Recently, Australia’s Home Affairs Minister Tony Burke officially announced new regulations targeting cryptocurrency ATMs, classifying them as “high-risk products” associated with money laundering, fraud, and child exploitation.

According to Burke, the number of crypto ATMs in Australia has surged from just 23 to over 2,000 in six years. An AUSTRAC investigation revealed that 85% of large transactions conducted via these terminals were linked to scams or illicit activities.

The proposed legislation would empower AUSTRAC to restrict or prohibit high-risk products, explicitly including crypto ATMs. Burke confirmed that the bill will be introduced to Parliament in the coming months.

Meanwhile, on August 4, 2025, the U.S. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued notice FIN-2025-NTC1, warning financial institutions of illegal activity tied to Convertible Virtual Currency kiosks (CVC kiosks) — the technical term for crypto ATMs — and setting clear expectations for Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) and AML compliance obligations.

Meanwhile, on August 4, 2025, the U.S. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued notice FIN-2025-NTC1, warning financial institutions of illegal activity tied to Convertible Virtual Currency kiosks (CVC kiosks) — the technical term for crypto ATMs — and setting clear expectations for Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) and AML compliance obligations.

1. What Are CVC Kiosks?

CVC kiosks function similarly to traditional ATMs, allowing users to buy or sell cryptocurrency with cash. They are often found in convenience stores, gas stations, and shopping areas, and typically support Bitcoin transactions, along with other cryptocurrencies like Litecoin and Ethereum.

CVC kiosks function similarly to traditional ATMs, allowing users to buy or sell cryptocurrency with cash. They are often found in convenience stores, gas stations, and shopping areas, and typically support Bitcoin transactions, along with other cryptocurrencies like Litecoin and Ethereum.

Yet, their risks have become increasingly apparent.

Yet, their risks have become increasingly apparent.

In 2024, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) received over 10,900 complaints related to crypto ATM fraud, with victim losses exceeding $246.7 million — a 99% surge in cases and 31% increase in losses compared to 2023.

The FTC similarly reported an “explosive rise” in scams involving crypto ATMs.

The reasons are clear: once a crypto transfer is executed, it’s nearly irreversible and instantaneous, unlike traditional bank transfers that can take days to settle. This gives victims virtually no time to recover lost funds.

Alarmingly, seniors are the main victims — individuals aged 60+ are three times more likely to fall prey to crypto ATM scams, accounting for two-thirds of all reported losses.

2. Crypto ATMs as Laundering Tools

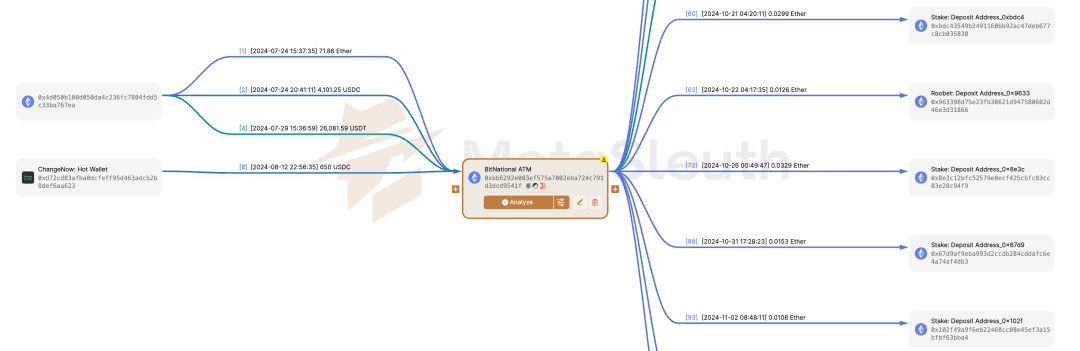

Beyond scams, CVC kiosks have become powerful tools for drug cartels and organized crime.

FinCEN’s analysis of Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) data shows frequent use of kiosks to clean narcotics proceeds. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) further confirmed that transnational crime groups like the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) increasingly rely on CVC for rapid cross-border transfers that bypass traditional cash smuggling risks.

In Illinois, for example, there are 1,626 crypto ATMs, with over 1,100 located in Chicago alone — now a major hub for laundering cartel funds.

DEA investigations found that criminals from other states even travel to Chicago specifically to convert drug money into crypto before sending it overseas.

3. The Compliance Landscape for CVC Operators

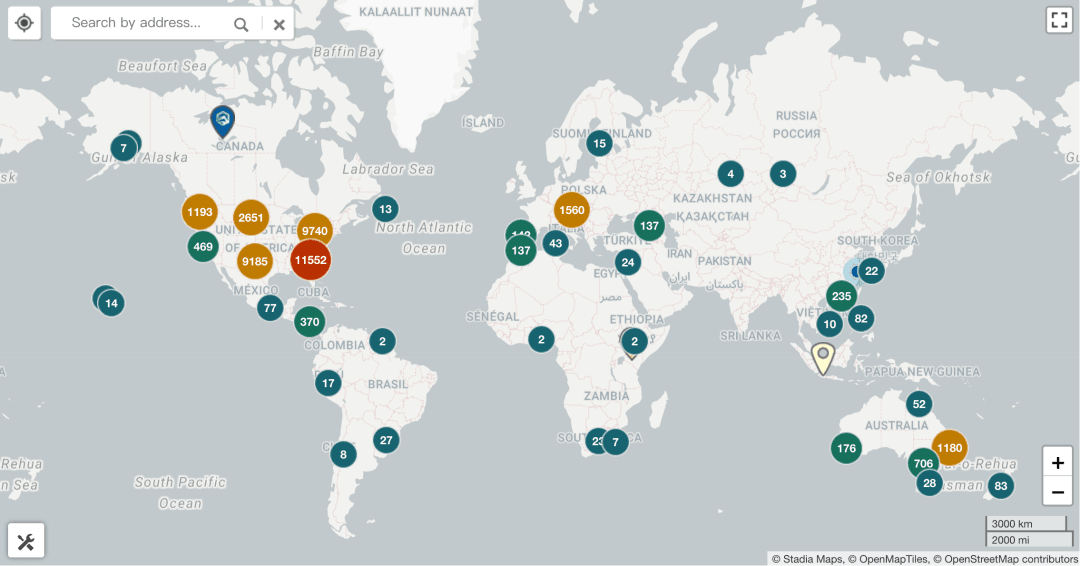

Globally, the number of crypto ATMs has skyrocketed — in the U.S. alone, from 4,128 to 37,342 machines in six years, while Hong Kong SAR has deployed around 224 units, mostly clustered in busy commercial zones like Mong Kok.

However, FinCEN warns that the compliance rate among CVC operators is “alarmingly low.” Many are operating in violation of BSA obligations, dramatically amplifying financial crime risks.

However, FinCEN warns that the compliance rate among CVC operators is “alarmingly low.” Many are operating in violation of BSA obligations, dramatically amplifying financial crime risks.

What legitimate operators must do

Under the BSA, CVC kiosk operators qualify as Money Services Businesses (MSBs) — meaning operating without registration is equivalent to running a bank without a license. Violators face criminal prosecution.

They must:

-

Register with FinCEN within 180 days of launching operations.

-

Report large or suspicious transactions — filing CTR for cash transactions over $10,000 and SAR for suspicious activity exceeding $2,000.

-

Maintain records of customer identification and transaction data for at least 5 years.

States like California have gone further, capping daily transaction limits per customer at 💲1,000. In Iowa, the Attorney General sued two operators whose kiosks facilitated over $20 million in fraud.

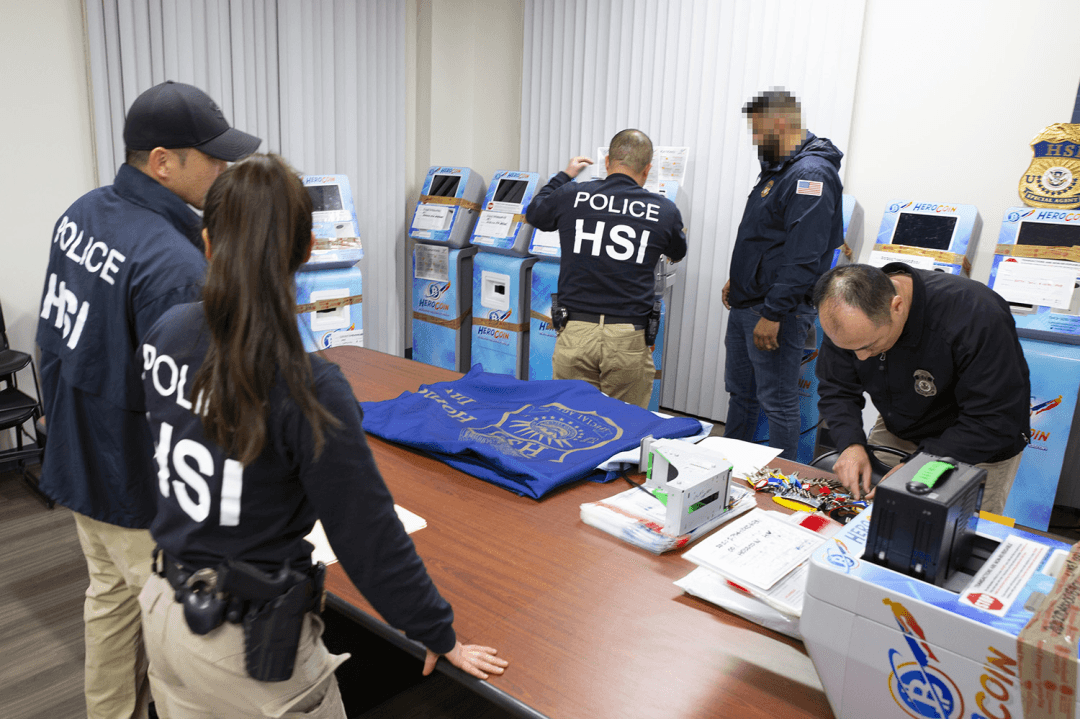

4. Widespread Violations and Enforcement Actions

A 2021 New Jersey investigation found that one-third of operators were unregistered with FinCEN. Others ignored KYC requirements, accepting transactions based on phone numbers or email alone — creating ideal conditions for scammers.

Some even falsified business registrations, used personal or fake company bank accounts, and structured transactions to evade CTR/SAR thresholds, a practice strictly prohibited under federal law.

FinCEN’s notice cites real enforcement examples:

FinCEN’s notice cites real enforcement examples:

-

Orange County Case (2021): Former bank employee Kais Mohammad operated an unregistered ATM network processing over $25 million, failed to implement AML checks, and was sentenced to 24 months in prison.

-

New Hampshire Case (2022): Three operators used fake company accounts for crypto ATM cash deposits and were convicted of wire fraud, facing prison and fines.

Dozens of similar prosecutions have occurred nationwide, with fines reaching millions of dollars and mandatory forfeiture of illegal proceeds.

5. Lessons for the Web3 Industry

While FinCEN and AUSTRAC’s actions appear focused on physical crypto ATMs, they reflect a broader message for the Web3 ecosystem: compliance is not optional — it’s existential.

From scammers exploiting AML gaps to operators facing prosecution, these cases underscore one truth: “Risk knows no boundaries, and compliance leaves no shortcuts.”

The lesson extends beyond ATMs — to exchanges, DeFi protocols, and payment platforms.

As global regulators shift from reactive to proactive enforcement, integrated AML tools like those powering next-generation compliance systems are becoming essential infrastructure for digital finance.

Web3 innovation should never come at the cost of compliance — and this global crackdown proves it.