Introduction

Stablecoins have seen rapid growth in recent years. As a result, regulators increasingly emphasize the need for mechanisms that allow freezing of illicit funds. We observe that major stablecoins, such as USDT and USDC, already incorporate such capabilities. In practice, there have been numerous cases where funds linked to money laundering and other illegal activities were successfully frozen.

Moreover, our research indicates that stablecoins are not only used in money laundering, but are also frequently employed in the financing of terrorist organizations. Therefore, this blog aims to examine the issue from two perspectives. First, we systematically analyze USDT transactions that have been frozen. Second, we investigate how frozen funds are related to terrorist financing.

Disclaimer: This analysis is based solely on publicly available data and may contain inaccuracies. If you have any comments or corrections, please contact us at [email protected].

USDT Blocked Addresses Analysis

Data Collection

Our methodology for identifying and tracking blacklisted Tether addresses is based on direct on-chain event monitoring. The process, confirmed through Tether's smart contract source code, is as follows:

- Event identification: We determined that Tether's smart contract manages its blacklist by emitting two specific events: AddedBlackList when an address is added, and RemovedBlackList when an address is removed.

- Dataset construction: The extracted data is used to build a comprehensive time-series dataset. For each blacklisted address, we record the following fields: the address itself, the blacklisting timestamp (blacklisted_at), and, if applicable, the unblacklisting timestamp (unblacklisted_at) for its removal.

function addBlackList (address _evilUser) public onlyOwner {

isBlackListed[_evilUser] = true;

AddedBlackList(_evilUser);

}

function removeBlackList (address _clearedUser) public onlyOwner {

isBlackListed[_clearedUser] = false;

RemovedBlackList(_clearedUser);

}

event AddedBlackList(address indexed _user);

event RemovedBlackList(address indexed _user);Findings

Our analysis of Tether (USDT) data on the Ethereum and Tron blockchains reveals a striking trend. Since 1 Jan. 2016, a total of 5,188 addresses have been blacklisted, resulting in the freezing of assets worth over $2.9 billion.

Between June 13–30, 2025, alone, 151 addresses were blacklisted—90.07% of which were on the Tron network (List of addresses). The total value frozen during this short period reached a staggering $86.34 million.

- Temporal distribution of blacklisting events: Peaks in blacklisting activity were observed on June 15, 20, and 25, with June 20 seeing the highest number: 63 addresses blacklisted in a single day.

- Frozen asset distribution across addresses: The top 10 addresses with the largest frozen balances collectively hold $53.45 million, accounting for 61.91% of the total. The average frozen amount ($571.76K) is significantly higher than the median ($40.01K), indicating a skewed distribution where a few high-value addresses dominate, while most have relatively small frozen balances.

- Lifetime value distribution: The total historical inflows to these addresses amount to $807.76 million, of which $721.43 million was sent out prior to enforcement, and $86.34 million was frozen. This suggests that the majority of funds were likely moved before blacklisting occurred. Notably, 17% of the blacklisted addresses had no outbound transactions, hinting at possible use as temporary storage or aggregation points—warranting further scrutiny in future investigations.

- Newly created accounts are most likely to be blacklisted: Among all blacklisted addresses, 41% were newly created (with < 30 days of activity), 27% showed mid-term activity (91–365 days), and only 3% had long-term usage histories (≥ 730 days). This indicates that newly established accounts are disproportionately targeted.

- Most accounts achieve a “pre-freeze exit”: Around 54% of blacklisted addresses had already transferred out the majority of their funds (defined as lifetime outflows ≥ 90% of total inflows) before blacklisting. Additionally, 10% held a zero balance at the time of being frozen. These patterns suggest that enforcement actions often catch only the residual value of illicit flows, with most assets already laundered or moved.

- High laundering efficiency among new accounts: A FlowRatio vs. DaysActive scatter plot reveals that newer accounts not only dominate in quantity and blacklist frequency but also demonstrate the highest laundering efficiency, effectively transferring funds out before detection and enforcement.

Following the Money

MetaSleuth empowered our investigation by enabling the tracing of the 151 Tether-blacklisted addresses, which were blocked by USDT between June 13 to June 30, through which we identified both the key funders and end destinations associated with these addresses.

Where the Funds Came From

- Internal Contamination (91 addresses): A significant portion of the addresses received funds from other blacklisted addresses, indicating a highly interconnected laundering network.

- Fake Phishing Tags (37 addresses): Many upstream sources were labeled as “fake phishing” on MetaSleuth, suggesting the use of deceptive tagging tactics to obscure illicit activity and evade detection.

- Exchange Hot Wallets (34 addresses): Fund sources included known exchange hot wallets—Binance (20), OKX (7), and MEXC (7)—implying that inflows may have originated from compromised accounts or mule wallets in centralized exchanges.

- Single Dominant Distributor (35 addresses): A single blacklisted address appeared repeatedly as an upstream source, likely functioning as a central fund aggregator or mixer to distribute illicit assets.

- Cross-Chain Entry Points (2 addresses): Some funds originated from cross-chain bridges, suggesting that inter-chain laundering mechanisms were also leveraged in the fund flow.

Where the Funds Went

- To Other Blacklisted Addresses (54): This pattern reinforces the existence of an internal laundering loop within the network.

- To Centralized Exchanges (41): Funds were off-ramped through deposit addresses on centralized exchanges, including Binance(30), Bybit (7), and others.

- To Cross-Chain Bridges (12): Indicates attempts to launder assets beyond the TRON ecosystem, leveraging cross-chain transfer mechanisms.

Notably, exchanges such as Binance and OKX appear on both ends of the transaction flow—as sources of inflow (via hot wallets) and as destinations for outflow (via deposit addresses)—underscoring their central role in fund movement. The combination of ineffective AML/CFT enforcement and delays in asset freezing may have enabled illicit transfers to occur before regulatory actions could take effect.

We recommend that cryptocurrency exchanges, as key on- and off-ramps, adopt more robust monitoring, detection, and blocking mechanisms to proactively mitigate such risks.

Terrorist Financing Analysis

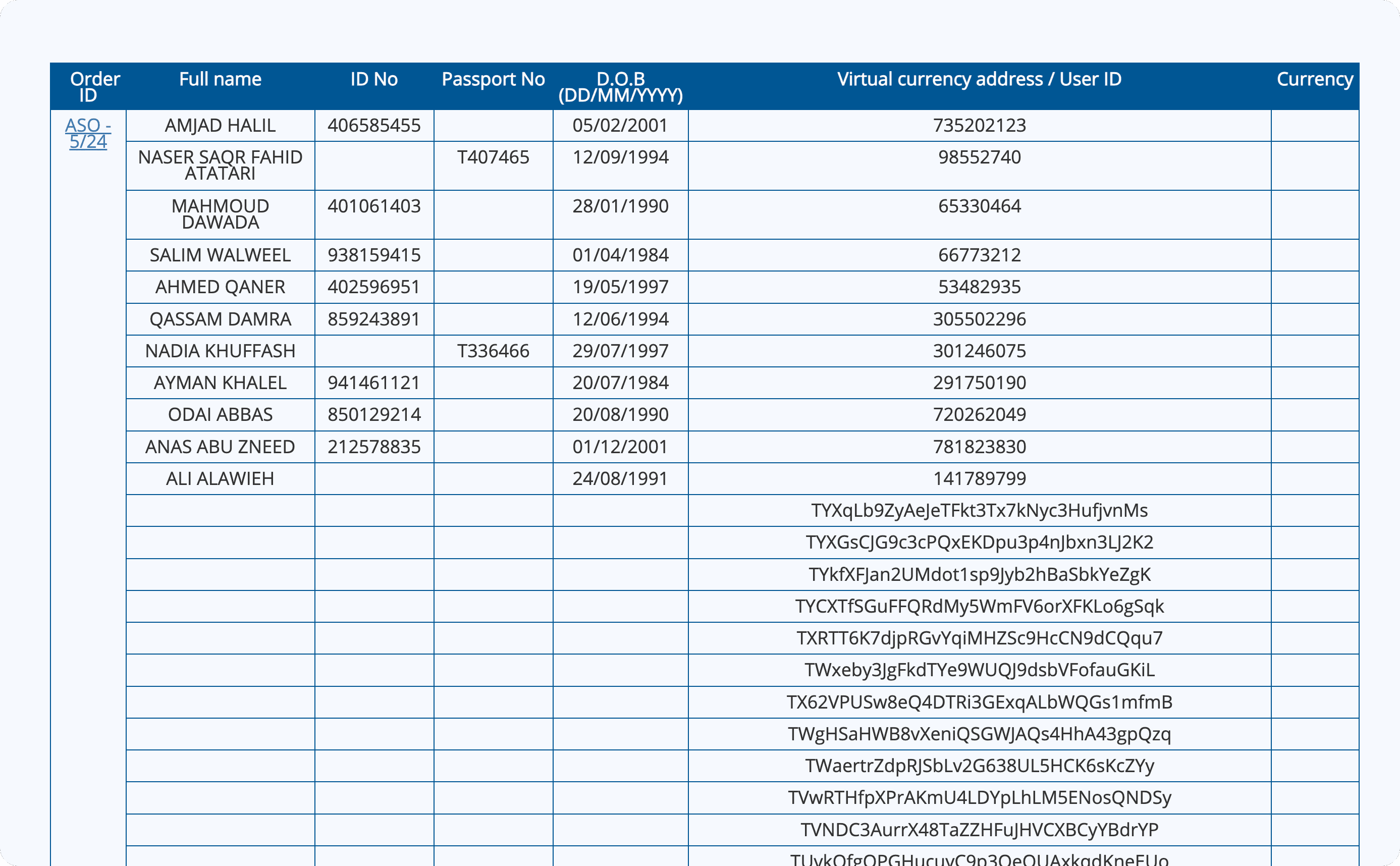

To gain deeper insights into USDT activities potentially linked to terrorist financing, we examined official documents—specifically, the Administrative Seizure Orders issued by Israel’s National Bureau for Counter Terror Financing (NBCTF). While we acknowledge that no single data source provides a complete picture, we use this dataset as a representative case study to understand a conservative lower bound of the USDT potentially involved in terrorist financing.

Findings

Our review of the NBCTF publications revealed several key findings:

- Timing of Seizure Orders: Only one new seizure order has been issued since the escalation of Israeli-Iranian Conflicts on June 13, 2025, dated June 26. Prior to that, the most recent order was issued on June 8, indicating a noticeable delay despite rising tensions.

- Frequency and Targeting Since October 7, 2024: Since the outbreak of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, eight seizure orders have been released. Among these, four explicitly identify "Hamas" as the target, while only one—the most recent—mentions "Iran".

- Scope of Targeted Assets: The combined orders targeted a wide range of assets, including:

- 76 USDT (Tron) addresses

- 16 BTC addresses

- 2 Ethereum addresses

- 641 Binance accounts

- 8 OKX accounts

Our on-chain investigation of the 76 USDT Tron addresses revealed a crucial operational insight regarding Tether’s response relative to the NBCTF seizure orders. Two distinct patterns emerged:

- Proactive Blacklisting:Tether had already blacklisted 17 Hamas-linked addresses prior to the public release of the corresponding seizure orders. These preemptive actions occurred, on average, 28 days in advance, with the earliest instance taking place 45 days before the official publication.

- Rapid Reaction: For the remaining addresses not already on the blacklist at the time of public disclosure, Tether responded promptly. The average time-to-blacklist following a seizure order was 2.1 days, demonstrating a rapid operational turnaround in response to official mandates.

These findings suggest a close and, in some cases, preemptive collaboration between stablecoin issuers (Tether) and law enforcement agencies—challenging the common perception that cryptocurrencies function entirely outside the scope of regulatory and security oversight.

Conclusion and AML/CFT Challenges

Our investigation reveals that stablecoins like USDT offer powerful tools for transaction transparency and control, they also pose emerging challenges for anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorism financing (CFT) enforcement. The presence of interconnected laundering loops, cross-chain obfuscation, delayed enforcement actions, and exploitation of centralized exchanges highlights systemic vulnerabilities in the current compliance ecosystem.

Several key challenges stand out:

- Reactive vs. Proactive Enforcement: While Tether demonstrated both proactive and reactive blacklisting behavior, most AML/CFT actions still rely on ex-post measures, allowing illicit actors to move significant funds before intervention.

- Exchange Blind Spots: Centralized exchanges remain a critical part of the laundering pipeline, often appearing as both entry and exit points. Insufficient monitoring or slow response times at these gateways allow suspicious flows to continue largely unhindered.

- Cross-Chain Laundering Complexity: The use of bridges and multi-chain infrastructure complicates traceability, as illicit actors increasingly exploit less-regulated ecosystems and bridge-based obfuscation to bypass compliance checks.

To address these issues, we recommend that ecosystem participants—particularly stablecoin issuers, exchanges, and regulators—enhance collaborative intelligence sharing, invest in real-time behavioral analytics, and implement cross-chain compliance frameworks. Only through timely, coordinated, and technically sophisticated AML/CFT efforts can we effectively safeguard the legitimacy and security of the stablecoin ecosystem.

BlockSec's Efforts

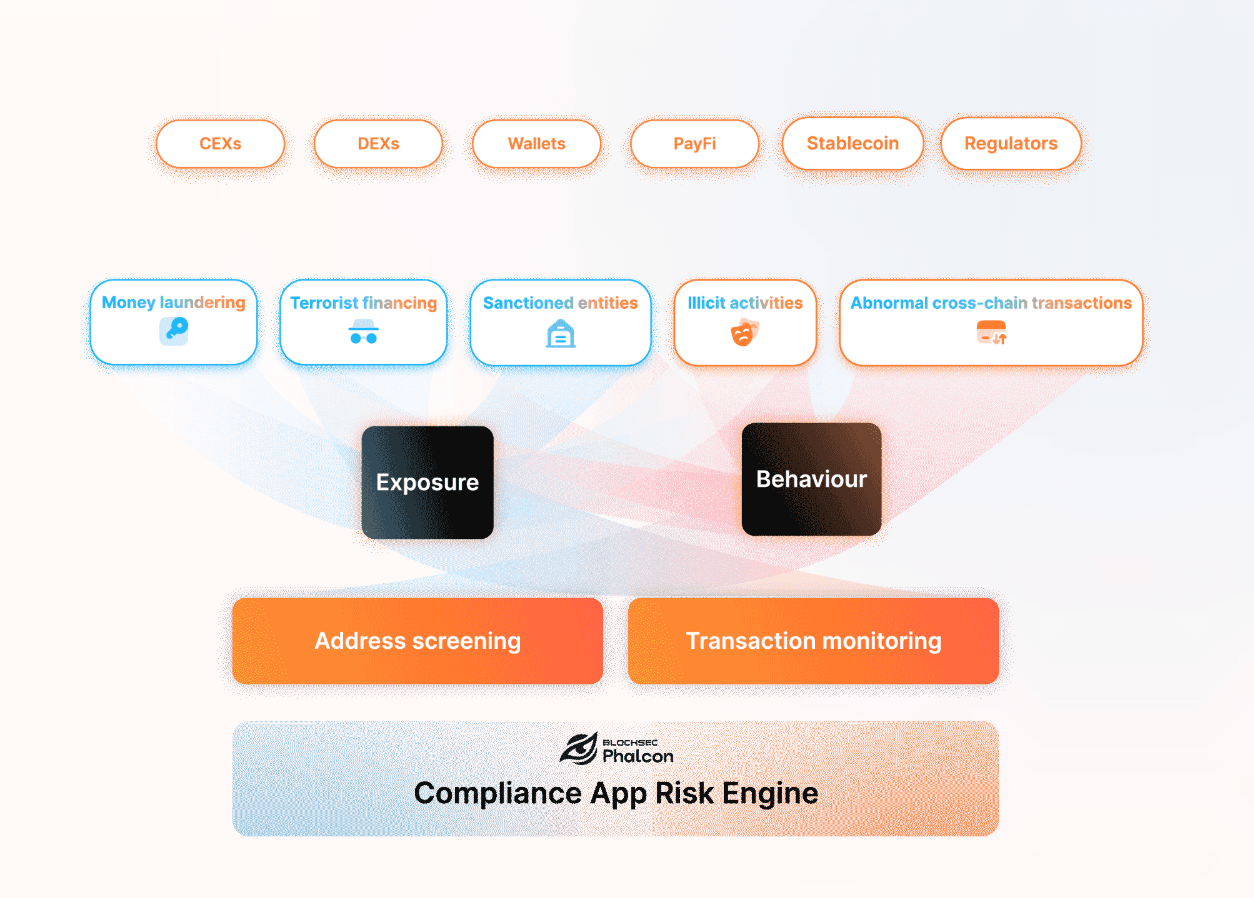

At BlockSec, we are committed to advancing the security and regulatory resilience of the crypto ecosystem. Our efforts in Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Counter-Terrorist Financing (CFT) focus on enabling actionable intelligence, proactive detection, and traceable enforcement mechanisms.

First, our Phalcon Compliance platform is designed to help exchanges, regulators, financial institutions and crypto projects (including crypto payments and DEX) detect suspicious activities in real time. It provides on-chain risk scoring, transaction monitoring, and address screening across multiple chains, helping entities meet compliance requirements.

In parallel, MetaSleuth, our online investigation tool, empowers both analysts and the public to trace illicit fund flows with intuitive visualizations and cross-chain tracking. MetaSleuth has already been adopted by over 100 enforcement and compliance agencies worldwide, including financial regulators, law enforcement, and global consulting firms.

Together, these tools reflect our mission: to bridge the gap between blockchain transparency and regulatory enforcement, while safeguarding the integrity of the decentralized financial system.