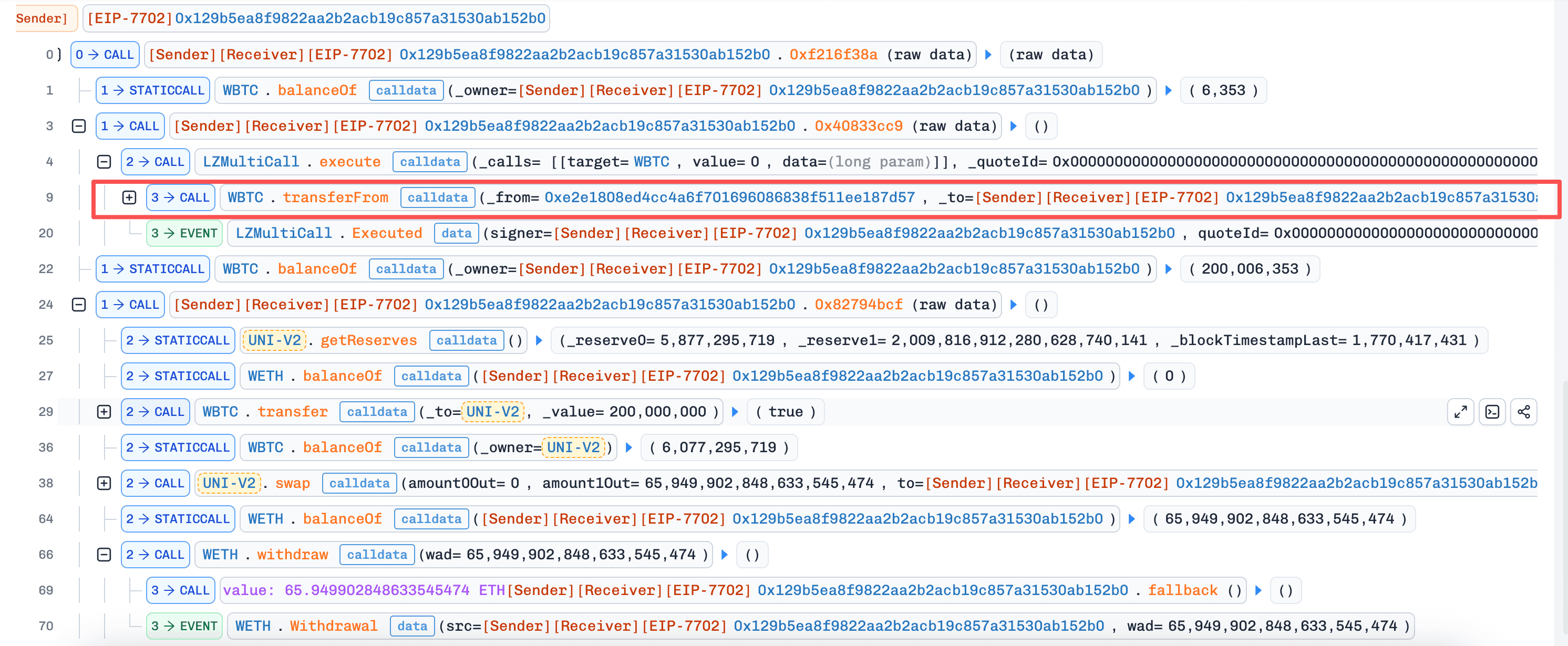

On February 7, 2026, the LZMultiCall incident resulted in approximately $142K in losses on Ethereum.

The incident was not caused by a vulnerability in the LZMultiCall contract itself, but by user misuse. LZMultiCall is a stateless batch execution contract that is not designed to custody assets or hold ERC-20 allowances. However, some users mistakenly approved token allowances to the contract. An attacker subsequently exploited these dangling approvals by invoking execute() with crafted calldata to call transferFrom(), draining tokens from the affected users.

Background

LZMultiCall is a generic batch execution utility contract. Its intended purpose is to allow users to bundle multiple calls into a single transaction, forwarding user-supplied calldata to target contracts.

Critically, LZMultiCall is designed to be stateless and non-custodial. It is not meant to hold assets, nor should users ever grant it ERC-20 allowances. Any token approvals granted to LZMultiCall violate its explicit usage assumptions and expose users to risk, since the contract can forward arbitrary calls on behalf of the caller.

Vulnerability Analysis

Although LZMultiCall functioned as designed, its permissionless execute() function became exploitable once users mistakenly granted it ERC-20 allowances. Because the contract forwards arbitrary calldata to any target, an attacker could invoke execute() with calldata encoding transferFrom(victim, attacker, amount) on token contracts, effectively draining any outstanding allowances.

Attack Analysis

- The attacker invoked

execute()with crafted calldata targeting the token contract, usingtransferFrom()to transfer tokens from users who had mistakenly approved allowances toLZMultiCall.

Conclusion

This incident was ultimately caused by violating the explicit usage assumptions of a stateless batch execution contract. LZMultiCall was never intended to custody funds or hold ERC-20 allowances. Once users mistakenly granted approvals, the contract's permissionless execution model allowed any caller to drain those allowances through arbitrary forwarded calls.

For users and integrators interacting with batch execution or multicall-style contracts:

-

Never grant ERC-20 allowances to contracts that are not explicitly designed to custody assets.

-

Treat generic call-forwarding contracts as untrusted execution surfaces.

-

Prefer per-transaction approvals or allowance-free designs (e.g.,

permit) where possible.

Even in the absence of a protocol vulnerability, misunderstanding a contract's trust model can result in significant and irreversible losses.

6. Unknown Protocol Incident (Feb 8, 2026)

Brief Summary

On February 8, 2026, the Unknown Protocol on Ethereum was exploited, resulting in approximately $63K in losses.

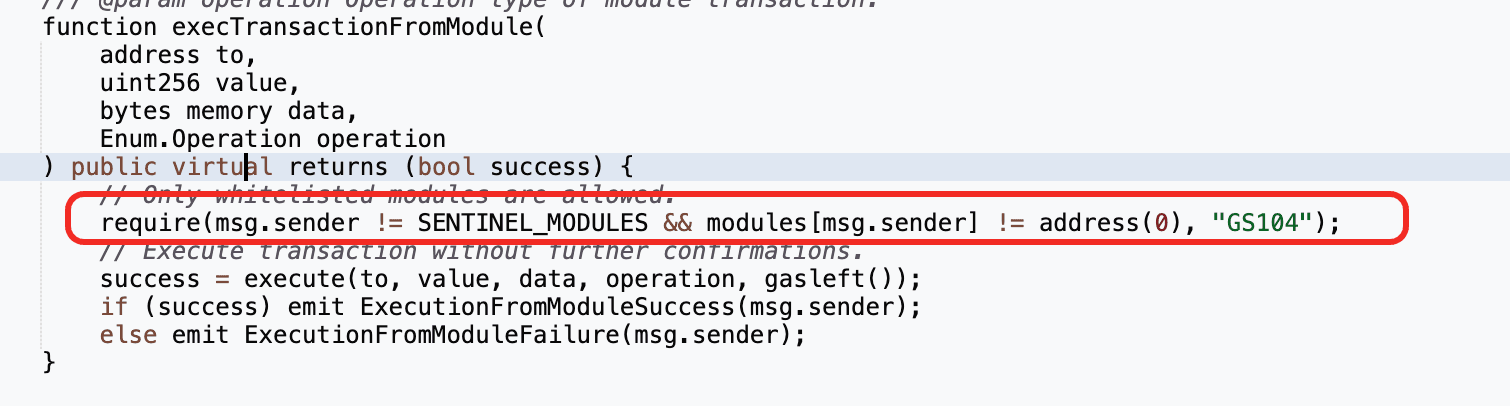

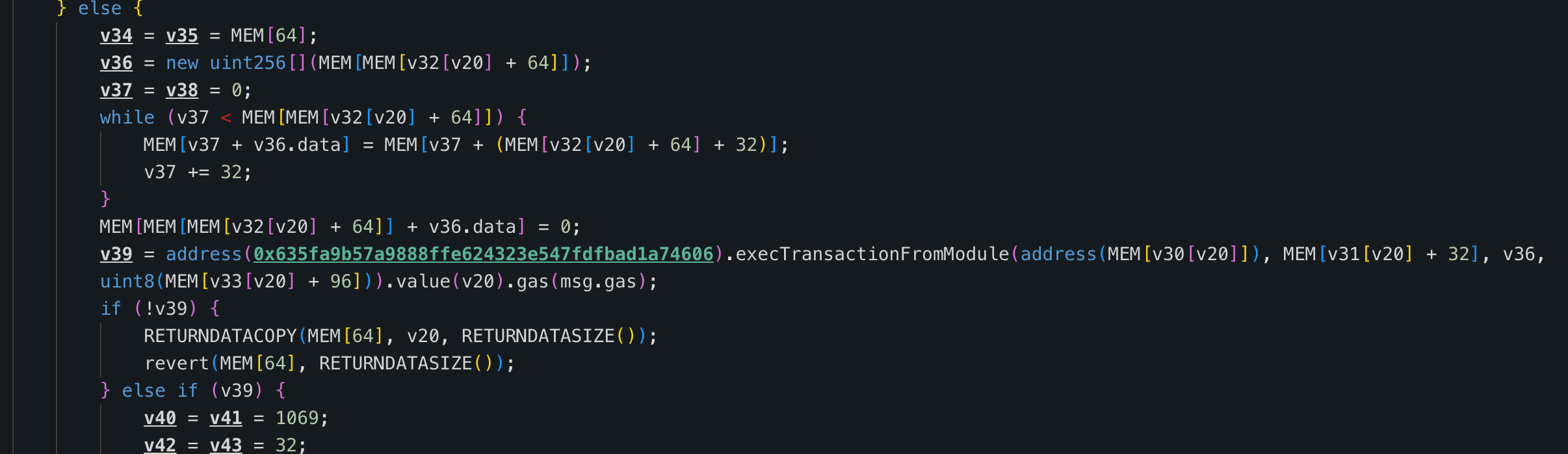

The root cause was unverified attacker-controlled input data in a Gnosis Safe module execution path. A utility contract (0xF5E4) registered as a SafeModule exposed a flashloan callback that decoded arbitrary user-supplied data and directly invoked GnosisSafe.execTransactionFromModule(). Because module-originated calls bypass signature verification by design, the attacker was able to execute arbitrary Safe-authorized transactions, repay the Safe's Aave V3 debt, and withdraw all collateral to attacker-controlled addresses.

Background

The protocol architecture centers around a Gnosis Safe that manages a leveraged position on Aave V3. Gnosis Safe supports a modular execution model, where designated SafeModules are allowed to execute transactions on behalf of the Safe without requiring owner signatures. This design is intended to support automation, integrations, and advanced strategies.

In this setup, contract 0xF5E4 was configured as a SafeModule of the Gnosis Safe. The contract appears to be a helper utility designed to support flashloan-based position management. It implements a flashloan callback, receiveFlashLoan(), which is invoked by external liquidity providers during flashloan execution.

Because module calls bypass signature verification, the correctness and safety of module logic is critical: any flaw effectively grants unrestricted control over the Safe.

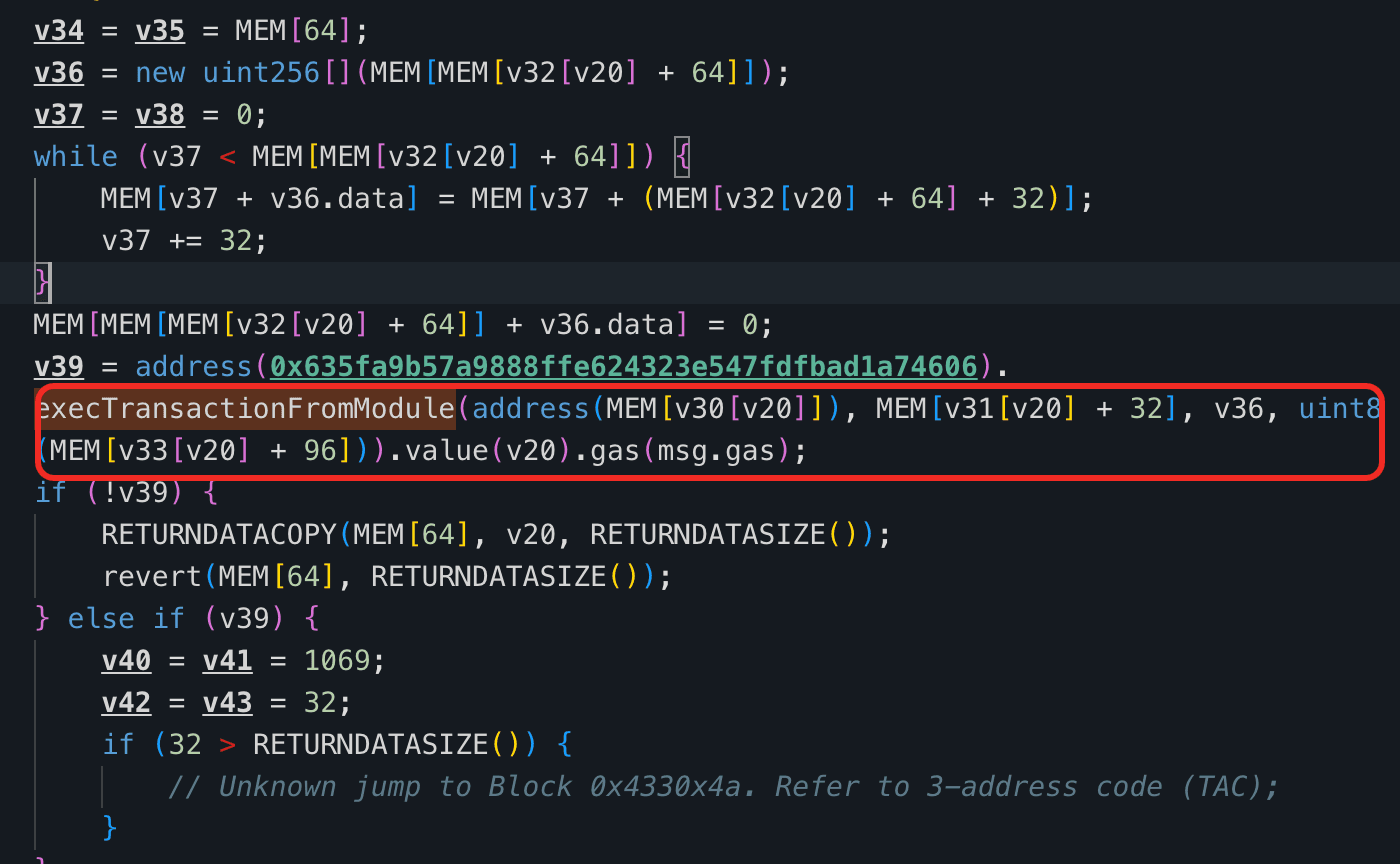

Vulnerability Analysis

The SafeModule 0xF5E4 exposes a flashloan callback receiveFlashLoan() that decodes externally supplied userData and uses it directly to call GnosisSafe.execTransactionFromModule(). Because 0xF5E4 is registered as a SafeModule, calls originating from it bypass signature verification. However, receiveFlashLoan() does not authenticate the caller or validate the decoded parameters (e.g., target address, value, calldata, or operation type). As a result, an attacker can supply crafted userData to make the module execute arbitrary transactions via the Safe, enabling them to repay the Safe’s Aave V3 debt, withdraw all collateral, and drain the position for profit.

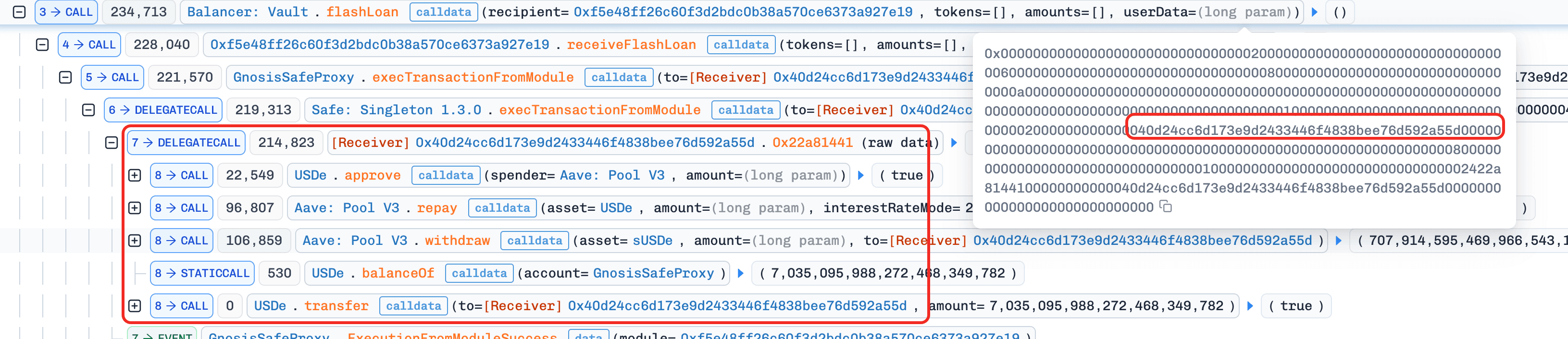

Attack Analysis

-

Step 1: The attacker took a flashloan via Uniswap V4 and transferred the funds to the

GnosisSafe. -

Step 2: The attacker called Balancer's

flashLoan()with crafteduserData, borrowing no actual assets, and setting therecipientto0xF5E4. -

Step 3: In

0xF5E4.receiveFlashLoan(), the contract decoded the attacker-supplieduserData. Since0xF5E4is registered as a Safe module, it bypassed signature checks and invokedexecTransactionFromModule()to execute arbitrary calls as dictated by the parameters embedded inuserData. -

Step 4: Using this capability, the attacker repaid the

GnosisSafe's debt on Aave V3 and withdrew all collateral, thereby realizing profit.

Conclusion

This incident was ultimately caused by unsafe use of module-based execution combined with unvalidated external input. By forwarding arbitrary, attacker-supplied userData to execTransactionFromModule(), the SafeModule 0xF5E4 effectively exposed unrestricted control over the Gnosis Safe. Since Safe modules bypass signature checks by design, this flaw enabled a complete compromise of the Safe's Aave V3 position.

For systems that rely on Gnosis Safe modules or similar privileged execution frameworks, developers should:

-

Treat all external input, including flashloan

userData, as untrusted and validate it rigorously. -

Restrict module execution to a well-defined set of actions, targets, and selectors.

-

Avoid generic "utility" modules that forward arbitrary calldata to privileged execution functions.

Failure to enforce these safeguards can transform a single helper contract into a full administrative backdoor.

About BlockSec

BlockSec is a full-stack blockchain security and crypto compliance provider. We build products and services that help customers to perform code audit (including smart contracts, blockchain and wallets), intercept attacks in real time, analyze incidents, trace illicit funds, and meet AML/CFT obligations, across the full lifecycle of protocols and platforms.

BlockSec has published multiple blockchain security papers in prestigious conferences, reported several zero-day attacks of DeFi applications, blocked multiple hacks to rescue more than 20 million dollars, and secured billions of cryptocurrencies.

-

Official website: https://blocksec.com/

-

Official Twitter account: https://twitter.com/BlockSecTeam